Eli Terry masterminded many of the time pieces that exist today, and in the process he helped ignite America’s industrial revolution.

![]() His legacy can likely be seen in clocks on the walls of your home, office, school or workplace. Some were undoubtedly produced by TIMEX, Seth Thomas or other Connecticut clock makers.

His legacy can likely be seen in clocks on the walls of your home, office, school or workplace. Some were undoubtedly produced by TIMEX, Seth Thomas or other Connecticut clock makers.

It was Eli Terry who started the massive clock-making industry that once thrived in Connecticut cities and small towns.

He taught the art of clock making to other master clock makers like Seth Thomas and Chauncey Jerome. Jerome brought mass manufacturing to Bristol, making 200,000 clocks a year in the 1840 – and making Bristol the clock making capitol of the world. Jerome’s firm also started the Waterbury Clock Company, which later formed TIMEX.

And yet Eli Terry was once mocked as a foolish man with improbable ambition.

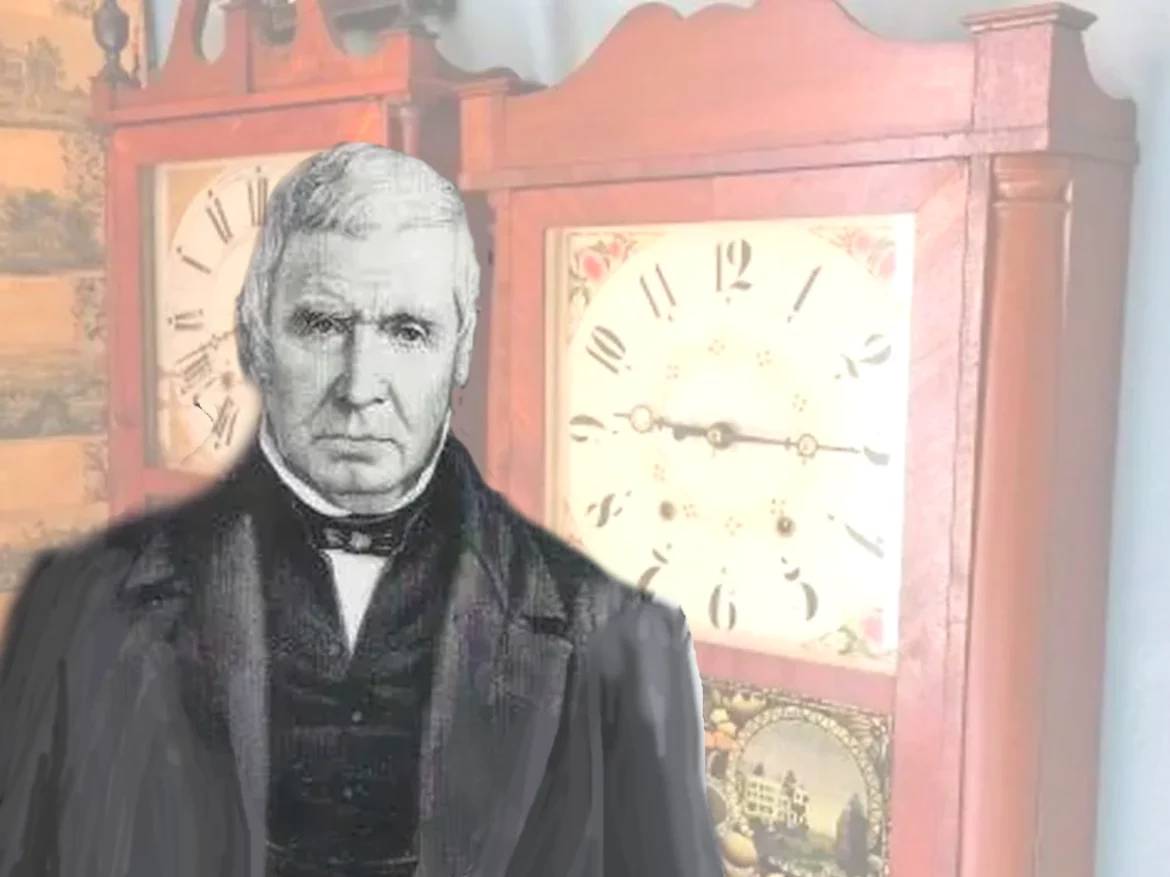

Eli Terry

Eli Terry was born in East Windsor, Conn., on April 13, 1772 to Huldah and Samuel Terry. Terry learned clock making from Daniel Burnap (1759-1838), who was also a goldsmith and watch repairman. Burnap learned clock making from Thomas Harland, an Englishman.

In 1786, Eli Terry started his six-year apprenticeship with Burnap, engraving brass clock faces and working on movements.

After his apprenticeship ended, Eli Terry moved to Northbury, Conn., in 1793. He married Eunice Warner (1773-1839) and purchased land from her father where he built his house, which still stands today. His first clock shop was a 20-foot square workspace on Niagara Brook, which flows just behind the house. It was the first water-powered clock factory in the United States. Northbury split from Watertown to form the Town of Plymouth in 1795.

Before Terry moved to Plymouth, he made typical eight-day brass tall case clocks, or what we call grandfather clocks today. At this time, clock makers in the area began producing wooden gear clocks instead of brass gear clocks. These primitive clocks were made of local wood and cut out with a simple saw or knife. Wooden clocks were far more affordable than any brass clock.

In 1795 Eli Terry began to make 200 clocks at the same time. Back then, it would take about a month to make a brass gear clock and over a week to make a wooden gear clock. Terry dreamed of making affordable clocks so that any family, rich or poor, could have a timepiece in their home.

Wooden gear clocks at the time were not really intended to last more than about 20 years. Eli Terry’s wooden gear clocks are still keeping perfect time today over 200 years later in the homes of clock collectors, museums, and whomever is fortunate enough to possess one of these master timepieces.

Foolish Man

Chauncey Jerome once recalled a conversation his guardian had with some friends, mocking Terry. Jerome, quoting the conversation, wrote in 1860: “The foolish man had begun to make 200 clocks; one said, he never would live long enough to finish them; and another remarked, that if he did he never would, nor could possibly sell so many, and ridiculed the very idea.”

Terry easily finished those clocks and his business flourished. In 1806 Terry purchased an old gristmill owned by Calvin Hoadley in southern Plymouth. Here he hired two joiners, Silas Hoadley (1786-1870) and the infamous Seth Thomas (1785-1859), to operate his new factory.

The Porter Contract

In 1807 Terry entered into a contract with Edward and Levi Porter of Waterbury, Conn., to make 4,000 clocks in three years. Terry spent the first year planning and building the machinery. The second year he produced the first thousand clocks. The third year he produced the remaining 3,000 clocks.

Terry used interchangeable parts in his clock factory. Clock gears were made as many as a dozen at a time, and women were hired to paint the clock faces. Terry’s Porter Contract was one of the key kickoffs to the American Industrial Revolution.

Terry sold his Porter Contract factory to Silas Hoadley and Seth Thomas in 1810 and moved to the Naugatuck River. Hoadley and Thomas produced tall case clocks together until 1814. Seth Thomas also moved to the Naugatuck River in Plymouth Hollow, a section of Plymouth that later split off in 1875 and was named Thomaston in his memory.

The Shelf Clock

Connecticut clocks in the early 19th century were primarily tall case clocks. Clocks that rested on a shelf or mantel were not yet produced, other than some made by the Willards in Massachusetts. Eli Terry designed a new prototype clock in 1813 called ‘The Box Clock.’ These clocks had a square case, and there was no dial to cover the gears, so numerals were painted directly on the glass door. The exposed gears added to the charm of this shelf clock. The popularity of these clocks set a new standard for Connecticut-made timepieces.

During this period, other people flooded to the area to begin producing clocks thanks to high demand for Terry’s clocks. Ephriam Downs, George Mitchell, Heman Clark, Riley Whiting and many others moved to Bristol, Waterbury and Plymouth to begin making clocks for themselves.

In 1815 Terry transformed the clock market again with the Pillar and Scroll Clock. This handsome clock had a 12×12-inch face, a beautiful reverse glass painting on the door and 20-inch pillars on each side with a fancy carved scroll on the top.

The Pillar and Scroll clock sold for about $15, and was distributed from door to door and town to town by Yankee peddlers on wagons.

In 1825, a former apprentice of Eli Terry named Chauncey Jerome designed a new clock called the Bronze Looking Glass Clock. This new design changed the entire industry again. Terry quickly adapted his factories to produce similar models of cases. Eli Terry produced Pillar and Scroll Clocks well into the 1830s, as well as dozens of other newer designs.

The Next Generation

Eli Terry’s two sons Eli Jr. and Henry also took up clock making, and in 1823 he established Eli Terry & Sons. At first, clocks were produced at a rate of about 6,000 a year, which increased dramatically to 10,000 and then 12,000.

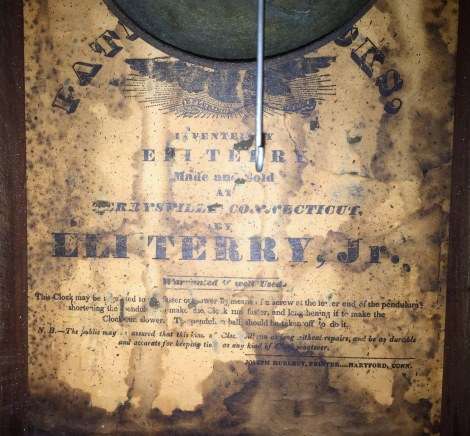

Eli Terry, Jr., left the firm in 1828 and moved to eastern Plymouth, where he built a new clock factory. He produced shelf clocks until his death from overwork in 1841. This section of town was named Terryville in his honor. The waterwheel used to power the junior Terry’s factory is still standing today across from his home. Henry Terry left the firm in 1832 to start a silk factory, which ultimately failed.

Eli Terry’s son Silas B. Terry also moved to Terryville. Silas opened up a clock factory making brass shelf clocks under the name Terry Clock Company. He used his father’s patents, which boosted the industry. He later moved his factory to Waterbury, then Massachusetts.

When Eli Terry, Jr., died, Hiram and Heman Welton purchased his clock factory and made wooden gear clocks. Due to patent issues, the Weltons were sued. Eli Terry designed a new clock patent and gave it to the Weltons.

Legacy

Eli Terry retired from clock making in 1833, but that didn’t stop him from making clocks in his free time. Terry began making fine high-quality brass wall clocks just as he did when he first began clock making. He even built three tower clocks for local churches, one of which still works today in the Plymouth Congregational Church.

Eli Terry died Feb. 24, 1852. His last clock, a simple box-shaped wall clock, hangs in the American Clock and Watch Museum in Bristol, Conn.

Terry’s masterpiece clocks are on display in museums all across the country, including the Wadsworth Atheneum, Yale University Art Gallery and the Smithsonian Museum of American History.

Tom Vaughn is the vice president of the Plymouth Historical Society and a clock collector. He also has an ongoing passion for local history. You can see the Plymouth Historical Society’s website here and Facebook page here. All photos except the Plymouth Congregational Church are courtesy of Tom Vaughn and the Plymouth Historical Society. This story was updated in 2024.

9 comments

[…] Walter Camp was born in New Britain, Conn., on April 7, 1859, into the family that owned the New Haven Clock Company. Chauncey Jerome had founded the company in 1817 and made a fortune by selling cheap clocks with brass works. A devastating fire and Jerome’s own mistakes allowed his nephew, Hiram Camp, to take over the company. By the time Walter was born, the New Haven Clock Co. was the world’s largest clockmaker. […]

[…] roving and carding cotton. It was a dream come true for Sam Slater – and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in […]

[…] built a general store with doors opening onto the canal for dropoffs, which included the original Eli Terry clock […]

[…] women hired to paint luminous paint onto the popular new watch dials in Connecticut – in Waterbury, Bristol, Thomaston and New Haven – and in Orange, N.J., and in Ottawa, Ill. She was also one of dozens who died from radium […]

[…] Samuel Bemis did learn how to make clocks and watches from his father, from whom he apparently inherited mechanical aptitude. He moved to […]

[…] bell maker in Connecticut. The state that produced the Frisbee, the lollipop, the can opener, the box clock and the Mickey Mouse watch also once made nearly every small bell in the United States and […]

[…] About the author: Thomas Vaughn is vice president of the Plymouth Historical Society and a clock collector. He also has an ongoing passion for local history. You can see the Plymouth Historical Society's website here and Facebook page here. For a story by Thomas Vaughn about Connecticut clockmaker Eli Terry, click here. […]

Hello,

I’m doing some research on an old Eli Terry and Son clock my wife has that was handed down to her from her grandfather. I intentionally said “Son,” not “Sons,” because that is what the label inside the clock says. Apparently this clock was made before Henry was a partner in the company, and only Eli Junior was partner. I came across an article from 1970 by the National Association of Watch and Clock Makers stating that Henry Terry had written an “open letter” in 1853 that was published in the Waterbury American. The NAWCM explained in the 1970 article that “Henry had been taken into the firm of Eli Terry & Son (no “S”)about 1818, when the firm name was changed to Eli Terry & Sons.”

Your article states that Eli Terry and Sons was established in 1823, so I’m a little confused about the dates. It’s apparent that I may have a more rare clock than I originally had thought, and would be compelled to think it was manufactured somewhere between 1814 and 1818, but I’m not so sure. Thoughts?

We suggest you contact Tom Vaughn, the story’s author. You can reach him at [email protected]. Good luck!

Comments are closed.