Among his many accomplishments, which include founding Quebec City and mapping New France, Samuel de Champlain started a war.

Born into a family of mariners in 1567, Champlain began exploring North America in 1603 with his uncle, Francois Grave DuPont. Five years later, Champlain received the assignment to establish a colony in Canada.

In the process, Champlain started a war with the Mohawks, part of the Iroquois Five Nations. By doing so he unintentionally drew the French into armed conflict with the Iroquois Five Nations. And he undermined French efforts to colonize New France.

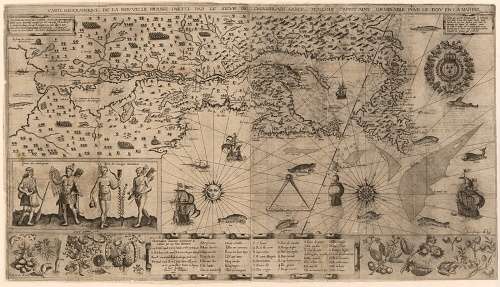

New France

At the beginning of the 17th century, the French kingdom wanted to become an empire. After seeing the success of Spanish and Portuguese colonization, the French monarchy sought to plant roots in the Americas.

French navigators had begun exploring eastern Canada in the previous century. But those expeditions comprised small groups of men seeking to establish trading relationships with the Native Nations.

To make the most of the nascent fur trade, the French monarchy decided to begin building permanent settlements in Canada. They called the territory New France. To try and save the Crown money, they granted a prominent trader named Pierre Dugua de Mons a monopoly over the Canadian fur trade. In 1608, de Mons assigned Samuel de Champlain the task of establishing a colony and extending France’s trading network.

Champlain Arrives

Arriving in Canada in 1609, Champlain found a land in the midst of increasing turmoil. Over the past century, European diseases had preceded the French colonizers.

Suffering staggering population losses of 50 percent or more, Indigenous societies were gripped by despair and population crisis.

“The advent of Europeans in the Northeast in the early sixteenth century quickly upset the existing equilibrium and transformed it into a world of disease, division, violence, and death,” wrote historian Georges E. Sioui.

The Mourning Wars

The Iroquoian peoples of the Northeast sought to rebuild their populations by adopting outsiders into their society. They often brought newcomers in as captives from battle — a phenomenon known as a Mourning War.

Forcing captured adoptees to abandon their old identities and take up new ones to fill a void in their new society could be rather violent. But the Mourning Wars served their purpose of stabilizing Indigenous societies.

After Europeans and their pathogens arrived, however, the Mourning Wars grew in frequency, scale and violence.

Iroquoian raiders attacked other nations in the Great Lakes, Canada, New York and New England. They made it as far east as the Abenaki, whose homelands stretched across Maine and the Canadian Maritimes.

Champlain hinted at the increased warfare the country had seen. On a journey from Quebec to Mohawk territory, Champlain “saw four beautiful islands… which, like the Iroquois river, were formerly inhabited by Indians: but have been abandoned, since they have been at war with one another.”

The March to Lake Champlain

In the early stages of their Canadian colonization, the French aligned themselves with the Wendat, an Iroqouian people living in what is now southern Ontario. They also allied with several Algonquian peoples, such as the Montaignais.

Champlain hoped to use these alliances to expand France’s fur trading networks. Reflecting back on these alliances in 1619, Champlain wrote: “I came to the conclusion that it was very necessary to assist them, both to engage them the more to love us, and also to provide the means of furthering my enterprises and explorations [fur trading] which apparently could only be carried out with their help.”

To strengthen New France’s bond with these nations, Champlain agreed to accompany them on a raid on the Mohawk Nation. So he and nine other French soldiers joined a group of Wendat, Montagnais and other Algonqian warriors into Mohawk lands, which stretched from eastern New York into western Vermont.

The company tried their best to conceal their movements by traveling from Quebec to the Mohawk lands at night. Despite their attempts at stealth, Mohawk scouts kept track of their movements. A Jesuit chronicler of Champlain’s exploits later noted the Iroquois always had “sentinels upon the routes of their enemies.”

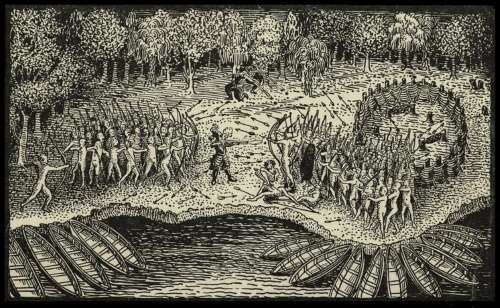

Finally, 200 Mohawk soldiers confronted the group on the shores of Lake Champlain.

The Shot Heard ‘Round New France

The two war bands now stood within earshot of one another. They exchanged insults and built fortifications. Seeing how their enemies had “barricaded themselves well” farther down Lake Champlain’s shore, the French and their Native allies agreed to postpone the fight until the next day.

The next day, the two forces came out to meet each other. According to Champlain, he led the charge, marching toward the Iroquois line until he was within some 30 yards of the enemy.

Champlain then claimed he drew his firearm and took aim at the Iroquoian leaders. “With this shot,” Champlain wrote, “two fell to the ground and one of their companions was wounded who died thereof a little later.”

While Champlain’s recounting of the event tells some truths, he was most likely exaggerating his role as a leader. The Jesuit Relations, a collection of letters written by French missionaries, temper Champlain’s telling of the battle.

According to the Jesuit Relations, Champlain had wanted to advance” toward the men perceived as the leaders of the Mohawk contingent. His Native allies, or “Kebec savages” as the Jesuits put it, prevented him. They told him to “withdraw behind our first rank, and when we are ready, thou shalt advance.”

No matter where Champlain stood when he fired his arquebus, however, he does seem to have killed several Mohawk warriors.

The Implications

Whether or not the Mohawk men Champlain killed occupied an important political role in their villages, by taking their lives Champlain started a war.

The hostile Iroquoian relations with New France also indirectly fanned the flames of the Mourning Wars. The Iroquois continued to lose population as they increasingly engaged in armed conflict with Europeans.

As a result, the Iroquois carried out more raids against their Native foes, hoping to capture enemies to balance out the loss of life. By the 1660s, contemporary European sources claimed that some two-thirds of the Iroquois population were foreigners adopted into Five Nations society.

Due to these raids, by the late 17th-century, Iroquois holdings ranged from New England’s western frontier to the Ohio River Valley.

Ultimately, the increased range and violence of the Mourning Wars destroyed the sovereignty of several Native Nations. The Wendat and Abenaki diaspora spread in several directions.

The Iroquois Five Nations survived the Mourning Wars and became the strongest Native Nation of the Northeast. But the demographic upheaval of the 17th-century left them unable to defend their sovereignty in the 18th.

In 1609, the French-Canadian population spread from northern Maine to the interior of Ontario and Quebec. However, it was sparse at best. Since Champlain started a war that continued into the 18th century, it made it harder to convince French subjects to settle in New France.

Additionally, it led the Iroquois Five Nations to make alliances with the Dutch in New York and the British in New England.

The author of this story, Jordan Baker, holds a BA and MA in History from North Carolina State University. A lover of all things historical, he concentrates his research and writing on the history of the Atlantic World. He also blogs about history at eastindiabloggingco.com, where he has also written about the Mourning Wars.

This story updated in 2023.