Maine was at the center of one of the biggest boxing scandals of all time. In a sport known for its chaos and corruption, not much has ever topped the heavyweight championship fight between Charles “Sonny” Liston and Muhammad Ali in Lewiston, Maine, on May 25, 1965.

The furor over the fight started the year before, in February 1964 in Miami. That’s where Liston, the toughest fighter of his day, didn’t come out for the seventh round of his fight against Ali, then still going by the name Cassius Clay and a brash, emerging superstar.

It had been a rough bout through six, with Clay at one point claiming Liston had tried to blind him. Rather than continue, Liston threw in the towel, sitting on his stool and declining to answer the bell – a decidedly uncharacteristic decision for a fighter known for his ability to take a punch or 50.

The fight’s outcome shocked the sporting world. The media was full of conspiracy theories. One story held that Liston threw the fight. Another that he was supposed to throw it in Round 1, but did not, holding out through six to alter the eventual payouts and then quitting on his own terms.

Two Paydays

None of it made much sense, but it soon leaked out that Liston had a clause in his contract that gave him the right to manage and promote a rematch with Clay, if Clay won. That would turn one payday into two. Such clauses were against the rules of the World Boxing Association, the hapless organization under which the two men fought.

The WBA suspended both men. But promoters had to deliver a fight. Television wanted it. Clay wanted it. Liston wanted it. And the mob wanted it.

The venue had to be in a state that was willing to buck the WBA, and the fighters announced a fight for the fall of 1964 at Boston Garden. Massachusetts Gov. Endicott Peabody approved it, and the excitement was palpable.

Liston announced that he had an injured shoulder before the Miami fight and simply couldn’t throw any more punches. While his head was clear, he could not have continued to compete, he said. That’s why he quit. This time, he assured, would be different.

Liston set up training camp in Plymouth, Mass., at the White Cliffs summer resort. He charmed the people in town. He lost weight and looked in far better shape than he had in Miami. One thousand people showed up to watch his final sparring session. The public’s sympathy (and the Vegas odds) were with Liston, who was now in his 40s.

Name Change

Clay, meanwhile, was creating a circus. He announced his name change to Muhammad Ali (after first changing to Cassius X) and his affiliation with the Nation of Islam. By this point, the Nation was torn by the split between Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad. Ali had dropped his friendship with Malcolm and sided with Muhammad. Ali was busy stoking the black power movement, and training in Miami.

Boxing analysts were wondering if Ali was taking the rematch too lightly, and boxing fans were eagerly awaiting the November bout. Liston, who had a criminal past and lots of ties to the mob, suddenly found himself in the unusual position of being the public’s favored choice over the caustic Ali.

The Massachusetts fight would not take place, however. Ali suffered a hernia during training and had to be hospitalized. The surgery would prompt a six-month delay of the fight.

Muhammed Ali in l ewiston

As 1964 turned to 1965, the hype over the fight only grew. Malcolm X was assassinated by members of the Nation of Islam. John Volpe, the newly elected governor of Massachusetts, had no love for the fight that his predecessor had sanctioned. He had concerns about the violence enveloping the Nation of Islam and Ali growing more controversial by the day. Liston, meanwhile, had another scrape with the law, turning the fight into a black eye for Massachusetts.

By now, the racial overtones of the fight took on a life of their own. Ali made fun of Liston’s appearance, poking him as “the bear.” The NAACP had been wary of Liston because of his criminal past and ties to the mob, but Ali was even scarier for his much more outspoken views on race. Meanwhile, within the Nation of Islam, Ali was controversial. Boxing was not viewed as a proper sport for black men by the Nation, until Elijah Muhammad changed his tune. He decided that Ali’s star power and ability to deliver followers overrode the ways in which boxing offended Islamic principles.

Meanwhile, with a television contract to fulfill and not a lot of boxing people happy with either Ali or Liston, the fight promoters had to scramble to find another venue after Massachusetts officials got cold feet. They found an unlikely home at St. Dominic’s Arena in Lewiston, Maine. The media moved in to the state for the fight and Liston set up at the Poland Springs Resort.

Rumors and Threats

Rumors abounded that followers of Malcolm X intended to kill Ali in retaliation for Malcolm’s murder. The Nation of Islam, meanwhile, had threatened Liston, he reported. Security was exceptionally tight the night of the fight. The preparation was so rushed the arena wasn’t even close to a sellout. Only 2,400 tickets were sold, and as it turned out some people hadn’t even gotten to their seats before it ended.

Late in Round I, Liston inexplicably collapsed to the canvas, the result of the famous “phantom punch.” Ali screamed at him to get up and taunted him. Liston did rise up to one knee. Referee Jersey Joe Wolcott could not keep Ali confined to a neutral corner and lost control of the count. Liston collapsed back to the canvas to wait longer, then he stood up again. With that, the fighters again began throwing punches.

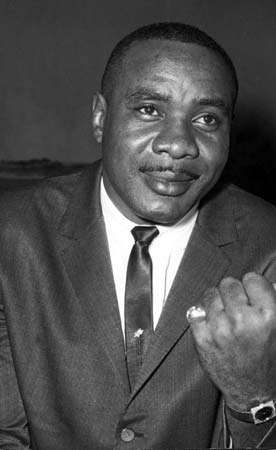

Probably the most famous picture taken of Muhammed Ali.

Wolcott, however, stepped in and stopped the fight. Even though the fight restarted, Wolcott declared he’d counted out Liston and Ali had won. Ali believed Liston had thrown the fight, and said as much to his manager. He simply had not hit him hard enough to knock him out. He wasn’t sure he had hit him at all, he said at the time. His manager disagreed and convinced him he had won fairly. You can make up your own mind by watching the entire fight here.

Was there a phantom punch? Had the Nation of Islam intimidated Liston into taking a dive? Was it just a case of an old fighter overmatched by a young one? No one will probably ever know for sure, though it seems the most likely scenario is the most obvious one: Liston quit, twice, probably at the direction of mob gamblers.

Theories About Muhammed Ali in Lewiston

Following the Miami debacle, Time magazine reported that Irving “Ash” Resnick, a mobbed-up associate of Liston’s, had lost $1 million backing Liston in the fight. Resnick was a shady former basketball player and bookie (sometime incorrectly identified as a former Boston Celtic). He befriended athletes and was one of the original promoters of Las Vegas, where he worked hard to bring celebrities and athletes to the casinos to attract star-struck gamblers.

Over the years, many observers felt the Resnick-lost-$1-million story didn’t hold water. He and Liston remained friends. Liston also kept friendly relationships with other Las Vegas mobsters, an unlikely situation if he had turned on them. Today, it looks like the skeptics were right. The FBI recently released its files on the investigation into the fight, however, and they tell a different story.

An FBI informant told investigators that Resnick at first suggested he wager on Liston in Miami. But then he called him the day of the fight and told him to keep his money in his wallet. He’d understand after the fight. The Time magazine story simply covered for the fact that Liston and Resnick had conspired to throw the fight, he said. There was more money for Liston in losing to Clay/Ali than there was in winning.

No more will likely be known about the details of either fight. Liston died in 1971, apparently of a drug overdose (though naturally conspiracy theories have arisen over his death, as well). He worked up until his death for Resnick, who would go on to serve as an executive at Caesar’s Palace casino.

And whatever questions the public may have had about Ali’s legitimacy as champ were put to rest by his long run as the biggest mouth and best fighter in boxing.

This story updated in 2022.

Image: By Slavin3232 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=113099640.

15 comments

$100 in 1965, must have been ringside!!

$100 in 1965, must have been ringside!!

$100 in 1965, must have been ringside!!

I listened to that on my transistor radio that night!

Liston took a dive forced by the mob.

holy smokes! $100 for a ticket back then! That was a week’s wager, I’ll wager…

Row A, ringside.

Wow that was expensive, especially back then!!

Wow that was expensive, especially back then!!

What they neglected to mention was that my Grandfather, Sam Michael, was the promoter who brought this fight to Lewiston! My Father was an usher that night. He saved two tickets and his brass usher badge. I now have it.

We were at the weigh in as kids. Liston’s sparing partner Night Train Lincoln mentioned he could have knocked out Listen anytime during training..

[…] and weren’t looking to make money off of him. However, in 1964 when Ali had to call off his rematch fight with Sonny Liston due to a hernia, Ali’s supporters complained about the millions of dollars they had lost due […]

[…] were among the tens of thousands of men, many immigrants, who came each year to Bangor and Lewiston, Maine. They’d spend a few days in cheap boardinghouses before shipping off to the north […]

[…] Though Rocky Marciano was always an underdog, he was the only heavyweight champion to finish his career with no defeats. Forty-three of his 49 wins were knockouts. […]

[…] Sharkey later said the fight was fixed. […]

Comments are closed.