Margaret Fuller, who spent her life protesting injustice, died at the age of 40 in a shipwreck off New York Harbor while onlookers watched from the shore.

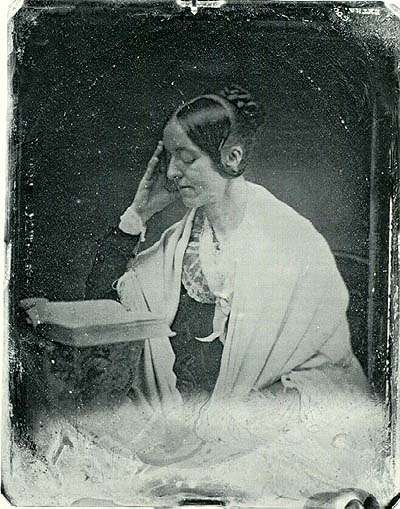

She was America’s first feminist, first female literary critic and first woman foreign correspondent. She was known as the best-read woman in New England (and therefore probably the country).

Margaret Fuller was friends with Ralph Waldo Emerson and edited his transcendentalist magazine, The Dial. Nathaniel Hawthorne based Hester Prynne on her. Edgar Allan Poe called her a ‘high genius’ – also a busybody. She was bitchy and witty; also poor and often ill.

When the year 1850 started, Fuller wrote to a friend: “I am absurdly fearful and various omens have combined to give me a dark feeling … It seems to me that my future upon earth will soon close … I have a vague expectation of some crisis—I know not what.”

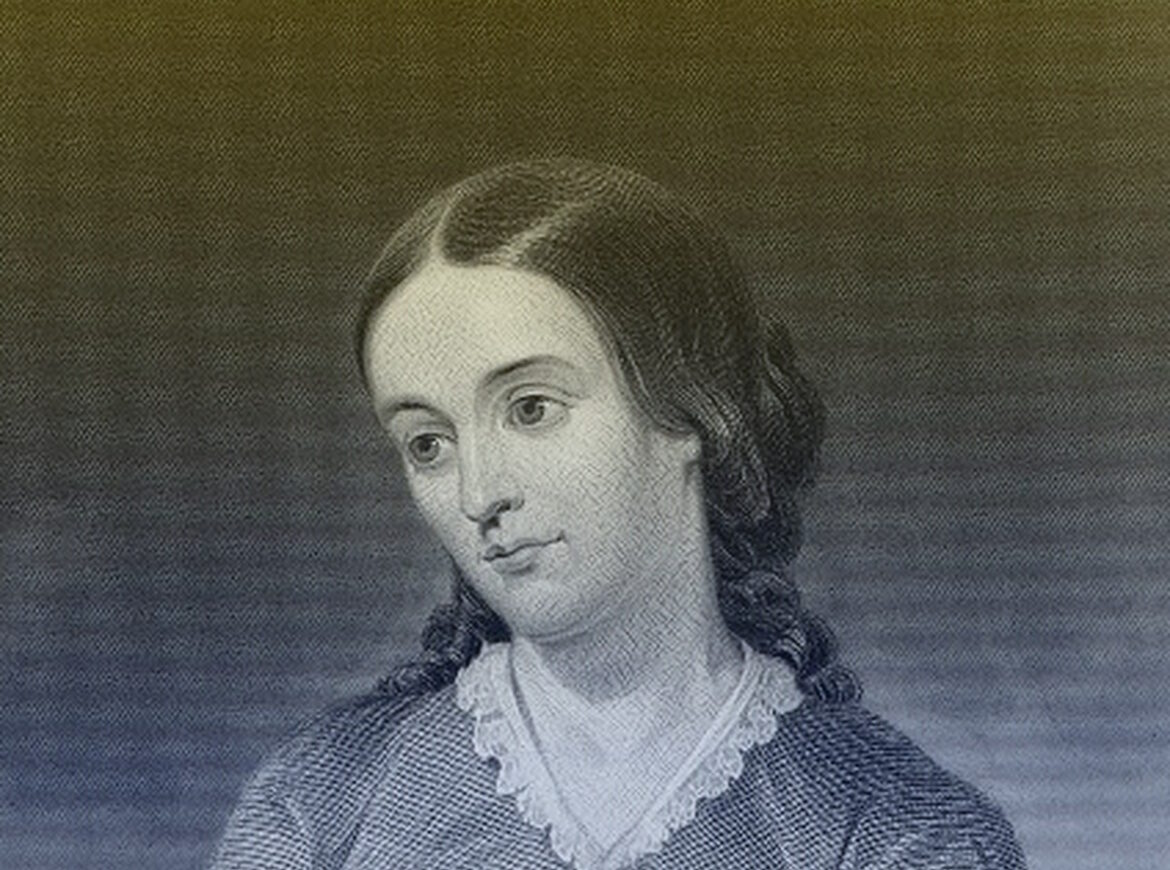

Margaret Fuller

Sarah Margaret Fuller was born in Cambridge, Mass., on May 23, 1810, the daughter of Timothy Fuller and Margaret Crane Fuller. Her father taught her to read and write before she was four.

She taught school, wrote literary criticism and edited The Dial. She wrote Woman in the Nineteenth Century, considered the first book on American feminism.

Horace Greeley hired her to write literary criticism for the New York Tribune. He sent her to England in 1846 as a foreign correspondent.

While in England she met an Italian revolutionary, Count Giovanni Ossoli, 10 years her junior. They became lovers and she became pregnant. Together they went to Rome, where he fought for a democratic Rome against the French and Austrian armies.

Margaret Fuller cared for wounded soldiers until her pregnancy prevented her from doing it anymore. When the revolutionaries lost Rome, they moved to Florence. Ossoli’s parents cut him off for his involvement with a Protestant and his revolutionary activities. Whether he ever married Margaret isn’t known.

She bore a child, a boy named Angelino, and wrote an eyewitness history of the Roman revolution. But the family’s financial outlook was grim. She couldn’t support herself or her family in Italy, so she decided to return home.

The Elizabeth

Emerson offered to buy her a ticket home, but she refused. She booked passage on the freighter Elizabeth out of Livorno on May 19, 1850. It was loaded with blocks of Carrara marble, including a bust of John Calhoun. The ship rode so low in the water her friend Robert Browning advised her not to go when he saw her off.

During the voyage the captain died of smallpox and Angelino contracted the disease. She was relieved when he recovered, but the worst was to come.

The inexperienced first mate who replaced the captain thought the Fire Island lighthouse was the Navesink Light off Cape May, N.J.

As the Elizabeth approached the coast on the night of July 19, a gale hit. The mate should have sailed along the shore, but instead he sailed into it.

The Elizabeth hit a sandbar with a jolt at 4:10 a.m. Passengers woke by the sound of the ship’s hull splintering against the sand. The great blocks of marble began crashing through the hull.

Nothing But Death

The passengers, a half dozen of them, crowded into the forecastle in their nightclothes and waited for dawn. Margaret Fuller, clutching her baby, could see how close they were to land.

Every wave lifted the forecastle roof and washed over the passengers. A crowd gathered on shore, watching the helpless passengers. A wave washed Ossoli overboard.

The American Shipwreck Society tried to rescue the passengers, but the roiling sea too much to bring a boat out. They tried to fire a mortar, but failed.

Margaret Fuller, drenched in a white nightgown, finally relented and gave her baby to a crewmember. He grabbed a spar, jumped into the ocean and drowned along with Angelino.

The tide rose as noon approached. At 2:30 the gale increased, the Elizabeth broke apart and by 2:45 nothing could be seen of the ship..

Margaret Fuller, sitting with her back to the foremast her hands on her knees, was washed overboard. The last words anyone heard her utter were, “I see nothing but death before me–I shall never reach the shore.”

Thoreau

Emerson sent his friend Henry David Thoreau to Fire Island to find out what happened. He recovered Fuller’s desk, some baby clothes and some papers. Her body was never found, nor was her history of the Roman Revolution. He found a coat belonging to Count Ossoli, ripped off a button and took it home.

Thoreau was shaken by the experience. “Our thoughts are the epochs of our lives; all else is but as a journal of the winds that blew while we were here,” he wrote.

He commented years later on an Italian ship wrecked, her cargo of rags, juniper berries and bitter almonds strewn on the beach. It seemed hardly worthwhile, Thoreau wrote, to send to the Old World for bitters.

“Yet such, to a great extent, is our boasted commerce; and there are those who style themselves statesmen and philosophers who are so blind as to think that progress and civilization depend on precisely this kind of interchange and activity–the activity of flies about a molasses-hogshead,” he wrote.

Three of Margaret Fuller’s friends — William Henry Channing, James Freeman Clarke and Emerson — wrote a book about her, The Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli. It was a flattering portrait that left out her illegitimate child, but it was the best-selling book in the United States until Uncle Tom’s Cabin came along.

Julia Ward Howe worked to erect a memorial to Margaret Fuller on the Fire Island shore in 1901. It washed away in a storm.

This story was updated in 2023.

4 comments

[…] handed a shipwreck to the owner of the schooner Nancy during a storm off the New England […]

[…] portraits a day. He painted one famous likeness of Timothy Fuller, a Massachusetts congressman and Margaret Fuller’s […]

[…] magazine. She also befriended Transcendentalist writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Margaret Fuller. Whitman died in 1833, and she moved back to Providence to live with her mother and […]

[…] transcendentalists such as Henry David Thoreau and Louisa May Alcott Emerson also helped promote Margaret Fuller, and in some cases supported her […]

Comments are closed.