In the history of New Hampshire, Austin Corbin stands out as probably the most loathsome blight the state ever produced.

So perhaps it’s fitting that his Newport mansion sold in 2019 for a fraction of the asking price. Corbin built the estate around his childhood home, which he razed except for his old bedroom. The house measures 7,500 square feet with four bedrooms and six bathrooms, and the owners asked $3.75 million for it. In September 2019 it sold for $612,733.

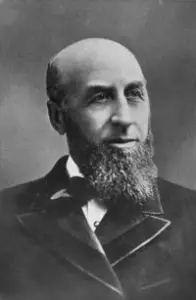

Born on July 11, 1827, Austin Corbin made his mark on the world as a railroad man, plantation owner, resort operator and banker. His success came mostly in places outside New England, such as Arkansas, Iowa and New York. And he carefully cultivated the image of a prosperous businessman who summered at his New Hampshire mansion.

A Monument to Greed

The mansion was his birthplace, but he gradually tore it down over the years. In its place he erected a monument to his greed, complete with a private rail siding for his personal rail cars. You can see it here as it was when the Wall Street Journal featured it as the House of the Day in 2012.

Austin Corbin continued visiting New Hampshire his whole life, and died on his estate in 1896. He was much lamented by the press of the day, which regurgitated the pleasant fiction of the self-made business success.

Scratch the surface of Corbin, however, and you unearth a long and sordid history of corruption, swindling, bribery, thuggery and anti-Semitism. It’s hard to imagine that one man could possess all these traits and in such full measure — but he did.

Austin Corbin

Austin Corbin is largely forgotten in New Hampshire now, but one odd memorial to him remains: Corbin’s Park. You’d need to look a little bit to find it. Even if you did you couldn’t get in (because it’s fenced off and private). But it still exists, taking up 20,000-plus acres – roughly half the size of Lake Winnipesaukee. You’ll find it in Sullivan County near Claremont on the borders of Grantham, Croydon, Cornish and Plainfield.

The park was odd even when it was conceived in 1888, and it’s odder still today. Once upon a time it was open to public visitors; it now remains silent for most of the year. It serves only as a local curiosity and private animal preserve for canned hunts. It’s made the news in the last 20 years only once — when a hunter mistook one of his companions for one of the park’s boars, shot at him (twice) and killed him.

Still, Austin Corbin and his park remain a subject of interest. Brian Meyette, a neighbor of the park, has created an authoritative and informative history of the park at his website. He writes on the site, and rarely does a day go by, even now, when someone doesn’t land on the site looking for information.

Widely Despised

And if you read about the robber barons who did so much to crash financial markets and corrupt governments in the 1800s, you’ll find Austin Corbin generally makes an appearance. In the photo below from the satirical magazine Puck from September 1882, Austin Corbin is depicted in a Louis XV-style party cavorting with other unscrupulous businessmen of his ilk, such as Jay Gould and Russell Sage. A host of senators, including Massachusetts’ George Hoar, are dressed as their courtesans. Corbin stands to the rear of the group with his back to us and a bag of money slung over his shoulder.

Though not as prominent as some of the wealthier robber barons, Austin Corbin was well-known and widely despised in his day. And the story of that black hole of forest in the middle of New Hampshire and the man who created it provides some stunning parallels to the corruption we are surrounded by Austin today.

Friends in High Places

Austin Corbin’s business success is indisputable. He made a long career out of marrying his political connections with his business interests to his benefit and the to benefit of his investors. After learning law at Harvard Law School, he went to work with Ralph Metcalf, Newport’s politically connected lawyer and former New Hampshire secretary of state. Metcalf would later go on to serve two terms as New Hampshire governor.

In 1851, Austin Corbin struck out for the western frontier, which at the time was Iowa. He was armed with his and Metcalf’s connections and investor cash. Metcalf alone had loaned him $1,200. Arriving in Davenport, Iowa, he began working as a lawyer. However, he quickly jumped into the more lucrative real estate and banking trades. Here he got his first experience in the profitable business of selling mortgages to the flood of people relocating to the Midwest.

Banking in mid-1800s was a state-by-state business, with banks each issuing their own currencies supported by their gold reserves and their own credit from lenders. The system was unstable, open to a host of threats such as banks overextending themselves and counterfeiting. The result was a system where anyone accepting currency had to question first if it was real and, if so, was it actually worth anything?

Banking on Success

Austin Corbin succeeded in this rough-and-tumble business. He ran one of the few banking concerns in Davenport that did not have to shut its doors during the 1857 financial panic. However, he was also intimately familiar with the weaknesses of state-by-state banking. At one point, he and his banking partner caused a minor panic in Davenport when they began refusing Illinois currency because of their suspicions about its soundness.

Such decisions were difficult. Accept a weak currency and a bank could be out a lot of money. Refuse it and its customers would revolt. When the Congress passed the National Banking and Currency Act of 1863, Austin Corbin and a group of associates received the first charter for the First National Bank of Davenport. It was the first national bank anywhere under the new rules, according to the bank’s published history.

The national bank system and uniform currency were highly unpopular with established banks. They were accustomed to making money off their own currencies. But the politicians of the day desperately needed to stabilize the financial markets and gain a new source of revenue for the fast-accumulating Civil War debt. The national banks, operated by the Republican-friendly businessmen who won their charters, would provide a much-needed supply of customers for that debt.

Austin Corbin, always politically plugged in, saw the opportunity. He and his colleagues in the First National Bank of Davenport wasted no time in sending off their application to Washington, D.C., seeking the charter. In addition to his political insights, Corbin also had another asset that may have helped clear the way for his banking venture. President Lincoln’s Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase.

Another Friend

Chase, who wrote the National Banking and Currency Act and issued the charters, was also a fellow son of New Hampshire. Originally from Cornish, Chase had moved to Cincinnatti, Ohio, in the 1830s. The he won election as both senator and governor before Lincoln chose him as his treasury secretary. He was also Austin Corbin’s cousin.

No strong record details the relationship between Corbin and Chase, who sought the presidency three times and failed at each attempt. On at least one occasion, however, Corbin repaid the kindness of his cousin. Chase’s daughter had married the governor of Rhode Island and the two had a turbulent and scandalous marriage with infidelity on both sides. On one well-documented occasion, Chase’s daughter was driven from their Rhode Island mansion. Corbin gave her shelter and, more importantly, stepped forward to defend her in the press.

For two years Corbin acted as the Iowa bank’s president, and when he resigned in 1865 the bank’s assets had grown from $100,000 to more than $500,000. The national charter had been a goldmine for those banks that seized the opportunity. With their single, uniform currency they were wildly popular with the stability-seeking public. Local currencies, soon subject to discounts by anyone accepting them, gradually left circulation.

The future for the national banks looked bright, but Austin Corbin decided his interests would be better served in New York. And so he took his now-considerable fortune to Manhattan where he could profit by connecting eastern capital with western farmers.

Friend to the Farmer

Corbin’s devious brain saw an opportunity in the rewritten banking act. Congress had restricted commercial banks from holding mortgages. While this protected the currency from being tied to institutions conducting profligate lending, it also created a business opportunity for Corbin. He worked with mortgage companies and a network of brokers to sell mortgages to farmers in the frontier states. The mortgages would be profitable enough, paying 7 to 10 percent. Austin Corbin,though, found a way to improve on that.

His mortgage brokers also kept a portion of the loan as a fee. For instance, someone borrowing $1000 would pay the regular payments with 10 percent interest to Corbin’s mortgage company until the $1000 was repaid. In addition, the borrower would pay a fee to the broker of perhaps $200 from the loan itself.

Corbin’s practices were illegal. He was sued and convicted of usury for the scam, but he succeeded in hoodwinking the farmers more often than he got caught. He became a millionaire in the process and earned his investors far more of a return.

Still, to any ambitious, flimflam man of the era, mortgage scams amounted to small potatoes. The mortgage processing machinery that Wall Street used to destroy the economy in 2008 hadn’t been invented yet. In Corbin’s day, the real action was in railroads, and that’s where he focused his energy.

Railroads

Railroads in the late 1800s were booming. There was no quicker, nor more corrupt, way to make big money fast. States, counties and municipal governments would grant millions of acres to the roads to lure them in. Financing was readily available for the sexiest venture of the age. And the western frontiers had a tremendous appetite for moving freight and goods.

In addition, the constant mergers and the possibilities for fraud and speculation were tailor made for the Wall Street hustlers. Some of America’s biggest fortunes were made, at least in part, off the railroads. Vanderbilt, Gould, Corning, Harriman and Fisk all profited mightily off the boom, and Austin Corbin intended to join the party.

He is described as a reluctant participant in his first venture — bringing the Indiana, Bloomington, and Western Railroad out of receivership as its president. Corbin quickly saw how the industry worked. The I.B.&W was born out of the financial mismanagement and corruption of the smaller lines brought together to form it. It connected Indianapolis with points in Illinois.

After Austin Corbin shepherded the railroad from receivership in 1870, it racked up a remarkable $13 million in new debt. Then it collapsed into default again in July of 1874. Furious bondholders were left picking through the ashes of the company that now consisted of an inventory of decrepit equipment and little cash. The books were a tangle of self-dealing, and there was little to recover. It gave Austin Corbin a taste for what railroading could be, though, and he went on to own or control numerous railroads in his lifetime.

Philadelphia and Reading

Compared to Frank Gowen, Austin Corbin was a saint. But that’s not saying much. Gowen assumed the presidency of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad in 1870, at the age of 33. The Reading had a profitable business in transporting anthracite coal from the Schuylkill County region of Pennsylvania to Philadelphia. There it could be loaded out to other destinations.

Cowen believed that Reading could enhance its profit if it could also own the coal mine and the ships that carried it. The Reading’s charter, however, prevented it from engaging in mining. So one of Gowen’s first acts as president was to convince the Pennsylvania Legislature to create a special entity that would be formed to develop coal in the Schuylkill region. Its stock would be available for purchase.

No sooner did the law pass than the Reading Railroad began buying the stock and pouring its money into the region’s mines. Eventually, the Reading would be the major coal operation in Schuylkill, operating as the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company.

The coal miners’ lives were a bitter struggle. The pay was low and the work extremely dangerous. A quarter of the workers were children between 7 and 16. The Irish immigrant miners had formed the Molly Maguires, who used guerilla tactics against the mine owners.

Molly Maguires

When Gowen took control of the Reading in 1870, it was at the heart of the Molly Maguires disputes that had rocked the region since 1833. Gowen decided to escalate. He reduced wages for his workers, guaranteeing a high level of violence in the region. He hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to infiltrate the group. The Pinkertons passed along information to vigilantes who murdered the Maguires and their families if the state couldn’t execute them legally.

Throughout the period, the railroads and mines persistently sought to lower wages. All the while the railroad executives traveled the rails in luxurious private rail cars and vacationed abroad. The excess and inequality frequently caused strikes. No sooner would one strike end then the companies would cut wages and prompt another strike. One particularly long strike in 1877 included a massacre of railroad men in Reading.

Throughout the chaos, the Reading held a virtual monopoly on anthracite coal. During this period it used dubious means to make money: It fixed prices with other mines, delayed and limited shipments from competitors that would not cooperate, and manipulated its stock both up and down. One of the company’s clever tricks was to charge exorbitant shipping fees to the mining company that it owned to carry its coal. The mining company would borrow the millions to pay the fees, and then the railroad would record the loan proceeds as revenue even though it would need to repay the loans.

Gowen took the company into bankruptcy twice, and after 10 years he began losing his grasp on it. J.P. Morgan finally ousted him. In 1887, with the railroad in receivership, Morgan created a trust to run it with Austin Corbin as president. Corbin reorganized the line to much fanfare, but his tenure would not last long.

Hiring Scabs

Virtually his first act as president was to reignite old fights with the miners, and he managed to extend the fight to the more reserved railroad engineers. From December 1887 to April, 1888, the Reading was beset with strikes. Corbin managed to bring in strikebreakers.

Congress hauled him to Washington to face charges that he provoked a strike by lying that he would raise wages. That let him push coal prices higher and hire scabs at lower wages. Congress exposed the Reading’s fiddling of its books and rigging of coal prices. The company subsequently took a beating in the press.

Austin Corbin also infuriated the congressional committee members by offering to take them to Reading in a posh, private rail car. In that era, people viewed such blatant efforts at bribery as at least somewhat shameful.

People who worked for a living viewed Austin Corbin with derision. The Locomotive Firemen’s Magazine, for example, published an article about the strike. In it, Austin Corbin was described as belonging to ‘that tribe of human monsters who prey upon poor men, who combine the natures of hog and shark, who, being influenced by greed, make war upon the weak, regardless of right.’

For Austin Corbin, however, criticism from his own kind caused greater problems. While Morgan had cleared out the competition for the Reading once, the remnants of the old management weren’t entirely silenced. The trust had control, but the stockholders were still eager to play games with the company.

Critics

Corbin’s critics constantly needled him. They accused him, for instance, of filling coal cars and putting them on sidings. That way he drove up coal prices by preventing competitors from using them to ship coal. And his critics damaged him seriously when they uncovered another example of his self-dealing.

As the Reading struggled, it could not maintain lease payments to a New Jersey railroad over which it shipped coal. That resulted in a loss to the Reading and a gain to the New Jersey line. Using this information, Corbin heavily invested in the New Jersey rail line.

This kind of manipulation was commonplace among railroad barons, but it resonated with investors who perceived management was more interested in personal profit than the operations of the company.

Austin Corbin beat back his critics, and shareholders selected him to continue on as president. But in 1890 he did an about-face and resigned. It’s unclear why. Did he face new allegations? Had Morgan lost faith in him? Or had he simply realized the company was headed for disaster once again? Because in 1893 the Reading again defaulted.

This time, it signaled the start of the nationwide depression of 1893, which brought years of hardship for the country.

It would be impossible to catalog or reconstruct all of Corbin’s railroading schemes. However, in part two of this article we look at some of his other ventures.

8 comments

[…] The Robber Baron of New Hampshire – ‘Part hog, part shark’ […]

[…] Sprague did divorce. After the disruption at Narragansett Pier, Kate turned to her distant cousin Austin Corbin, a railroad tycoon. He let her stay at his Long Island estate, protected by […]

[…] tradition provide rich material for stories and characters set against quaint fishing villages, Gilded Age resorts and prep school […]

[…] drew up the guest list from the who’s who of young society – the desultory offspring of the robber barons and impresarios of the gilded […]

[…] rich material for stories and characters set against quaint fishing villages, gritty mill cities, Gilded Age resorts and Ivy League […]

Wasn’t the name on Monopoly the Reading Railroad?

[…] New England Historical Society magazine has an article about Austin Corbin, the man who created the playground for gun-toting millionaires in the late […]

[…] New England Historical Society wrote about Austin Corbin, who founded the park. The article calls him a ‘part-hog, part-shark’ robber baron: Read it here. […]

Comments are closed.