Elizabeth Stuart Phelps more than 150 years ago wrote about how hard it was for women to balance their ambitions with home and family.

Now largely forgotten, her work appeared in books and publications next to Mark Twain, Henry James and William Dean Howells.

She wrote 57 books, all of which challenged the view that a woman’s place was in the home. She was the first woman to deliver a series of lectures at Boston University. A reformer, she questioned religious dogma, opposed animal experimentation and tried to change women’s clothing. She urged them to burn their corsets.

Burn up the corsets! … No, nor do you save the whalebones, you will never need whalebones again. Make a bonfire of the cruel steels that have lorded it over your thorax and abdomens for so many years and heave a sigh of relief, for your emancipation I assure you, from this moment has begun.

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps was born Mary Gray Phelps Aug. 31, 1844 in Andover, Mass., the daughter of a prominent Congregational minister, Austin Phelps. He was president of the Andover Theological Seminary, an orthodox Protestant institution that required students to build coffins as a reminder that life is brief.

Her mother, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, wrote the Kitty Brown series of children’s books. (You can still buy them on Amazon.) She died of brain fever when Mary Gray was eight, and Mary Gray asked to change her name in her mother’s honor.

Elizabeth’s first story was published in Youth’s Companion when she was 13. At 19 she had a Civil War story published by Harper’s Magazine.

Housework and Heaven

Her father remarried twice and had more children, which left Elizabeth with much of the responsibility for the housework. She wasn’t happy about it. “Must I cut out underclothes forever? Is this LIFE?,” she wrote.

She couldn’t attend Philips Andover, despite her father’s position there (he held a feudal attitude toward women, anyway). But she did manage to get a good education at Mrs. Edwards’ School for Young Ladies.

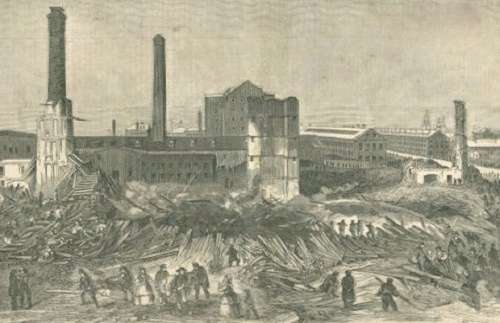

In 1868, at 24, she published The Tenth of January about the tragic Pemberton Mill collapse, which killed 145 workers and injured 166. The story won the admiration of John Greenleaf Whittier and Thomas Wentworth Higginson.

The Pemberton Mill, collapsed.

That same year she published The Gates Ajar to comfort, she said, a generation of women who lost loved ones in the Civil War. She described heaven as a place where families, including their pets, would be reunited. It was widely successful, selling more than 100,000 copies. Her depiction of heaven as something other than a place to meet God provoked controversy, which only spurred more sales.

The book inspired spin-off products like cigars, funeral wreaths and patent medicines, even a parody by Mark Twain, Captain Stormfield’s Visit to Heaven.

A Gates Ajar floral arrangement

The story of Avis in 1877 portrayed a woman’s struggle to balance marriage and family with her desire to be a painter. It may have presaged h own marriage.

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward

Herbert Dickinson Ward

In 1888, at 42, she married Herbert Dickinson Ward, a journalist 17 years her junior.

The marriage didn’t succeed. They spent most of their time apart. She was busy writing a total of 57 books of poetry, fiction and essays. In all, she argued women did not belong primarily in the home as financial dependents of their husbands.

In a letter, she wrote, “Marriage s such tremendous material for the novel-writer! I wonder that it is not worn out in the using. But the married are hampered in what they can say.”

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward was not at all hampered. In 1902 she wrote a novel, Confession of a Wife. The plot involves a determined suitor who overcomes her reluctance to marry him. But he soon tires of her, gets addicted to morphine and moves to South America. In the novel, they reconcile. In real life, they didn’t.

She was the first woman ever to deliver a lecture at Boston University. Elizabeth also contributed to a novel, The Whole Family, in which 12 prominent authors each wrote a chapter in the voice of a family member. (It was a mess.)

Later in life she got involved in the anti0vivisection movement.

Always sickly, she died at 66 on Jan. 28, 1911, in Newton Centre, Mass. Her husband wasn’t there.

This story last updated in 2023. With thanks to Elizabeth Stuart Phelps: Selected Tales, Essays and Poems, edited by Elizabeth Duquette and Cheryl Tevlin.

2 comments

Love these stories!

[…] or scantily clad, the Gibson Girl represented his ideal woman. She was depicted as a student, as a writer, as a working woman and as an athlete. Above all, she was depicted as the superior of the sexes. […]

Comments are closed.