Charles Ives never forgot the sights and sounds of the village cornet band marching to the cemetery in Danbury, Conn., on Decoration Day. His father, George Ives, had served as a bandmaster in the Union Army and led the town bands after the Civil War.

Charles was born in 1874, soon enough after the war to understand the pain and loss the town still felt. He lived a typical life for a boy from a prominent old New England family. He starred on the baseball diamond, graduated from Yale, married, played the organ in church on Sunday and got rich on Wall Street.

But he led an unconventional life at night and on weekends. Charles Ives composed avant-garde orchestral music, much of which evoked the memories of his boyhood. He revived those early Decoration Days in the second movement of his symphony, New England Holidays, which also included Washington’s Birthday, Fourth of July and Thanksgiving.

Ives’ colleagues knew him as a successful insurance man and were surprised to learn he composed music. No one performed his orchestral music until late in his life. He didn’t care; he wrote what he wanted to write without worrying what his listeners thought. His compositions had dissonance and complexity, wild noises and what conductor Michael Tilson Thomas called ‘confrontational crunches.’

Charles Ives’ Decoration Day

He worked on New England Holidays for years, even decades for the last movement, Thanksgiving.

Ives used hymns, folk songs, marching bands, country fiddlers, a blacksmith’s hammer, church bells and fireworks to paint a musical picture of perfect childhood days. In Decoration Day he evokes the overgrown lilacs in front of the homes abandoned by Civil War soldiers and the sounds of the cornet band. Ives explained what he was getting at with Decoration Day in a written preface to the musical score:

[1]In the early morning the gardens and woods about the village are the meeting places of those who, with tender memories and devoted hand, gather the flowers for the Day’s Memorial…

[2]After the Town Hall is filled with the spring’s harvest of lilacs, daisies and peonies, the parade s slowly formed on Main Street. First came the three Marshalls on Plough horses (going sideways); then the Warden and Burgesses in carriages, the Village Cornet Band, the G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic) two by two, the Militia…the inevitable swarm of small boys following.

[3] The march to Wooster Cemetery is a thing a boy never forgets. The roll of muffled drums and “Adeste Fidelis” answer for the dirge. A little girl on the fence post waves to her father and wonders if he looked like that at Gettysburg.

[4] After the last grave is decorated, “Taps” sound out through the pines and hickories, while a last hymn is sung.

[5] When the ranks are formed again and “We all march back to Town” to a Yankee stimulant–Reeves’ inspiring “Second Regiment Quick-Step” — though to many a soldier, the somber thoughts of the day, underlie the tunes of the band.

[6] The march stops — and in the silence, the shadow of the early morning flower-song rises over the Town and the sunset behind West Mountain breathes its benediction upon the Day.”

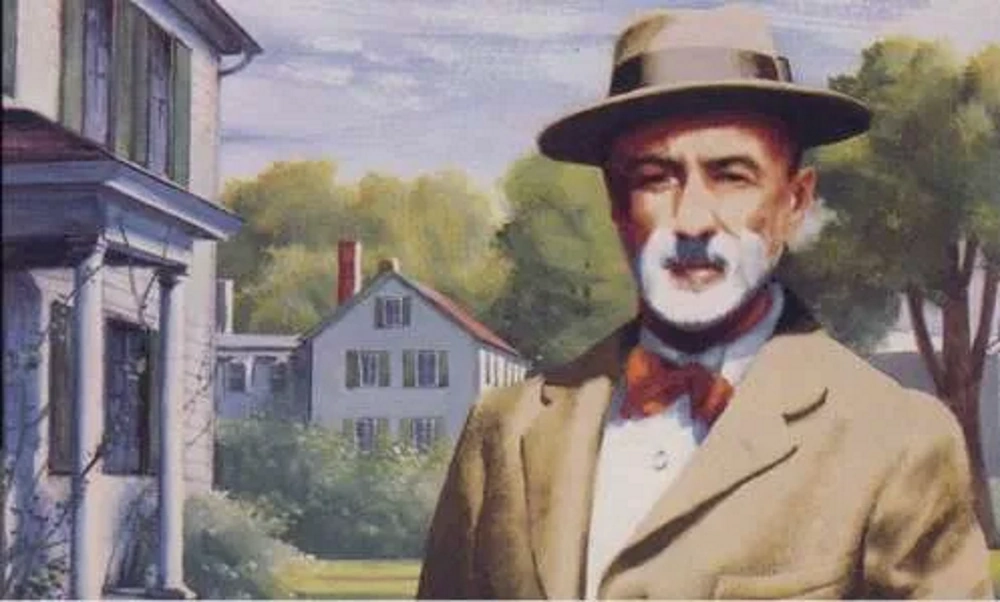

Charles Ives

Charles Ives was born to a prominent Danbury family on Oct. 20, 1874. His family home, built in 1780, held several generations of Iveses. George Ives, his father, helped found the Savings Bank of Danbury and the Danbury and Norwalk Railroad, now a branch of Metro-North’s New Haven Line.

Charles played drums in his father’s marching band in Danbury. George liked to experiment with music. He used to direct two bands to march toward each other playing different songs. He also made his son sing well-known songs while he played something different in a different key. Those experiments would appear later in the work of Charles Ives.

A Conventional Life

His father’s unconventional approach to music were perhaps the only indication Charles Ives would become a path-breaking composer of music. His life did not defy convention.

He composed Symphony No. 1 for his senior thesis at Yale, but his advisor’s reaction convinced him he couldn’t make a living writing the kind of music he wanted to. So he went to work for an insurance company, and eventually founded a successful insurance agency. In 1908, he married Harmony Twichell, whose father had a close friendship with Mark Twain.

His choice of a wife with the first name Harmony seems especially apt. So is the fact that she presided as president of the Mark Twain Society. Ives championed ordinary people over elites in his music, in his memory and in his politics.

He once proposed a Constitutional amendment that would allow citizens to propose bills in Congress. Each year, Congress would pick 10 proposals and put them to a national ballot referendum. Ives printed a pamphlet about the plan and sent it to the 1920 Republican National Convention, but it arrived too late.

By then, Charles Ives had already had his first heart attack during World War I. An argument with Franklin D. Roosevelt, then assistant secretary of the navy, triggered the attack. Ives had suggested financing the war effort with war bonds as low as $50. Roosevelt “scorned the idea of anything so useless as a $50 bond,” but later came around to the idea.

Musical Legacy

He bought a camp in Redding, Conn., which he eventually expanded into a home and studio. There he could retreat for the weekends composing his music, which he didn’t expect to be played in public.

Ives composed prolifically, especially from 1907-1918. Then one day in 1927 he came downstairs with tears in his eyes and told Harmony he couldn’t write music anymore. “It just doesn’t sound right,” he told her. He continued to revise his music, however. He worked on Thanksgiving, the final movement of New England Holidays, for 30 years.

Ives also secretly financed the careers of up-and-coming composers as Lou Harrison and Nicolas Slonimsky. In 1931 and 1932, Slominsky conducted the first three movements of New England Holidays.

In 1947, Charles Ives won the Pulitzer Prize for his Symphony No. 3, The Camp Meeting. He didn’t care, calling prizes ‘badges of mediocrity.’ He gave away his prize money, saying, “Prizes are for boys and I’m a grown-up person.”

Leonard Bernstein, who called Ives the greatest American composer, premiered Ives’ Symphony No. 2 in 1951. Ives heard it over the radio.

Ives moved around, but often returned to his family home for gatherings. As Danbury grew from a town to a city, commercial buildings and their clutter grew around the Ives house. The Danbury Museum and Historical Society now owns the house, which it is trying to restore as a museum.

Charles Ives died on May 19, 1954.

To see a documentary about Charles Ives and New England Holidays, click here. With thanks to Music of the First World War by Don Tyler

Album cover of Charles Ives, CC by 2.0. Charles Ives’ house By Daniel Case – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11377562. This story last updated in 2022.