If you wanted to know your grandparents or grandchildren back in the 17th and 18th centuries, your best bet was to live in New England. That’s because New England invented grandparents.

Before Europeans came to New England, not many people in the western world ever got to know Gramps or Meemaw. Their grandparents usually died before they were born. In England, for example, most men wed just before age 30 and died in their early fifties — before their own children married and had children.

“Few people today realize how unusual it was for western European adults to become grandparents centuries ago,” wrote historian Thomas L. Purvis.

But then colonists arrived in New England, lived long lives and prospered. They had lots of children and lots of grandchildren. And along the way they figured out how to be grandparents.

How New England Invented Grandparents

New Englanders on average led longer lives than anyone in the world during much of the 17th and 18th centuries. Cold winters discouraged disease, and stable, close-knit communities helped people live longer. So did the highest living standards in the world.

Granted, infant mortality was high in colonial New England. But if you made it out of childhood you had a better-than-average chance at living a long life. In Middlesex County, Massachusetts, for example, 20-year-olds lived to a mean age of 60.5 – old enough to have grandchildren.

Anne Bradstreet, the Puritan poet, died at age 60 in 1672 — long enough to mourn the deaths of three grandchildren. “Farewell sweet babe, the pleasure of mine eye,” she wrote in her poem, In Memory of My Dear Grandchild–Elizabeth Bradstreet, Who Deceased August, 1665, Being a Year and a Half Old.

Bradstreet wasn’t the first poet to describe a grandparent’s love for a grandchild. But she did speak for the first generation of grandparents who lived among plenty of other grandparents.

For example, in 1680 Hampton, N.H., had a population of 290 children and teenagers under the age of 19. According to family information about 200 of them, 90 percent had at least one grandparent alive. Most children under five years old had three or four grandparents still living. And nearly half of those from ages 10 to 19 had at least two grandparents still alive.

Communities became inherently more stable and prosperous after New England invented grandparents. They helped teach and take care of their grandchildren, and they often shared their wealth with them.

By 1700, just 70 years after the Puritans’ Great Migration began, colonial Americans had 38 percent more purchasing power than their British brothers and sisters. By the American Revolution, they had half again as much buying power as Britons, according to economists Peter Lindert and Jeffrey Williamson.

Bringing Up Grandsons

In 1736, 58-year-old Joshua Hempstead of New London was cutting wood with his teenaged grandson, who missed his stroke and cut across his shoe. “He let fall his ax & made no noise but said “Grandfather I have cut off two of my toes,” wrote Hempstead in his diary. “He seemed to speak as if he was jesting.”

“’I have, really Grandfather’,” he said. Hempstead took him down in his arms, set him down, pulled off his shoe and bound up the injury. Then he set him on his horse and brought him home. The doctor came to the house and stopped the bleeding. The boy would be all right.

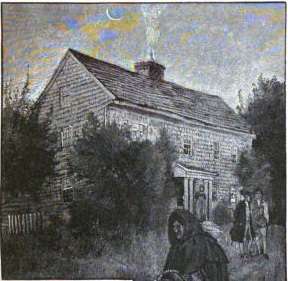

The boy’s father had died at 29, and Grandfather Hempstead, a widower, raised him and his younger brother. The older boy would inherit his house and farm, so Joshua taught him how to mow hay, chop wood, build fences and plant trees. Joshua would try to protect the two boys from injury and expose them to the wider world on his travels around the Northeast. The Hempstead homestead would stay in the family until 1937. (It’s now a house museum.)

Body and Soul

The old Puritan grandparents also used their moral authority to set high standards for their grandchildren. In 1718, a Barbados planter sent his son Richard Hall to a Boston boarding school. His Boston grandmother, Lydia Coleman, gave Richard a penny every Sunday and promised him five shillings when he could recite all the Biblical proverbs by heart.

She also conferred with his teacher, brought the teacher presents and made sure Richard had shoes and handkerchiefs.

“I would do my duty by his soul as well as his body,” she wrote.

In 1660, the Puritan minister John Wilson wanted his sickly newborn grandson to carry on his spiritual work. “Call him John,” he said. “I believe in God, he shall live, and be a Prophet too and do God Service in his Generation.” Wilson’s prediction came true, as John Danforth became pastor of the church of Dorchester.

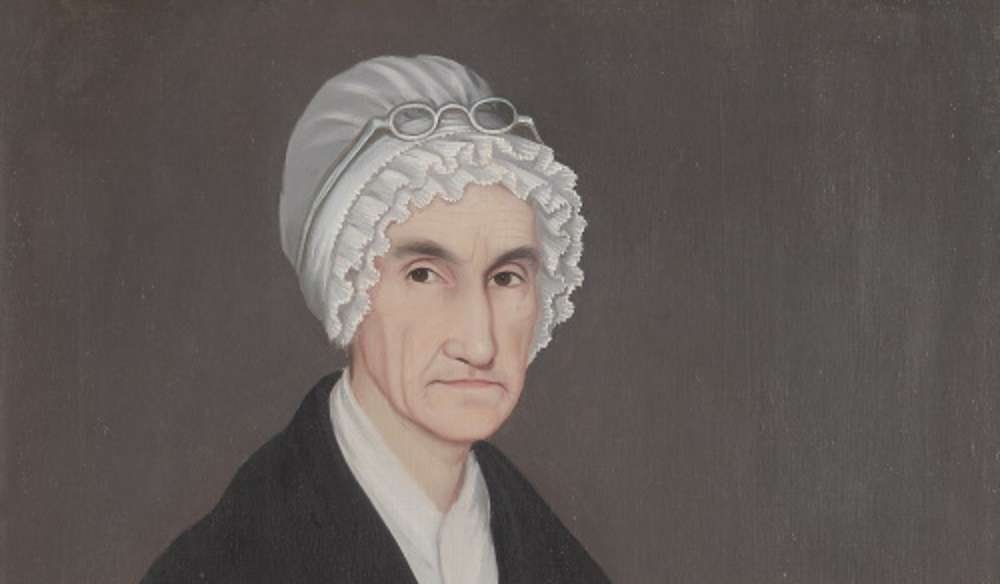

William Bentley’s parents had no interest in educating their son. So his grandfather paid for his education, and Bentley served as a minister of the East Church in Salem, Mass., from 1783 to his death in 1819.

A Sense of History

Bentley kept a copious diary. In 1812, he described how his friend Benjamin Ward had driven around Salem 52 years earlier with his grandfather. The grandfather had showed him how Salem developed: where there used to be a wharf, where the blockhouse and palisades had stood, how the channel had changed.

In such a way, New England grandparents gave their grandchildren a sense of the far-reaching importance of the early settlers.

Another diarist, Judge Samuel Sewall wrote in 1726 about meeting Thomas Faunce, an aged deacon in Plymouth, Mass., who knew many of the original Pilgrims. (Faunce is credited with saving Plymouth Rock.) Sewall described him as the ‘honored ancient elder Faunce.’

Samuel Sewall

Taking Care of Grandpa

New England grandchildren often had close ties with and affection for their grandparents. John Adams, for example, at the age of 21 visited his Quincy grandparents on Christmas Day. “The old gentleman inquisitive about the hearing before the governor and council,” he wrote. “The old lady as merry and chatty as ever, with her stories out of the newspapers.”

John Adams

His son, John Quincy, often walked over to his grandparents’ home in Weymouth, where his grandfather had a walnut desk and a library that impressed him. He said his mother’s mother had been a second mother to him and the ‘guardian angel of his childhood.’

Older grandchildren often cared for and helped frail grandmothers and grandfathers. Their grandparents, in return, often left them a bequest. One grandfather, for example, wrote in his will, “I give and bequeathe unto my granddaughter Hubbard … one cow [named] Primrose.”

But grandchildren didn’t always get to choose whether they’d take care of Nana and Papa. Under the law, families had to take care of poor relatives; parents and grandparents had to take care of the children; adult children had to take care of their parents and grandparents. Colonial records show officials warning young adults to take care of their parents.

And so clergymen took on a task they hadn’t had before New England invented grandparents. They had to exhort their parishioners to respect their elders.

With thanks to Colonial America to 1763 by Thomas L. Purvis. This story was updated in 2023.

1 comment

While it is generally accepted that people didn’t live as long as we do today, it wasn’t as unusual as this article suggests, to have three or even four generations of a family living in a village at the same time. Many of my own ancestors in the C18th would have known some of their grandparents and some would have known great uncles and aunts too.

Longevity wasn’t that unusual, but the average age of death was so low because of the high number of infants and children who died, as well as the number of women who died in childbirth.

Comments are closed.