During the bitterly cold January of 1912, the mostly young immigrant women who worked in the textile mills of Lawrence, Mass., walked off the job demanding bread and roses. They wanted enough money for bread, and thy wanted dignity and respect.

Lawrence mills by 1912 produced more worsted goods than anywhere else in the United States. The population nearly doubled from 1890 to 1910. Italians, Poles, Lithuanians and Armenians and other new arrivals packed into tenement slums.

The workers suffered abysmal conditions in the mills. Most of the workers earned $9 a week. A Lawrence doctor reported “36 out of every 100 of all men and women who work in the mill die before or by the time they are 25 years of age.” Half of all children died before they were six. The workers and their families suffered from malnutrition, occupational illnesses, accidents and the grueling work.

Bread and Roses Strike Begins

Camille Teoli, a young Italian immigrant, worked in the Washington Woolen Mill. Soon after she started work, the machine speeded up and caught her long hair, scalping her. She spent seven months in a hospital. Two years later she went back to work, though a doctor was still treating her for her injury, because her family needed the money.

To ease the harsh working conditions, the Massachusetts Legislature cut the work week to 54 from 56 hours, effective Jan. 1, 1912. On January 11, Polish weavers at the Everett Mill got their first paychecks since the law took effect. Their pay had been cut by 32 cents, enough to buy three loaves of bread – a staple of their diet of bread, molasses and beans. The Polish women shut down their looms and walked out.

The strike spread quickly throughout the huge mill city. As many as 25,000 walked off the job to the cry, ‘Short pay, all out!’ Most were women between the age of 14 and 18, and nearly half had been in the country for less than five years.

Wobblies

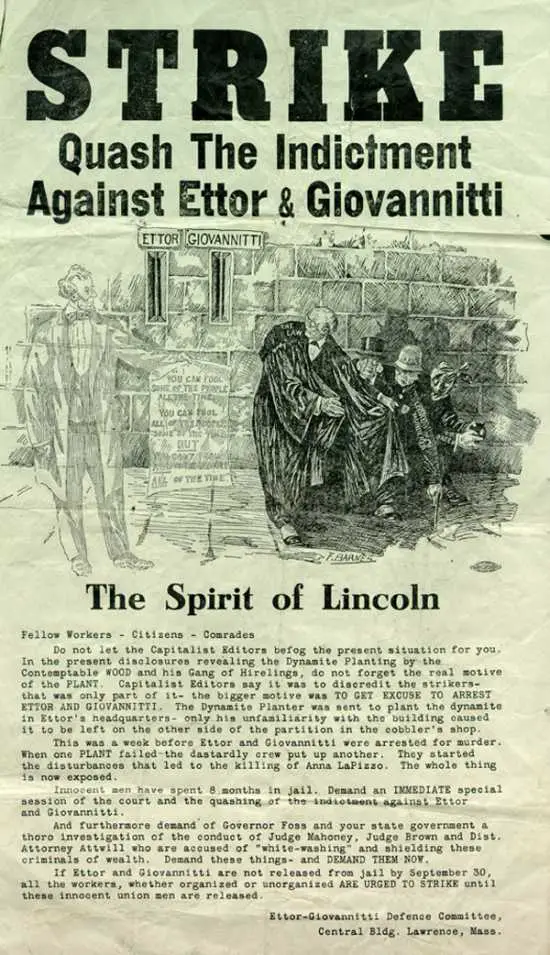

The Industrial Workers of the World, known as the Wobblies, had tried to organize the workers for five years, with little success. IWW organizer Joseph Ettor and Arturo Giovannitti of the Italian Socialist Federation assumed leadership of the strike. IWW organizers Big Bill Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn later joined them.

They set up a strike committee with two representatives from each ethnic group. Strike communications had to be translated into as many as 25 languages, and in 25 languages they demanded a 15 percent pay hike, double time pay for overtime and no retaliation against strikers.

Mill owners turned fire hoses on the picketing strikers, who threw ice or rocks and broke the mill windows. One cold morning after the hoses drenched the women the strikers caught a policeman in the middle of a bridge and stripped off his uniform. Other policemen had to save him from getting thrown in the river. Three dozen strikers were arrested and sentenced to a year in jail for damaging property. A local undertaker planted dynamite around town in an attempt to frame the strike leaders. He received a fined, but no jail time.

Gov. Eugene Foss called out the state militia to quell the Bread and Roses strike. Police arrested many of the strikers. A bayonet stabbed one striker, a stray bullet killed another. Authorities tried to frame Ettor and Giovanetti for the striker. They were exonerated in November during a trial in which they were held in metal cages in the courtroom.

Safety

In late January, the strikers sent 100 children to New York City to keep them out of danger. They arrived to cheering crowds of thousands of supporters.

On February 24, the strikers tried to send another 100 children to Philadelphia, but the Lawrence City Marshal tried to stop them. Marshals and police clubbed mothers and children before dragging them away to jail. One woman miscarried. News photographers recorded the brutality.

That turned the tide of public opinion against the mill owners. Congress investigated, questioning workers like Camella Teoli. The mill owners caved. On March 12, 1912, the Bread and Roses strike ended.

Reader Joe DeFilippo submitted this video of a song he wrote to commemorate the strike:

This story was updated in 2022.

15 comments

[…] the spring of 1912, Connecticut newspapers were filled with accounts of the successful Bread and Roses textile workers strike in Lawrence, Mass. Thousands of textile workers, mostly immigrant women and children, had gone out on a two-month […]

[…] and assimilating them. In 1912, the issues of immigrant assimilation got a boost from the Bread and Roses Strike in Lawrence, […]

[…] Gurley Flynn went on to organize the 1912 Bread and Roses strike in Lawrence, Mass., founded the American Civil Liberties Union, chaired the Communist Party USA […]

[…] for better pay and working conditions. Arturo Giovanitti, Joe Ettor and Carlo Tresca organized the 1912 Lawrence Textile Strike, known as the Bread and Roses […]

[…] treatment by the Providence establishment. Encouraged by the I.W.W. (which sponsored the famous Bread and Roses Strike in Massachusetts), Italians had marched through the streets of Little Italy supporting labor politicians and Italian […]

[…] the aftermath of the strikes, the town of Ipswich was mindful of the Bread and Roses Strike that had taken place in Lawrence just 18 months earlier. It had lasted for months and resulted in […]

[…] Christmas 1935 approached, her family back in Lawrence hoped that 29-year-old Thelma might visit for the holidays. But on Dec. 16, 1935 Thelma was found […]

[…] Wrentham that Helen Keller became a feminist, a pacifist and a Wobbly — that is, a member of the Industrial Workers of the World labor […]

[…] out of Wisconsin a steady-eyed Republican, but the more he was exposed to inequality and the way powerful institutions banded together to oppose labor and oppress minorities, the more radical he […]

[…] Hampshire. The Whistle at Eaton Falls (1951) was set in a New Hampshire mill town and highlighted labor-management strife. It marked the film debut of Ernest Borgnine. Lost Boundaries (1949) told the story of a New […]

Hello! Does the New England Historical Society own the image used at the top of the page? My company is interested in publishing the image and are looking to get in touch with the copyright holder or owners of the original photo.

Let me know if you have any information about the image!

[…] a tramp steamer for several years. He joined the Maritime Transport Workers Union of the IWW, or Wobblies, and wrote […]

[…] the United States intervened in World War I, including the 1914 Ludlow massacre in Colorado and the 1912 Bread and Roses strike in Lawrence, […]

[…] Industrial Workers of the World, also known as the Wobblies. The Wobblies had led the successful Bread and Roses strike in Lawrence, Mass., 12 years earlier, and now they were taking on the lumber […]

[…] Company; History News Network; Bread and Roses Festival; New England Historical Society; Digital Public Library of […]

Comments are closed.