George Washington called Boston’s annual Pope Night celebration “ridiculous and childish.” But the working-class celebrants, especially the young men, loved the wild partying in the streets. It was the biggest holiday of the year (after all, the Puritans had banned Christmas).

Celebrated on November 5, Pope Night was an American version of England’s Guy Fawkes Day, and it was decidedly anti-Catholic. Fawkes, a Catholic partisan, had tried to blow up Parliament.

Plymouth, Mass., celebrated the first recorded Pope Night in 1623 when sailors lit a bonfire. The fire blazed out of control and burned down several nearby homes. That was so much fun the other seacoast towns took up the celebration. Pope Night spread to Marblehead, Newburyport and Salem in Massachusetts, Portsmouth in New Hampshire and New London in Connecticut. The festivities generally featured fires, drinking and mockery of elites and authorities.

Boston’s Pope Night

In Boston, the night started with two parades, one in the North End and one in the South End. Both featured an outsized effigy of the Pope, the devil or a hated political figure. Costumed revelers pulled the figure through the streets in a decorated cart, much like Mardi Gras.

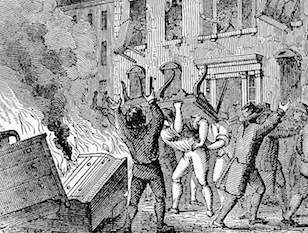

Detail from a 1788 broadside showing Pope Night in Boston

The parades ended with the two sides meeting and brawling. The winning side would take the cart, the money and the effigies of the loser, then burn the effigies in a bonfire and spend the money on a feast. The North Enders would do it on Boston Common, the South Enders on Copps Hill. People were killed or maimed in the fighting, and the town only had a handful of constables who couldn’t control the mob.

In America, as in England, the holiday had political overtones: Americans had been fighting the Catholic French for decades. Anti-Catholic sentiment got a boost in 1774 when the British Parliament passed the Quebec Act. It guaranteed the free practice of the Catholic religion in Canada and granted the Ohio territory to Canada.

1777 map by William McFadden showing how Quebec encroached on the American colonies.

But Pope Night had further historical importance. The civic groups that staged the parades and the partying provided the structure and the leadership for resistance to the Stamp Act. In 1765, the Loyal Nine (predecessors to the Sons of Liberty) arranged the union of the North and South end mobs. The joined gang rioted against the Stamp Act, forcing stamp collector Andrew Oliver to resign and ransacking the mansion of Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson.

Attack on Hutchinson’s house

Kissing the Devil

In 1821, a 70-year-old man recalled for the Boston Advertiser the carriages hauling the Pope. He called it “a large stage erected on wheels,” upon which a gorgeously attired Pope sat before a table scattered with playing cards. Nancy Dawson, a “female figure in an attitude of dancing,” stood behind him. The float also included an effigy of Admiral Byng, a British naval officer shot for refusing to fight, and a hideous devil covered with tar and feathers. Boys wearing dresses and trousers covered with tar and feathers danced around the Pope and kissed the devil.

In 1749, the Boston Gazette printed a notice about the “Pope’s Night Disaster.”

Last Monday, the 6th Instant, at Night, some of the Pope’s Attendance had some Supper as well as Money given ’em at a House in Town, one of the Company happen’d to swallow a Silver Spoon with his Victuals, marked IHS. Whoever it was is desired to return it when it comes to Hand, or if offer’d to any Body for Sale, ’tis desired it may be stop’d, and Notice given to the Printer.

In late 1775, Continental Army Commander-in-Chief George Washington wanted to win the support of French-Canadian Catholics as his army prepared to invade Canada. He also wanted to keep the colonies — including Catholic Maryland — united. Meanwhile, Silas Deane and Benjamin Franklin were in France, persuading the French to support the American cause.

George Washington by John Trumbull

Then headquartered in Cambridge, Mass., Washington put a stop to Pope Night. He called it ‘that ridiculous and childish custom of burning the Effigy of the pope.’ He called it improper ‘ at a time when we are soliciting, and have really obtained the friendship and alliance of the people of Canada.’

…[I]nstead of offering the most remote insult, it is our duty to address public thanks to these our brethren, as to them we are indebted for every happy success over the common enemy in Canada.

Death of Pope Night

Pope Night returned in 1776 and 1777, but then the French arrived to aid the Americans in the war. Pope Night came to an end. Even the revelers realized it would have been unseemly to mock the religion of the king who sent the money, men and arms that won the American Revolution.

The British surrendering to French and American forces at Yorktown. Painting by John Trumbull.

Pope Night died a richly deserved death — sort of. Two features lingered: bonfires and dressed-up boys going door-to-door. As the writer in 1821 recalled,

…boys in petticoats…swarmed in the streets and ran from house to house with little Popes in their hands, on pieces of board and shingle, the heads of which were carved out of small potatoes.

The boys asked for coins as they rang handbells and sang a song. It went,

Don’t you hear my little bell

Go chink, chink, chink?

Please to give me a little money

To buy my Pope some drink.

The tradition evolved into ‘Pork Night.’ Eventually it moved up a few days and became what we now know as Halloween.

If you enjoyed this story about Pope Night, you may also want to read about Christmas in New England here.

With thanks to Nutfield Genealogy and Boston 1775 This story was updated in 2023.

Map image: By William, 1750?-1836 — Engraver Faden – digitalgallery.nypl.org, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=55159836.

8 comments

[…] the blood flowed freely. However, I wiped my face, and getting out the Bishop's robe, put it on in a spirit of deviltry. The others stripped it off my back, and winding the remnants around poles, used them as torches, […]

On one of those early “Pope Nights,” the South End gang’s wagon threw a wheel. A burly young Scots-Irish boy substituted his brawn for the missing wheel and both gangs cheered. This kid would eventually escape the life of a street ruffian and be taken under the tutelage of a book store owner. The kid got into books, especially on the military sciences, including artillery, and eventually opened his own bookstore. As a young man in the winter of 1775-76 he dragged the guns of Fort Ticonderoga on skids across the Berkshires to be place upon Dorchester Heights. He would become Washington’s chief artillerist and one of his closest confidants, and America’s first Secretary of war – Henry Knox. He was not the first American to pull himself up from just about nothing, and he certainly was not the last.

I enjoyed the article about Pope’s Night developing into Halloween, and all the polítical background. Excellent!

[…] weren’t pies floating around New England at the time,” said Cox. Those false pies were called Washington Pies, light cakes with a cream or fruit filling. Lafayette Pies were […]

[…] Puritans. They rejected the Anglican and Catholic view of marriage as a sacrament, thinking it a 'popish invention, with no basis in the Gospels.' They redefined marriage as a civil matter only. If a […]

[…] knew well of American attitudes toward Catholics. He had tried to quell anti-Catholic sentiment by banning Pope Night in Boston in […]

[…] were led by separatists who despised the Christmas traditions of the Anglican Church as well as the Roman Catholic Church. They wanted to establish their own protestant churches, free of Christmas. But many of the […]

[…] pies floating around New England at the time,” said Cox. People called those false pies Washington Pies, light cakes with a cream or fruit filling. Lafayette Pies resembled the Washington […]

Comments are closed.