There’s more to Irish-American history than the Great Hunger, the Kennedys and ‘No Irish Need Apply.’ Irish Catholics came to New England along with the Puritans, who encouraged the Scots-Irish to settle along the frontier. You’ll find some of the earliest Irish landmarks radiating out from Boston — in Southern Maine and across the New Hampshire border, for example.

The Irish fished off the New England coast when New Hampshire and Maine belonged to Massachusetts. They built Catholic churches when Paul Revere was making bells, and they carved canals when John Quincy Adams was president. They ran the gamut of social class, from household servants to one of Ireland’s greatest philosophers, who lived in Rhode Island.

Then between 1815 and 1845, as many as 1 million Irish immigrants came to ‘Amerikay,’ looking for opportunity.

Today Irish-Americans concentrate in the Northeast, where one in five New Englanders claims Irish ancestry. Boston is the most Irish city in the country. Nearly half the residents of Scituate, Mass., along Boston’s South Shore, are of Irish descent.

Here, then, are six Irish landmarks, one for each New England state. If you know of an interesting Irish landmark, please note it in the comments section.

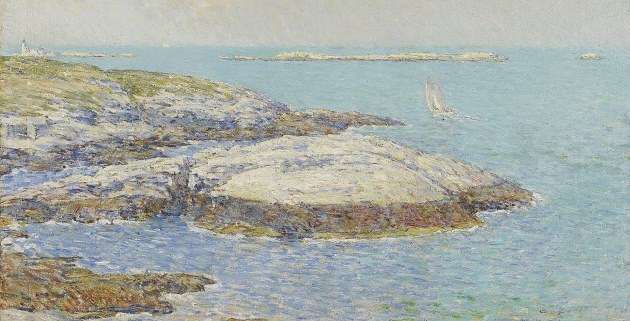

1. Isles of Shoals, N.H.

Before England destroyed Ireland’s merchant marine, Irish merchants traded with the American colonies as early as the 1630s. Irish fishermen from Galway and Waterford settled the Isles of Shoals, an archipelago of tiny islands nine miles from the Maine and New Hampshire coast.

By 1653 Europeans built a permanent settlement on the Isles of Shoals, a thriving entrepot where they caught fish, salted it and sold it on the world market. Fishermen named Kelley, Haley and McKenna lived on the islands with their families.

By 1645 as many as 600 residents lived on Hog (now Appledore) and Smuttynose Islands in Maine. When Massachusetts annexed Maine and tried to tax the Shoalers, most of them floated their homes over to Star Island in New Hampshire.

“For many years the Islands were a little kingdom and government of themselves and had a constantly increasing prosperity,” according to Michael J. O’Brien in the Journal of the American Irish Historical Society. They were a hard-drinking lot, and John Winthrop took a dim view of them.

By 1680, Roger Kelley was chief magistrate and described as “King of the Isles” and “Captain of the Isles.” Andrew Haley was described in 1680 as “King of the Shoals.”

The islanders abandoned their home during the American Revolution, and the islands developed into a summer colony for artists and writers. Childe Hassam frequently painted them.

No manmade Irish structures remain on the islands, but on a summer’s day a trip to the Isles of Shoals is a rare delight that evokes the fishermen’s past. The Isles of Shoals Steamship Co. offers several kinds of tours of the island.

2. Whitehall, Middletown, R.I.

Bishop George Berkeley had achieved celebrity as an Anglo-Irish philosopher by the time he stepped onto dry land in Newport, R.I., on Jan. 23, 1729. He came to America because he intended to open a college in Bermuda. He believed the Protestant religion had lost ground, and America was the likeliest place to make up for what went missing in Europe.

Berkeley was born in his family castle in County Kilkenny. By the time he arrived in Rhode Island, he had already established a lasting reputation as a philosopher, taken holy orders in the Church of Ireland and risen to Dean of Derry.

Berkeley and his new wife bought a farmhouse in what is now Middletown, R.I. When he enlarged the home he called Whitehall, he remodeled the door case in Palladian style, introducing Palladianism to America.

In addition to Whitehall, Berkeley left several Irish landmarks. While Berkeley awaited funds for his college to arrive, his wife gave birth to a son, who survived, and a daughter, who didn’t. They buried Lucia Berkeley in the Trinity Church yard in Newport.

Berkeley also wrote a book in America, preached at nearby churches and founded the Philosophical Society, which became the Redwood Library. Fittingly, he also wrote the poem, Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way.

Back to England

The money for his college never arrived, so he departed for England in September 1731. He gave his library and Whitehall to Yale College, stipulating the income from the property support three Yale scholars.

Yale then rented the building as an inn for many years. The portrait painter Gilbert Stuart’s grandfather ran it, once hosting Dr. Alexander Hamilton.

Whitehall was long neglected until 1899, when the Colonial Dames of America got a 999-year lease on it. They then commissioned Norman Isham to restore two rooms. Today it functions as the Whitehall Museum House, at 311 Berkeley Ave.

For information about visiting hours in the summer, call 401 846-3116 or email [email protected].

And yes, Berkeley, Calif., took its name from Rhode Island’s prominent visitor.

3. Lockwood-Mathews Mansion, Norwalk, Conn.

Irish were scattered throughout Connecticut well before the Great Hunger and even before the American Revolution. Some came as convicts or redemptioners — indentured servants. Amos Richardson, an early settler of Stonington, Conn., in 1653 wrote that a ship bringing Irish servants to Connecticut arrived in Boston. He bought four.

Irish women outnumbered Irish men. With few skills and little money, many of them became domestic servants. The money was better than in the mills, preferred by native Protestant girls who didn’t want to work in other people’s homes.

There were thousands of Irish servants in Connecticut. In 1880, the census showed 4,789 Irish-born women domestics in Connecticut; that grew to 5,571 in 1900. Almost half were younger than 25.

In 1876, a wealthy New York family named Mathews was looking for a country retreat in Connecticut. They bought a 48,000-square-foot mansion in Norwalk because they knew they could find enough servants to maintain the home. That’s because Norwalk had a Catholic Church, St. Mary’s, which attracted many Irish parishioners. St. Mary’s had been burned by Know Nothings in 1854.

The Mathews family had 10 Irish servants by 1880. They worked 10-hour days with only Sunday mornings and an afternoon off. They cleaned the floors and walls, polished silver, lit gaslights, tended the fireplaces.

The Lockwood-Mathews Mansion is now a house museum that includes renovated servants’ quarters.

The Lockwood-Mathews Mansion is at 295 West Ave., in Mathews Park, near the Stepping Stones Museum for Children.

4. Millville, Mass.

Irish stonemasons first came to the Blackstone River Valley around 1825 to build the Blackstone Canal, which linked Worcester with Providence. The last of the big New England canals, it had 49 locks along 45 miles long. By 1827, 1,000 Irish canal builders cut granite for locks, dug the trench and built the tow path.

Joseph Banigan created Millville’s Irish identity. Banigan fled the Irish potato famine and arrived in Rhode Island in 1847 at the age of eight. He left school at the age of nine, and before he turned 30 he raised enough money to found the Woonsocket Rubber Co., which made boots and shoes.

In 1877, he bought some rundown mills and water rights in Millville across the border in Massachusetts. He turned the complex into a state-of-the art mill, adding 80 new houses for workers and a schoolhouse – known as Banigan City and Banigan City School.

98 Percent Irish

Banigan hired hundreds of Irishmen to work at the mill. By some estimates, Millville was 98 percent Irish from the late 19th century to the 1980s.

By 1893 Joseph Banigan was the leading importer of rubber in the United States – and Rhode Island’s first Irish-Catholic millionaire. He sold his rubber company to the U.S. Rubber Co. cartel and became president, but didn’t last long. He started the Banigan Rubber Co. in Millville.

Banigan was ruthless toward his mostly Irish labor unions, but donated millions to orphanages, hospitals, nursing homes, schools and churches. He built Providence’s first skyscraper, the Banigan Building. Banigan died unexpectedly in 1898.

Shortly after his eldest son was born in 1900, an Irish worker named Fred Hartnett moved from Woonsocket to Millville to work at the Banigan mill. The son, Charles Leo, grew up to become a Hall of Fame catcher for the Chicago Cubs. He was better known as Gabby Hartnett.

Today, some of Millville’s worker housing can be found in the Main Street Historic District of Millville, which encompasses the village center of the town. You can hike and cross country ski to the Millville Lock along the 3.7 mile Blackstone River Greenway. A section of Rte. 122 from Millville to Blackstone is dedicated to Charles Leo “Gabby” Hartnett.

5. Arthur Birthplace, Fairfield, Vt.

Chester A. Arthur’s birthplace.

Many Irish came to the United States via Canada. They’re called two boaters, and they inspired the first presidential birther controversy.

Britain had imposed tariffs to the United States, but not to Canada, to encourage immigrants to populate the commonwealth. So empty boats that brought lumber to Britain from Canada offered cheap fares on the return trip. But Canada had few jobs and business boomed in America.

The Irish came from St. Jeans by steamboat to the Vermont communities of Burlington, Plattsburg and Whitehall. Some then moved on to Fairfield, Underhill, Moretown, Middlebury and Castleton.

Nathaniel Hawthorne described the Irish in Burlington in a travel sketch in 1835. He found them everywhere lounging around the wharves, he wrote, “swarming in huts and mean dwellings near the lake,’ and ‘elbow[ing] the native citizens’ out of work.

Fairfield, Vt., a farming community, had an unusually large Irish population.

After the War of 1812, Fairfield lost its Yankee farmers to Genesee or Ohio ‘fever.’ They gave up their rocky, hilly farms for the flat, rich land of western New York and the upper Midwest. They left behind cheap land, which the Irish had craved since the English had made it nearly impossible for Catholics to own land in Ireland. Fairfield was also near Catholic churches in southern Quebec, only two towns away.

By 1840, Fairfield’s population rose to 11.5 percent Irish. Chester A. Arthur’s Irish father came to Fairfield. The future president was then born in Fairfield in 1829. That aroused the suspicion of his political enemies. Opponents accused him of being secretly Canadian.

Click here for visiting hours to the Chester A. Arthur birthplace.

6. Neal Dow House, Portland, Maine

The waves of Irish who fled the Great Hunger in the mid-19th century faced poverty, disease and discrimination. In Portland, Maine, Mayor Neal Dow didn’t just discriminate, he attacked. Dow warred against the Irish with his temperance crusade. He had, after all, called them ‘rum-swilling foreigners.’

Dow famously feuded with an Irish bootlegger and brothel owner named Mrs. Margaret Landrigan. She called herself Kitty Kentuck. A two-boater from County Cork, she arrived in Portland in the 1840s. Her husband then left her with two sons, and she began selling liquor illegally.

Kitty Kentuck bought property in Portland, but went to jail for repeated liquor offenses from 1846-1851. Neal Dow’s estranged cousin John Neal defended her, and the two men attacked each other in the newspaper. Neal called her ‘a poor, but generous, kind-hearted Irish woman.’ Dow then countered she kept ‘a notorious groggery’ that caused police more trouble than any other.

Many Irish Landmarks in Portland

Kitty remarried, continued to bootleg and ran a sailor’s boardinghouse and brothel. Every deep-sea sailor supposedly knew the lyrics to a song about the pleasures one could find at Kitty’s. She spent time in the county jail for prostitution, and her building burned in the Portland fire of 1866. She then built a shanty where she died, presumably murdered. Police suspected Kitty’s son Michael of killing her, but never charged him.

Neal Dow’s house belongs to the Portland Irish Heritage Trail at 714 Congress St. Now a house museum (click here), it’s one of 58 Irish landmarks along the trail.

* * *

Click here to order your copy.

Click here to order your copy.

Images: Whitehall PD-US, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21354546; modern Whitehall, By JERRYE & ROY KLOTZ MD – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23611134; Lockwood Mathews Mansion By Noroton at the English language Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6199774; Millville Lock courtesy Library of Congress. Arthur birthplace By Gerald L. Hann – camera, Attribution, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37860210 This story about Irish landmarks was updated in 2024.

9 comments

[…] Redwood Library and Athenaeum started off as a 45-member literary society founded by Bishop George Berkeley, the great Irish philosopher who moved to Rhode Island in 1729 to start a college. The Company of […]

[…] 1912 had already been an adventure by most standards, and a rather pleasant one at that. She had left her native Ireland as a young woman to live with her aunt Kate in Providence, R.I. She tried different jobs, and at 24 […]

[…] of the victims had immigrated from Canada and Ireland. Most were women, children or old […]

[…] Fall River textile mills employed a large immigrant population, mostly from Quebec, Ireland and England. Like most Chinese immigrant cooks, Frederick Wong tailored his food to the taste of […]

[…] have already brought you six Irish landmarks in New England, but many of them are closed in the winter. So in honor of St. Patrick’s Day, we bring you six […]

[…] French and the Irish didn’t get along in many New England cities, not just Fall River. Most were poor Quebecois who […]

[…] low and the work extremely dangerous. A quarter of the workers were children between 7 and 16. The Irish immigrant miners had formed the Molly Maguires, who used guerilla tactics against the mine […]

[…] were illegal in 1853, but that didn’t stop Irish immigrant gangs in New York City from roughing each other […]

[…] Several surprising landmarks, for example, involved historic figures of Irish descent (not Kennedy). One landmark tells the story of working-class Irish women. Another describes a town that was 98 percent Irish (not Boston). Click here. […]

Comments are closed.