The following is the second in a two-part series about the York Harbor Poison Pen Scandal. To read the first part,click here.

Allen Ryan was a predatory capitalist to the hilt. Having bought a special police officers’ commission from New York’s police chief, he is credited with having disrupted a planned meeting of “radicals” at Delmonico’s steak house. The Brewster Standard tells us about his commission:

From April 1918, until February 1922, Mr. Ryan served as a special Deputy Police Commissioner, without salary. (He was one of several “millionaires” appointed by Police Commissioner Richard E. Enright.)

Rise and Fall of Allen Ryan

Ryan was at the top of his game in 1918, when he was appointed a police deputy, but two years later his good fortune crumbled.

Ryan was brought to grief by the iconic Stutz automobile brand. He had tried to corner the market on Stutz shares. The scheme failed, and by 1920, bankers took control of his assets when his father refused to bail him out.

Forbes Magazine tells us,

Most fathers half as rich as Thomas Fortune Ryan would have rescued their sons from such financial disgrace. But the older Ryan has always had the reputation of being a greedy, grasping, scheming mercenary. Moreover, when the father remarried almost before his wife’s body was cold, Allen publicly denounced his father.

Critics blamed his early success for his demise:

…young Ryan became puffed with the delusion that he was an industrial and financial Napoleon. Early success inflamed him into recklessness. He launched project after project. During the universal boom some of his ventures were carried along. But, like too many others, young Ryan paid more attention to the stock ticker than to the prosaic running of factories. Wall Street rang with sensational tales of his speculative exploits. His stock market winnings were estimated at millions. (Forbes, Vols. 10-11)…

York Harbor Assets

Ryan managed to hold on to some of his assets, including his home in the Norwood Farms section of York Harbor. Now people know it as Stage Neck.

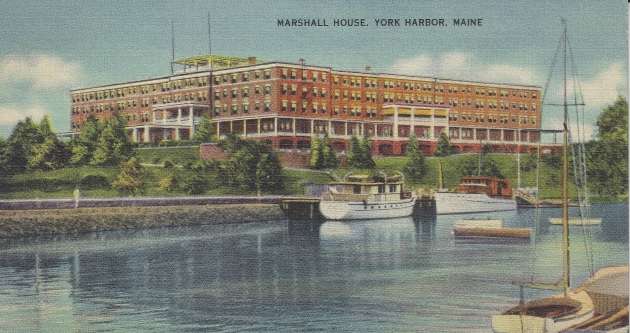

York Harbor back in Ryan’s day has been described as “a first-class summer emporium for wealthy tourists.” on a par with Bar Harbor and Newport. The town was famous for its exclusive Gilded-Age properties like the Marshall House, symphony ensembles and costume balls for the summering rich. It also offered genteel attractions like the Reading Room and Cliff Walk.

Unlike its more hurly-burly neighbor York Beach – home to such middle class entertainments as Goldenrod Kisses, the sands (both Long and Short) and the Cape Neddick Light—the Harbor was summer home to people who considered themselves of the highest class. They liked to let others know it.

Jewel Theft

In 1922, the Ryans were the victims of a robbery in Maine. On the night of August 8, someone entered and left Sarah Tuck Ryan’s Norwood Farms bedroom by a window. The burglar stole $15,000 worth of jewelry, including bracelets, rings, watches and lavalieres. That began a crime wave in York Harbor that summer. The New York Times reported,

Mrs. L.R. Page of Philadelphia … lost a diamond bracelet. Others robbed were H.B. Dominick of New York, who lost a watch and rings worth $3,000, and C.E. Curtis of New York and his daughter Elizabeth, also lost $4,000 worth of jewelry.

At the time, Sarah Tuck Ryan suggested that taxi drivers familiar with her luggage had committed the crime. Police later came up with another theory. They said one man had committed those burglaries (except for Mrs. Page, who lost her bracelet in the Reading Room). And they hinted to the press the identity of that man: ASCAP President George Maxwell, the central figure in our ‘Poison Pen’ scandal.

In the summer of 1922, Maxwell arrived in York Harbor toward the end of July and stayed at the Marshall House for a week. Then he moved to “Happy” Hunter’s cottage on the harbor. Police said he associated with many prominent people during his stay.

George Maxwell

But it wasn’t until the next year that Maxwell’s name would explode in the international press, linked in the most sordid way with Sarah Tuck Ryan and a host of other women. They included a Danish opera singer, a concert singer, a ballet dancer and a motion picture actress, with whom he was alleged to have toured Mexico.

That Sarah Tuck Ryan would get involved with both Allen Ryan and George Maxwell seems far-fetched. Allen Ryan was the apotheosis of the financial speculator. George Maxwell, on the other hand, believed men should get fairly paid for their actual work – then an uncommon point of view on Wall Street.

Maxwell’s founding of ASCAP started with a 1910 New York visit by the great opera composer Giacomo Puccini. Maxwell then represented the Italian company Ricordi, which published Puccini’s works. Puccini asked Maxwell why he didn’t get paid for his melodies, which he heard in restaurants and hotels. According to Broadway: Its History, People, and Places : An Encyclopedia,

Puccini had good grounds for his argument. The United States copyright law of 1909 guaranteed the owners of musical copyrights the exclusive right “to perform the copyrighted work publicly for profit if it be a musical composition.”

Giacomo Puccine

From this was born ASCAP, which functioned as a sort of collection agency for artists, tracking down and recovering payments for their work when it was used improperly.

York Harbor

Twelve years later, Sarah Tuck Ryan would find herself involved with both George Maxwell and Allen Ryen. She was married to Ryan—though it was a rocky marriage that endured at least one separation.

Her affair with Maxwell supposedly began shortly after April 6, 1922, when she sailed for Europe on the Mauretania with Mrs. Huhn of Park Avenue. She met Maxwell on board and the two became infatuated with each other, according to a later account in the Lewiston Daily Sun that described him as a “gay Lothario.”

Mrs. Ryan and Maxwell stayed in London and Paris together, and took a trip to Lake Como and Milan. Whenever they were separated, they exchanged letters. On June 6, she returned to New York on board the steamship Majestic, exchanging radiograms with Maxwell every day. Their frequent exchange of letters and radiograms over the course of their year-long affair would later titillate the public. One such overheated radiogram from Sarah Tuck Ryan read,

I am counting the hours. I will be there to meet you in Paris. Love, only love. Love of life.

Later in the summer of 1922, she took her family to York Harbor. Maxwell returned to the U.S. on June 14 and took two trips to visit her in York Harbor – the time frame of the jewel thefts.

The Trouble Begins

On Oct. 7, Sarah Ryan left on a steamship with her five youngest children to Paris. As had become their practice, she and Maxwell exchanged radiograms daily on her crossing. When she landed in Europe she exchanged three or four cablegrams a week. On March 7, 1923, Maxwell sailed for Paris to join her. Three days later, the trouble began.

Allen Ryan received a poison pen letter that said Maxwell and his wife Sarah were having an affair. He immediately hired a detective to travel to France and investigate.

The detective found photos of Sarah Tuck Ryan and her clothing in Maxwell’s apartment. He questioned Maxwell about those and about the letter. Maxwell denied everything. He produced a similar “poison pen” letter that he, too, received.

Allen Ryan didn’t believe it. He believed that Maxwell himself sent the letter as a way to break off the affair with his wife. Ryan turned the evidence over to New York prosecutors, who began their own investigation. Ultimately, they found that as many as 135 poison pen letters had been written to the husbands of 40 other East Coast socialites with whom Maxwell had allegedly been sleeping.

New York’s district attorney indicted Maxwell for forgery and for “sending scurrilous and obscene letters through the mail.” The forgery charge claimed he had put the names of fellow members of the New York Yacht Club on the return address of his poison pen letters.

Maxwell denied the elaborate scheme. He was being framed, he argued, by someone trying to discredit him. He had his share of enemies as a pioneer of ASCAP, the system that was forcing theaters, music halls and others to start paying royalties for music and artistic works that they had previously reused for nothing.

Return to York Harbor

In July of 1923, news of Maxwell’s indictment broke, and it found a particularly welcoming audience in Maine. The ASCAP “Lothario” and his trips to Maine to visit Mrs. Ryan made headline news. Mrs. Ryan was, at the time, aboard a steamer returning from Europe to America. Maxwell remained in London, as Allen Ryan demanded his extradition.

News continued to drip out about the New York proceedings. It included quotations from transatlantic cables – the text messaging of its day—between Mrs. Ryan and Maxwell. The missives seemed suggestive and possibly contained code words. Police revisited the York Harbor jewel thefts of the summer before, noting that two of the victims’ husbands had received poison pen letters. They were Sarah Ryan, of course, and Mrs. Louis R. Page.

Then another woman was named in the scandal: Beatrice Gallatin. By then, society-watchers eagerly scanned the news for the release of more names. They would be disappointed.

Mrs. Gallatin, perhaps aided by a New York society ready for a quick end to the scandal before more names were drawn in, told a judge that the allegations were incorrect. She publicly defended Maxwell. Before Maxwell returned to New York to face the charges, a judge dismissed them.

Late in July, Mrs. Ryan returned to the states and took refuge deeper into Maine, hiding out at a camp in Casco. Her physician reported that she was in hysterics over the whole affair. The county sheriff pledged to run off any curious trespassers who bothered her. Allen Ryan, citing his conversion to Catholicism, said he and his wife would not divorce. The case against Maxwell got a bit more tractions, with questions arising about the legality of the search of his property. The story largely fell from view, however, as just one more summer entertainment.

Post Mortem

George Maxwell continued to run ASCAP and the organization prospered. It is one of the largest performing rights organizations in the world, collecting royalties for musicians and artists. Its annual revenues are nearly $1 billion.

In the unwinding of Allen Ryan’s finances, Stutz Motor Car eventually passed into the hands of a group of investors that included, most prominently, Ryan’s friend Charles Schwab.

The Ryans themselves, despite Allen’s protestations, got divorced in 1924. This time Sarah named a co-respondent, and Allen denied any wrongdoing. Allen Ryan remarried the following year, but never returned to prominence on Wall Street. He died in 1960.

When Allen Ryan’s father died in 1928, he left his son nothing but one pair of pearl shirt studs. Ryan’s siblings agreed to provide him with greater compensation in return for his not suing.

This story last updated in 2022.