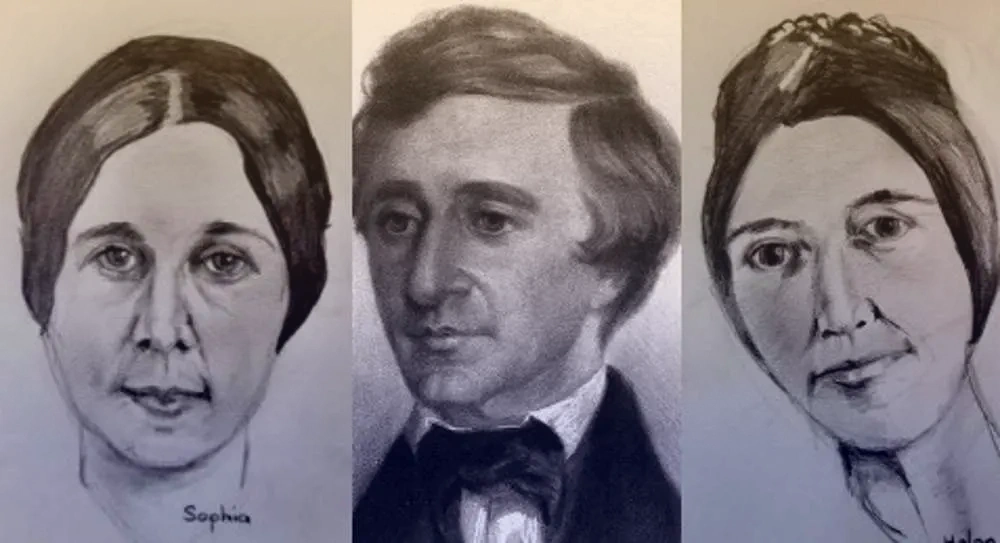

Henry Thoreau wouldn’t have been Henry Thoreau without his sisters, Helen and Sophia Thoreau. Or his brother, for that matter. But John Thoreau got plenty of ink in the book A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. Helen and Sophia, not so much.

Helen and Sophia played huge roles in shaping the writer, naturalist and author who influenced Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Nelson Mandela. Helen believed in him when others thought him a kook. He and Sophia grew so close toward the end of his life that a friend called them ‘like twins.’

Sophia Thoreau’s favorite image of her brother Henry

None of the Thoreau children married, and most of them, for most of their lives, belonged to the family household in Concord, Mass., along with aunt, uncles and servants. By all accounts, they had a happy home, marred only by early death.

During Henry’s two years, two months and two days at Walden Pond, Helen and Sophia came to visit him. And he often came home to visit them.

“Without such a stable and contented home life, Thoreau could not possibly have pursued his career in the way that he did,” wrote his biographer Laura Dassow Walls.

The Yellow House

The entire Thoreau family loved nature, and Sophia Thoreau in particular shared Henry’s passion for botany. As children they hiked together around Concord, collecting rocks, lichens and plants. Henry liked to collect arrowheads.

Henry left Walden in the fall of 1847 to babysit Ralph Waldo Emerson’s children while Emerson lectured in Europe. When Emerson returned in the summer, Thoreau went back to live with his family and help with the family business – making pencils.

The Yellow House today. Image courtesy Google Maps.

In 1850, the family had a stroke of good fortune with the development of a new and lucrative use for the plumbago used to make pencils: electrotyping. The Thoreaus began selling their ground plumbago to commercial customers. That allowed them to move to the Yellow House in one of Concord’s best neighborhoods. Henry had the attic, which stretched the length of the house, and there he kept his bed, his writing desk, driftwood book shelves, manuscripts and specimens. (The house, by the way, went on the market in 2019 for $2.6 million.)

A family friend called the Thoreau house a “haven,” a place of “undisturbed orderliness,” with a sunny sitting room filled with Sophia’s plants.

“I recall the reading aloud of fresh new books, the evening games of chess and backgammon; the bright, often distinguished people who came to the house; the tea-parties and evening visits; the lyceum lectures on cold winter nights, the walks by field and river.”

Underground Railroad

The house served as a haven of another kind: a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Helen and Sophia Thoreau, like nearly all the women in Thoreau’s life, held strong anti-slavery views considered radical at the time. His mother, aunts and sisters belonged to the Concord Ladies’ Antislavery Society, one of the first in the country.

The family proudly displayed on its mantelpiece a Staffordshire figurine of Uncle Tom and Eva, the main characters in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Legend has it that a fugitive from slavery gave it to them as a thank you for their help.

Staffordshire figurine of Eva and Uncle Tom.

When fugitives arrived at the Thoreau household, Henry often took them to the railroad station, bought them tickets and gave them money. Sometimes he got on the train with them, either in Concord or in Fitchburg.

During his stay at Walden, Thoreau sheltered runaway slaves during the day in his cabin and escorted them to his family home at night.

Though the Underground Railroad conductors and safe houses operated in the strictest secrecy, Henry Thoreau occasionally slipped. On Oct. 1, 1851, he wrote, “Just put a fugitive slave who has taken the name of Henry Williams into the cars for Canada.” Williams may have given them the Staffordshire.

Helen Thoreau

People suspected that Helen, of all the Thoreaus, “had more sympathy in his [Henry’s] peculiar way than perhaps any other.”

Helen Thoreau

As Henry neared graduation from Harvard, he asked his mother what he should do after college. His mother, who had a biting wit, said, “You may buckle on your knapsack, dear, and seek your fortune in the world.”

Helen, the eldest, knew the remark stung. She put her arms around him and said, “No, Henry, you shall not go; you shall stay at home and live with us.”

All four Thoreau children – including Henry – worked as schoolteachers during their lives. Helen, born in 1812, did it first. Walls described her as ‘a bookish young woman – elegant, graceful, earnest, and quiet, the family’s moral lodestar… she took the outrages of social injustice most deeply to heart, dedicating herself to ending slavery in America.’

She befriended Frederick Douglass and exchanged letters with him. William Lloyd Garrison published her obituary in his abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator.

Helen had as independent a mind as her little brother. In 1842, the local First Parish and Trinitarian churches banned women from speaking against slavery. Helen, furious that the churches opened their doors to slaveholders but not to people who defended slaves, stopped going to services.

According to one story, it was Helen who brought Henry to the attention of their famous Concord neighbor, Ralph Waldo Emerson. Helen showed Henry’s journal to Emerson’s sister-in-law, who then showed it to Emerson.

Helen died of the Thoreau family illness, tuberculosis, in 1849 at the age of 37.

Sophia Thoreau

For the last 13 years of his life, Sophia Thoreau was Henry’s only remaining sibling and probably his closest friend and confidante. When he saw something interesting or unusual, he told Sophia.

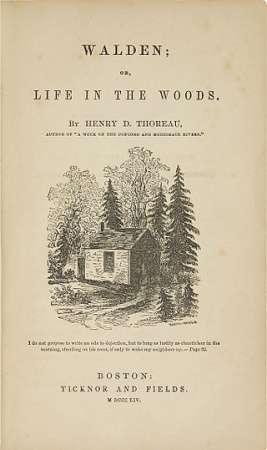

They were very much alike: musical, witty and intensely interested in botany. A family friend observed they both had “a certain gravity of thought and utterance.” Sophia also had an artistic temperament and created the famous frontispiece of Walden.

Henry was picky about who he spent time with. “I know of but one or two persons with whom I can afford to walk,” he said. “The wood-path and the boat are my studio, where I maintain a sacred solitude and cannot admit promiscuous company.” Sophia made the cut.

For her part, Sophia adored her older brother. “Henry’s whole life impresses me as a grand miracle,” she said after his death. “I always thought him the most upright man I ever knew and now it is a pleasure to praise him.”

The first night he spent away from home in his Walden cabin, Sophia worried so much she couldn’t sleep. The next day she brought him lunch, which he didn’t appreciate.

When they lived in the Yellow House, Sophia would play old Scottish melodies on the piano. Henry would come down from his attic and sing, and sometimes pick up his flute and play.

Protector of Henry’s Legacy

When Henry took to his bed with the tuberculosis that killed him at 44, Sophia not only cared for him but helped him edit his manuscripts. She also negotiated with publishers and made sure the Atlantic magazine printed several essays after his death.

She had to deal with about 60 volumes of his manuscripts and several thousand pages of notes. Thoreau’s early biographers didn’t believe Sophia was up to the task, and credited Emerson and Ellery Channing with helping her. Kathy Fedorko set the record straight.

Sophia Thoreau

“Sophia kept those manuscripts in meticulous order, selected an editor for her brother’s journal, and, on her own, edited four posthumous volumes of henry’s essays,” she wrote.

She also ran the family business after Henry died, rare for a woman in those days. A family friend remembers she had “a fine, gentle, sweet nature.” However, said the friend, “she possessed great firmness of character and was always on the side of justice.”

Every so often, Sophia visited the abandoned cottage near Walden Pond where her brother had lived. Once, she ate her dinner there, alone but for the mice.

Sophia Thoreau died in 1876 at the age of 56, the last of the Thoreau siblings.

With thanks to Thoreau: His Home, Friends and Books by Annie Russell Marble and Little Known Sisters of Well-Known Men by Sarah Gertrude Pomeroy. Also, ”Henry’s brilliant sister”: The Pivotal Role of Sophia Thoreau in Her Brother’s Posthumous Publications by Kathy Fedorko for The New England Quarterly, Vol. 89, No. 2 (June 2016). Finally, Henry David Thoreau: A Life by Laura Dassow Walls. This story was updated in 2023.