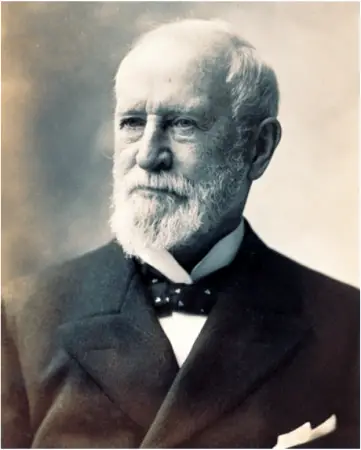

Charles Lewis Tiffany, the founder of the world-famous Tiffany & Co., came by his trade as a young man in Connecticut. Born in Killingly, his father Comfort manufactured cotton, and from time to time Charles would serve as a clerk in his father’s store.

The work appealed to him, but he also recognized the value of location in retail. In 1837 he ventured to New York City to find a far larger base of customers to sell to.

Charles Lewis Tiffany, Stationer

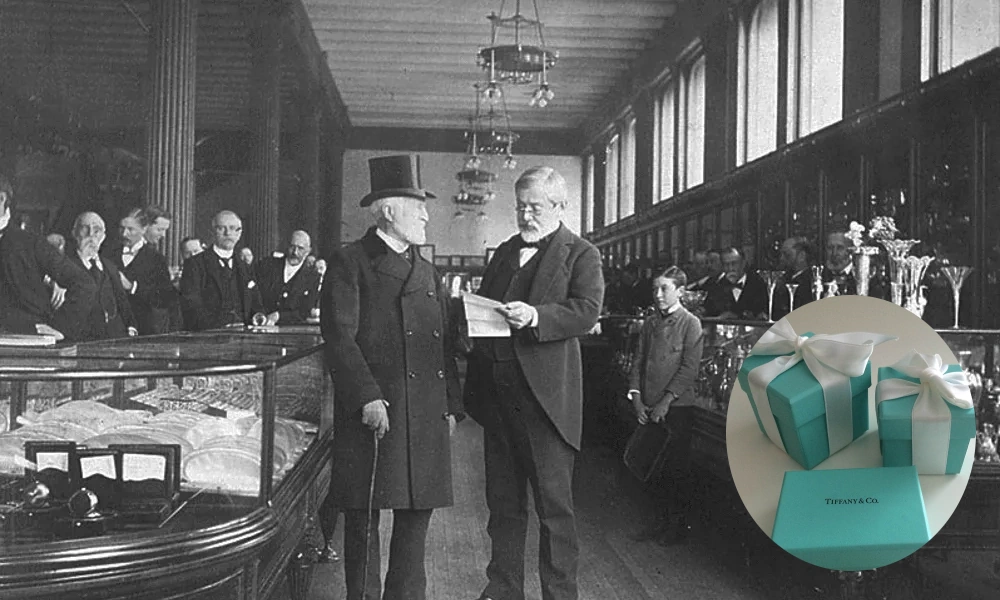

He didn’t start out as primarily a jeweler. With $1,000 borrowed from his father, he opened a stationery story, and he called it Tiffany & Young with his partner John Young. The store added gifts over time. But Charles Lewis Tiffany soon turned his focus to jewelry.

In 1841, having brought in another partner, the store name changed to Tiffany, Young & Ellis. Finally, in 1853, the final name change occurred, with the store being called simply Tiffany & Co. after the two other partners retired.

Charles Lewis Tiffany

The store became primarily associated with jewelry in the 1840s, when prices on diamonds were crashing in Europe. The company invested heavily at the bargain prices.

As the Civil War broke out, Tiffany shifted the company’s focus to selling metal goods to the military, but shifted back toward luxury goods in the peacetime that followed.

In 1845, Tiffany launched the company’s signature blue box, and put in place the rule still enforced in the stores: No employee can ever sell or give away one of the signature boxes unless it contains a gift from Tiffany.

Tiffany led a private life, largely free of any scandals. His business brought about its share of lawsuits, but his reputation was positive. He did, however, have a role – a rather embarrassing one – in a major swindle.

Great Diamond Hoax

The Great Diamond Hoax of 1872 was a fairly simple ruse. Two con men acquired some industrial grade diamonds and began showing them around as evidence that they had discovered a major diamond mine. As word spread, investors jumped aboard.

Typical of any Ponzi scheme, they took their first investors’ money, about $20,000 worth, and used it to buy more diamonds – scraps from the diamond cutting rooms of Antwerp.

The investors, eager to know exactly what they had found, sent the diamonds to Charles Lewis Tiffany for appraisal. He suggested their value was an astounding $150,000.

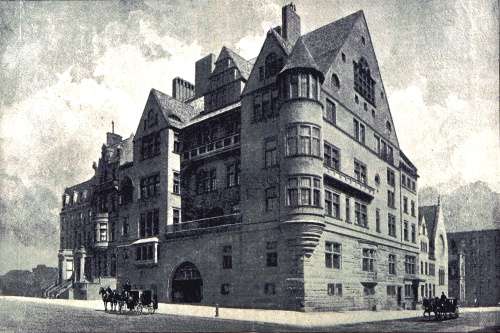

He did well for himself. The Tiffany mansion at 72nd St. and Madison Ave. in New York City.

With this new information, the investors, who now included Tiffany himself, pressured the men to sell their mine. The two crooks went to a remote spot in Colorado and salted the area with more cheap diamonds, and then brought the investors to the spot. The group of investors watched with delight as they pulled diamond after diamond from the ground.

In the end, the investors paid $450,000 for the rights to the mine. By the time a government geologist made a survey and gave them the truth, the con men were long gone.

Though the investors recovered some of their money via the courts, the incident remained an embarrassment for Charles Lewis Tiffany. It was not damaging to his store, however, which remained a symbol of luxury. By the time of his death in 1902, he was worth an estimated $35 million.

Tiffany’s

But, of course, the success didn’t end with him. His son, Lewis Comfort Tiffany, served as the company’s first design director. He earned lasting fame and a fortune, however, as an artist who produced stained glass.

The iconic store went on to be synonymous with luxury even today. It inspired the name of one of the early Bond girls from the James Bond films. Marilyn Monroe sang about it in Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend. And Audrey Hepburn brought it back to American attention with the 1961 film adaptation of Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Tiffany’s flagship store in midtown Manhattan.

A long way to stretch $1,000 invested in 1837.

This story was updated in 2022. Images: Tiffany flagship store By Ajay Suresh from New York, NY, USA – Tiffany and Co Flagship, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79704870. By AdrianaGórak – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33073626.