In 1676, Richard Waldron of Dover, N.H., received an unwelcome order from Massachusetts. King Philip’s War was winding down and a group of Indian fighters had fled to New Hampshire. The government at Boston wanted them pursued and punished.

King Philip’s War pitted the Wampanoag against the Massachusetts colonists in 1675. The colonists drove the Indian forces northward until the war finally ended in 1678.

A View near Point Levy opposite Quebec with an Indian Encampment, by Thomas Davies (National Gallery of Canada)

By 1676 Waldron was something of a strongman in New Hampshire. The deputy to the Massachusetts General Court, he had served as second president of the colonial New Hampshire Royal Council.

He was an ornery Puritan who emigrated from England in 1635, Waldron came from wealth and expanded it greatly, acquiring lands in Dover where he constructed mills on the Cochecho River. He also ran an active trading post with the local Pennacook Indians, with whom he maintained largely friendly relations.

Richard Waldron

He was not to be trifled with. When two Quaker women persisted in spreading their beliefs in Dover, he had them stripped to the waist, marched behind a cart through 11 towns and flogged before setting them loose to flee into Maine.

Waldron clearly sided with the English colonists, but the order to harass the Indians – his trading partners – posed a dilemma. If he carried it out he would attack Indians with whom he had maintained peaceful relations. If he refused he would lose favor with Massachusetts.

The Pennacook, under Passaconaway and his son Wonalancet, kept a peace with the English settlers. But eventually they both despaired because the English continually ignored treaties and agreements.

Waldron ultimately found a stealthy way of eating his cake and having it too. Or so he apparently thought. He invited the Pennacook to a “sham battle” – a war game. When the Indians had discharged their muskets, he captured the fugitive Indians he sought – along with a handful of local Pennacooks – and shipped them to Boston.

Waldron may have thought he had carried out his mission with minimal violence. But the Indians thought it dishonorable.

Thirteen Years Later…

Revenge is a dish best served cold, the old adage suggests, and it certainly was for the Pennacook. For 13 years the tribe mulled the fate of Richard Waldron. Several of the fugitives he had sent to Boston were tried and executed for their part in King Philip’s War. Indians not executed were sold into slavery in the Caribbean.

Following King Philip’s War, New England enjoyed a period of peace. But tensions festered as the Indians and colonists chafed against one another. English settlers viewed the Indians as essentially a conquered people now subject to English rule. The Indians perceived themselves as an independent people who had signed a treaty with the colonists to end hostilities – a treaty that the colonists did not always honor.

In 1689, colonists in New Hampshire began sensing hints that the Indians were growing hostile. Some even shared their fears with Waldron – by this time 80 years old. He dismissed their concerns assuring them that he would know if the Indians intended to start a fight. “Go plant your pumpkins,” Waldron told his neighbors.

Meanwhile, Indians under the leadership of chiefs Kancamagus and Mesandoit amassed a force near Dover. King William’s War, fought to settle ownership of northern New England, was about to break out.

A Bitter End

In June, with the weather still cold, several Indian women asked if they might sleep near the fire inside the garrisons that the colonists under Waldron had built at Dover. This was not uncommon on cold nights, and the colonists welcomed them.

Mesandoit himself sat with Waldron one night. He informed Waldon that some Indians were coming soon with some merchandise to trade. He asked Waldron what he would do if unfriendly Indians arrived. Waldron assured him that he could rouse a force of 100 men in an instant.

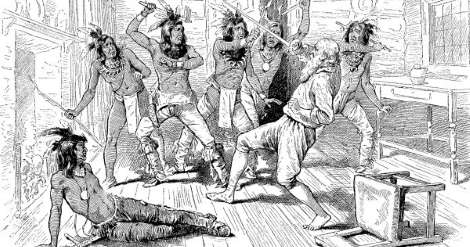

Late in the night, with the colonists sleeping and no watch posted, the Indian women inside the garrisons opened the doors and admitted the assembled Indian forces. Awakened by Indians in his home, Waldron fought furiously with his sword to repel the invaders, but he was over-matched.

Waldron’s final moments were painful and unpleasant as the Indians tortured him to death and taunted him with a final question: “Who will judge the Indians now?”

The Indians left Dover with 29 captives, which they intended to sell in Canada. Twenty-three people were killed. The garrisons and mills were plundered and burned.

Following the attack, a letter arrived for Waldron from Boston warning him than intelligence from Chelmsford, Mass. suggested some Indians were planning an attack on Dover, coming under the guise of peaceful traders.

Thanks to: The Border Wars of New England, Samuel Drake and The History of New Hampshire, Jeremy Belknap. This story updated in 2022.

3 comments

[…] had taken refuge on Aquidneck Island, rightly fearing an Indian attack. It was the midst of King Philip’s War, and Roger Williams tried to stop the bloodshed. He was 77 years […]

[…] It didn't take long before the Puritan townspeople spoke up about the newcomers. They petitioned Richard Waldron, the magistrate at Dover, "humbly craving relief against the spreading and the wicked errors of the […]

[…] it hardly ended the fighting between the persistent English colonists and the Indians (aided by the French). A new garrison was established at Black Point in 1681, near what was then […]

Comments are closed.