It will probably be several centuries before the Northeast United States again suffers anything like the 1965 drought. It was the driest year of a 10-year dry spell that devastated farms and sent municipal leaders into a panic over the drinking supply.

There were actually two droughts: The agricultural drought, and the water-supply drought. Farmers tried to save their crops and fed their livestock in barns, while suburbanites were told not to wash their cars or take long showers.

There was a high pollen count, high fire danger and high prices for produce. Wells dried up. Rivers, ponds and reservoirs became stinking mud holes. The air was so dry foggy mornings disappeared along the coast.

According to climatologist W.C. Palmer, the 1965 drought was “such a rare event that we should ordinarily expect it to occur in this region only about once in a couple of centuries.”

The 1965 Drought

The 1965 drought actually occurred during 1961-69, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. It began in 1960 in western Massachusetts, where precipitation was below average. Then in 1962 eastern Massachusetts dried up. The rest of the Northeast got little rain or snow.

From 1962 to 1966, 34 out of 46 months had below-average precipitation. The summer of 1964 was very dry. Overdrawn reservoirs weren’t replenished.

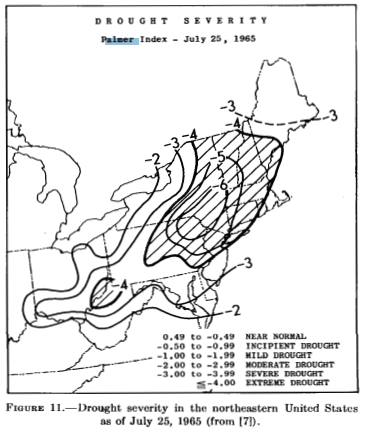

Then 1965 was the driest year on record since the late 19th century. The 1965 drought was most severe in northeastern Pennsylvania and southeastern New York. That year, Connecticut got only 29.45 inches of precipitation, far below the average of 46.15 inches. Maine was drier than in 1947, when fires destroyed nine communities and a quarter-million parched acres.

Then 1965 was the driest year on record since the late 19th century. The 1965 drought was most severe in northeastern Pennsylvania and southeastern New York. That year, Connecticut got only 29.45 inches of precipitation, far below the average of 46.15 inches. Maine was drier than in 1947, when fires destroyed nine communities and a quarter-million parched acres.

By July, communities were declaring water emergencies. Towns banned water use outside, but police and water departments were besieged by people calling to report neighbors who watered their lawns or washed their cars.

Sahara

Golf courses dug wells and dredged ponds. Fairways burnt up as watering was restricted to greens and tees. Brae Burn in Newton, Mass., “may as well be on the Sahara,” reported the Boston Globe. Brae Burn dug 20 test holes to find water. All were dry.

Part of the reservoir in Cambridge, Mass., oozed muck. In Norfolk, Mass., the 20-acre Kingsbury Pond was a stinking sea of mud. Commuters from the western suburbs in Boston rolled up their windows in summer to avoid smelling the stench of the Charles River. Usually water was discharged into the river to dampen the smell of the raw sewage that flowed into it. Not during the drought.

Herring couldn’t swim from the sea to fresh water to spawn. The Town of Pembroke, Mass., banned herring fishing and helped the fish upstream by carrying them in barrels. By fall, millions of herring spawned in fresh water couldn’t make it back to the sea in the dried-up streams. Trapped in ponds, the seagulls feasted on them.

Pastures, hayfields and cornfields were burned out by the 1965 drought. Dairy farms in Fairfield County, Conn., lost most of their pasture grass, and wells went dry for a third of them.

The honey crop in Vermont was smaller than usual. So was the blueberry crop in Maine. Shade trees, such as the Norway and sugar maple, were damaged. Along Rte. 2 between Concord and Cambridge, Mass., Red Pine needles turned brown.

Emergency

In July 1965, President Lyndon Johnson ordered a study to find out what the federal government could do to help New England. Cities and towns got loans of pumps and pipes to access the deepest arts of reservoirs. Some Massachusetts towns borrowed vintage World War II pipes from Fort Devens and Romulus Air Force Base to reach water beyond normal sources. It didn’t work. The pipe was too expensive to transport.

President Johnson

Rockport, Mass., got approval to use water from a quarry, so long as it was treated twice with chlorine. Also in Massachusetts, Randolph, Holbrook and Braintree banded together to get water from a gravel pit. Fitchburg hired a rainmaker.

The next month, 11 Massachusetts counties were declared drought disaster areas. More than a hundred Massachusetts towns restricted water. Hanover considered a moratorium on building permits. Sandy Pond beach was closed in Ayer after hundreds of dead fish floated to the surface, deprived of oxygen.

Scattered Relief

By September, some parts of New England got rain. In western Massachusetts, rain changed brown pastures to green and grass and alfalfa returning to some farms. Cranberry growers were skating by. Some reservoirs filled to capacity.

The 1965 drought eased in Northern New England except for coastal Maine. In Grand Isle County, Vermont, too much rain left standing water in fields.

Then temperatures dropped.

The water problem worsened in November because the cold locked precipitation above ground. In southeastern Massachusetts, a cold snap destroyed a quarter of the cranberry crop. Cranberry growers didn’t have enough water to flood their bogs and prevent the berries from freezing.

Test wells throughout New England reached record lows and nearly a dozen towns along the coast had to draw down their emergency supplies. On Nov. 1, 1965, the Quabbin Reservoir fell to 59 percent of capacity, a drop of 17 percent in 12 months.

Car washes, service stations and ski areas couldn’t get water.

The 1965 Drought Continues

By April 1966, the rainfall shortage increased to nearly 37 inches since the drought started in 1963, reported the Boston Globe. That almost equaled a year’s supply of rain.

People thought the drought ended with heavy rain in July and persistent fog along the coast. A dry August ended that hope.

A Boston College scientist suggested detonating dynamite, creating tiny earthquakes, could end the 1965 drought. The disturbed soils would the presence of water and suggest areas for drilling, he said.

By October 1966, farmers said the drought had ended. But the water-supply drought had not. There wasn’t enough water in wells, water tables and reservoirs.

A wet spring in 1967 ended the drought. Above normal rain and snow from February to May filled the reservoirs. On April 25, 1967, Malcolm E. Graf, Massachusetts Water Resources Commissioner, stated the four-year drought, worst in New England history, was over.

Photo: Quabbin Reservoir By Solarapex at en.wikipedia, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11535183. Cracked mud By Rosser1954 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=90076337. This story about the 1965 drought was updated in 2022.