On the morning of Dec. 6, 1917, a curious telegraph arrived at the offices of Hornblower & Weeks, a Boston investment banking firm. George Graham, the company’s man in Halifax, sent it to J.J. Phelan, a partner in the firm. The telegraph outlined the sparest details of a disaster later known as the great Halifax explosion.

Governor McCall in 1918 amid the reconstruction following the Halifax explosion. Note the signs on the building.

The message read simply: “Organize a relief train and send word to Wolfville and Windsor (towns near Halifax) to round up all doctors, nurses, and Red Cross supplies possible to obtain. Not time to explain details but list of casualties is enormous.”

One of the casualties of the Halifax explosion was communication. The explosion had destroyed most telegraph lines to Halifax, and the Canadian government took over the few remaining.

So on the strength of that one cryptic telegram from George Graham, Massachusetts quickly assembled a massive relief team and sent it to Halifax.

Phelan and McCall

J.J. Phelan was a man of action. He had risen in the firm of Hornblower & Weeks from the position of clerk to partner on the strength of his hard work.

Earlier in the year, as the U.S. prepared to enter World War I, Phelan agreed to serve on the governor’s Committee on Public Safety. The committee had one overriding goal: to make sure the war did as little damage to Massachusetts as possible.

Phelan was attending a meeting at the Massachusetts Statehouse that December morning as part of his committee work. An aide approached and hurriedly called him to the telephone. The contents of the telegram from Halifax were read to him.

Phelan immediately left the room for the governor’s office down the hallway. Phelan, a Republican, and Samuel McCall, the state’s Democratic governor, were not natural political allies. But the curious telegraph message demanded action.

Halifax’s Exhibition Building. The last body was recovered from the explosion in this building — in 1919.

Governor McCall tried to find more information. Well-connected after 20 years in Washington as a congressman and newspaper editor, McCall, surprisingly, could get little clarification. All anyone seemed to know was that some kind of fire or explosion had happened in Halifax. McCall fired off a message of his own to the mayor of that city. “Understand that your city in danger from explosion and conflagration,” it said. “Reports only fragmentary. Massachusetts ready to go the limit in rendering every assistance you may be in need of. Wire me back immediately.”

With that, McCall turned to his Committee on Public Safety – the 100 men from industry that McCall had assembled earlier that year.

Rapid Response

The committee reached out to the banks, the railroads and the universities represented on its board. Harvard University emptied its medical school and, with the Red Cross, packed up the makings of portable surgical suites. Nurses from the hospitals volunteered to go. The banks assembled cash.

The head of the Boston and Maine Railroad promised a train if the governor would fill it. By 10 o’clock at night, less than 12 hours after the initial telegraph, the train left for Halifax. All of those who responded still had no information beyond the initial cry for assistance and warning of enormous casualties.

When the train arrived in Halifax, after a blizzard delayed it, its passengers realized the enormity of the disaster.

U-Boat Nets

Halifax served as a key British port during World War I. Ships heading across the Atlantic made routine stops in the port. Well-sheltered, it made a difficult target for the German U-Boats that terrorized commercial shipping in the Atlantic.

In addition to the natural protections, the city had erected a steel chain net. It raised the net each night and lowered it each morning to prevent any German submarines from slipping in to damage the ships.

On the evening of December 5, a Norwegian vessel, the SS Imo, faced a delay in leaving port while it searched for a harbor pilot to guide it out. Meanwhile, a French ship, the SS Mont–Blanc, had stopped outside the mouth of the harbor while it waited for a pilot to guide it safely inside.

Both ships had frozen in their positions when the city raised its anti-submarine net. On the morning of December 6, they were eager to get on their way – the Mont-Blanc entering the harbor and the Imo exiting.

The Imo was empty, stopping in Halifax on the way to New York to obtain relief supplies for war-torn Belgium. Unknown to anyone but its crew, explosives filled the Mont-Blanc hold. They had suspended the use of red flags that traditionally warned of explosive cargo because they made a ship an easy target for the Germans.

As the Mont-Blanc made its way into the harbor, the pilot grew concerned that the Imo obstructed its path. A passing, incoming ship had forced the Imo into the wrong side of the channel. The Mont-Blanc sounded a warning blast of the ship’s whistle. The captain of the Imo sounded a blast, indicating that he intended to stay on his course.

The Mont-Blanc immediately stopped its engines and sounded another warning, but the Imo pressed forward. On shore, it became clear that a collision was near, and sailors and dock hands gathered to watch.

The Halifax Explosion

With the Imo’s engines now stopped, the two ships drifted toward one another. The pilot of the Mont-Blanc did not dare to ground the ship for fear of explosion, but efforts to steer clear of the Imo failed. The Imo struck the side of the Mont-Blanc, toppling some barrels of benzene on the French ship’s deck, spilling the volatile liquid into the holds of the vessel.

Red Cross workers ready to treat victims of the Halifax explosion in temporary quarters in the YMCA.

The Imo then put its engines in reverse, and as it backed away, sparks generated by the two hulls grinding together ignited the benzene. Only the men of the Mont-Blanc understood that a fuse had been lit. The Mont-Blanc’s captain ordered the men off the vessel and they gave up efforts to stop the fire. Instead, they headed for the nearby Dartmouth shore.

After they landed, the sailors tried to warn people on the shore, but the French-speaking sailors could not make themselves understood. Moments later, the munitions in the Mont-Blanc exploded – the most powerful explosion ever produced up until the advent of nuclear weapons. The effects on Halifax and Dartmouth were catastrophic.

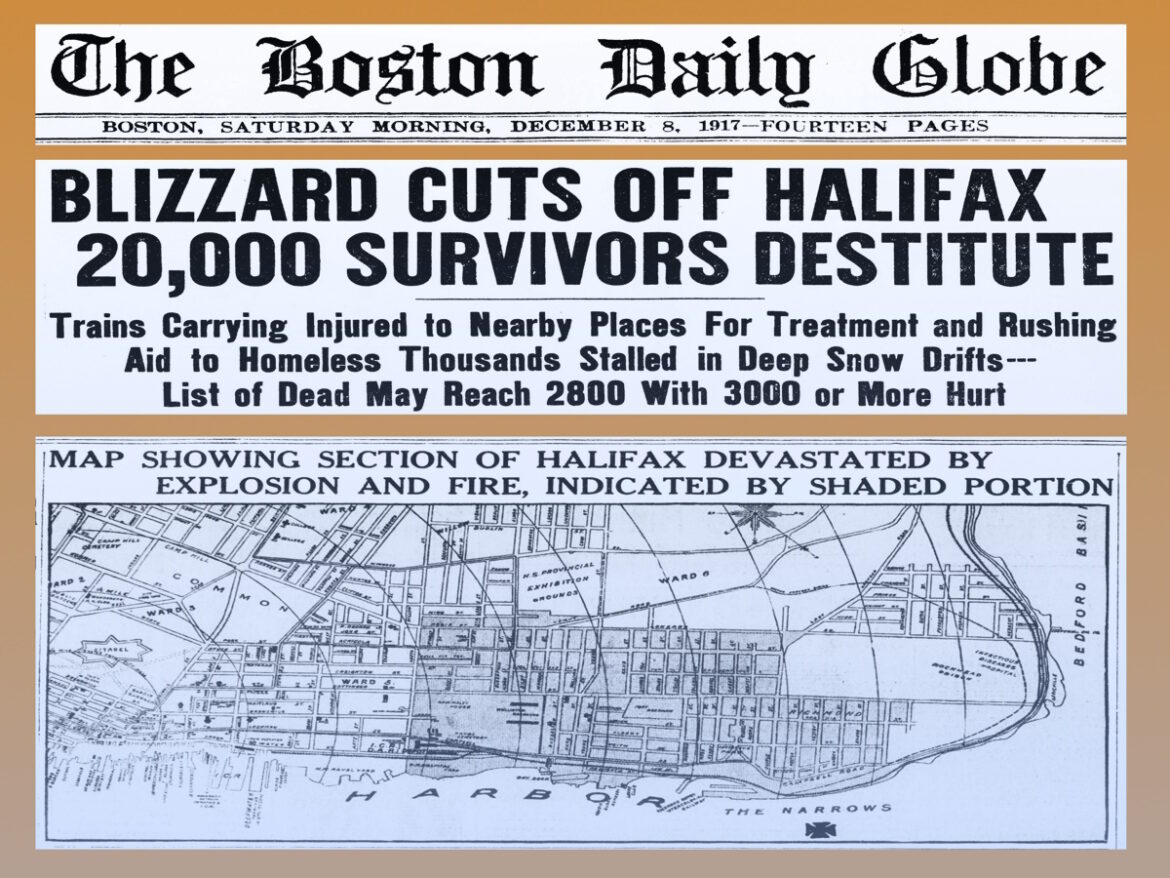

The Halifax explosion blew down entire city blocks, killed an estimated 2,000 people and injured 9,000. The blast disabled communications and firefighting apparatus. It was only through a stroke of luck that Hornblower & Weeks’ private telegraph line could send a message to Boston.

Train Arrives

As soon as the Massachusetts physicians, nurses and supplies arrived by train, they went to work. Back in Boston, meanwhile, the Committee on Public Safety began assembling a warehouse full of relief supplies. They collected furniture, kitchen goods, food, bedding, lumber – everything needed to rebuild after the Halifax explosion.

The relief committee loaded the materials onto a ship that left for Halifax. In the weeks ahead a store was set up for displaced families to visit and take what they needed to rebuild their lives. As word of the Halifax explosion spread, cities and towns across America and Canada helped repair the shattered city.

Temporary housing was built to replace what had been demolished. In recognition of Massachusetts’ rapid response, Halifax christened the temporary Governor McCall Apartments on the newly-created Massachusetts Avenue.

For each year since, the people of Halifax have given to the city of Boston a tall spruce tree as a Christmas gift. The tree recalls the day the Canadian city asked for aid from its American cousins and, despite limited knowledge of what had happened, a U.S. city and a commonwealth responded to the Halifax explosion.

* * *

A great gift for anyone who grew up Italian in New England. Available in paperback or as an ebook from Amazon. Click here to order your copy.

This story about the Halifax explosion was updated in 2023.

Images: Halifax Explosion Christmas tree by By Louis Oliveira from Warwick, RI – Xmas tree on Boston Common, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37635230

13 comments

Thanks for sharing this story. I learned something new. Very interesting.

An incredible story of a wartime tragedy. 2,000 people dead and 9,000 injured. It happened less than 100 years ago, but I would bet that most people today know nothing about it. It gives you some perspective on how modern events will be remembered. (Or not)

I, too, have visited Halifax and heard the stories. Remember when the 2 747s collided on Tenerife in 1977? Similar case of an avoidable accident where human stubbornness was a contributing factor.

My husband and I drove all over Cape Breton and Nova Scotia in the fall of 2009. A motel owner gave us his copy of Shattered City to read while we were there. The last survivor of this terrible accident had just passed away. He was a little boy playing with a toy on a windowsill at the time of the explosion and was blinded by flying glass as I remember. My maternal grandmother was a “herring choker” so stories of Nova Scotia were always of interest to me.

As a young boy my family would vacation in NS to visit my Aunts and Uncles (maternal). One Uncle would tell us kids the story about that blast, as he worked the docks and had been hit by shrapnel and knocked him out. We all had to feel the depression on the side of his head, where he was hit that dreadful day.

In “Burden of Desire,” Robert MacNeil, of the MacNeil/Lehrer Newshour, writes about incident and the record number of eye injuries due to so many watching the burning ships in the harbor from the windows of their homes which smashed at the time of the explosion.

went there a few years ago to see where my dads family lived = you have to see it in person to grasp how big an area it covered = the pictures in the museums make the damage from recent tornados in the states look like childs play = an explosion of that magnitude with the density of Halifax today the casualties in the high thousands and the damage in the hundred of millions

I grew up in the part of Halifax most heavily affected by the Explosion but fifty years later fortunately. We did however have the beautiful oak dining room set – referred to reverently as the Massachusetts Tree Trunk table set – in my childhood home. I had the benefit of a number of relatives who lived through the Explosion and you’ll be happy to know that they all spoke of Boston’s efforts with gratitude and warmth. I believe your state archives has a trove of photos taken by your relief team. As we are approaching the 99th anniversary on Dec 6 and of course the 100th next year, I’m sure many would appreciate if they could be posted on line. You may be interested in the NS Archives collection of pictures here https://novascotia.ca/archives/virtual/?Search=THexp&List=all

My relatives are some of the kids in the photo above. My great uncle Charlie is the baby in the Stroller. He would later become Mayor. These efforts of assistance saved many lives and to this day as a 50 plus year old I find my eyes watering yet again thinking of my great grandparents, my grandfather, his siblings and all others here. I owe you such a debt, that I can never repay it. My grandfather said this, my father said this, I say this, and my children will say this. Thank you and Merry Christmas.

Love

Ted Vaughan

Halifax

My grandfather was the pastor of St Matthews Church on Barrington Street very near to the explosion, in Halifax at the time and my Dad, Ewan and his brother Bill, were in school at Morris Street school that morning. Their teachers led them down the stairs to the basement of the school but what they saw, breaking glass, injured children and the drama of it all stayed with my Dad for the rest of his life. He wrote a charming message to his granddaughter many years later describing what they went through and of the help they and parishioners were able to provide for those affected. We heard stories that family in Truro, many miles away, heard and felt the blast.

[…] and the Canadian Broadcast Corporation have recently done stories on the 100th Anniversary. The New England Historical Society also has a web page discussing the Explosion and Boston’s […]

In the sixth paragraph, a reference to WWII should reference WWI, if I am not mistaken.

You are correct! Thanks for pointing out the error. It’s been corrected.

Comments are closed.