David Ruggles helped 600 enslaved people to freedom during the 1830s despite attempts to kill him, kidnap him and burn down his business. A free black man born in Connecticut, he ultimately paid for his courage. He suffered ill-health, character assassination and a shortened life.

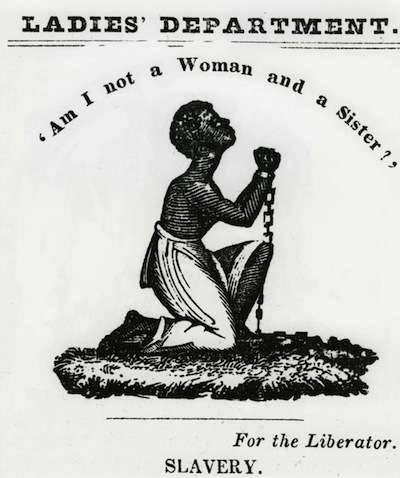

David Ruggles wrote fiery articles on the evils of slavery, antagonizing moderate abolitionists as well as slaveholders and advocates. He opened the first bookstore and published the first periodical by a black American. He printed, published, worked as an agent and sold copies of abolitionist newspapers.

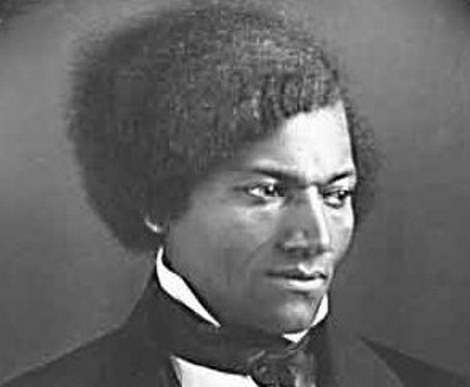

Though he mentored such activists as Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth, David Ruggles has received far less attention, perhaps because of his early death.

He defended his radical views by writing that no one could be neutral on the moral issue of slavery.

David Ruggles

Born to free African-American parents in Lyme, Conn., in 1810, David Ruggles eventually had seven younger brothers and sisters

His family moved to the elite Bean Hill section of Norwich when David was very young. David Ruggles, Sr., his father, worked as a woodcutter and a blacksmith, and his mother a celebrated cook who made fancy cakes. His devout Methodist parents had him educated at the Sabbath School for the Poor in Norwich, a religious charity school.

He was so bright as a young boy that white Bean Hill residents paid for a tutor from Yale to teach him Latin.

At 16 he moved to New York, where he worked as a mariner, a common occupation for black men. Then he opened a grocery store in an African-American enclave in Lower Manhattan. At first he sold liquor, but then he realized the damage it did to the black community. So he stopped selling it.

In New York City, he began to connect with abolitionists of all kinds — black, white, male, female, rich and poor.

And so David Ruggles became active in the temperance and abolitionist movements.

Radical Abolitionist

David Ruggles believed the printed word was an essential tool against slavery. His grocery store at 1 Cortlandt St. started to sell books, pamphlets and periodicals, until a white mob destroyed it.

He began writing for radical abolitionist newspapers and for his own pamphlets against slavery. He enraged moderate abolitionists by attacking the American Colonization Society, which aimed to relocate African-Americans to Africa.

Then in 1835 he began his most dangerous work against slavery. He and several other young black men formed the New York Committee of Vigilance, an interracial group. They put their lives on the line to free kidnapped blacks. They also attacked slavers and helped escaped slaves traveling on the Underground Railroad.

Slave catchers patrolled the streets of Manhattan then, trying to kidnap fugitive slaves or free blacks and then to send them into bondage. David Ruggles and the other members of the Committee of Vigilance confronted the slavers on the streets.

Narrow Escape

In 1836, David Ruggles heard that a Portuguese sea captain held five kidnapped Africans in his ship, planning to sell them in the South. At that time slave trading was illegal but practiced clandestinely. Ruggles obtained a writ of habeas corpus and demanded the authorities take the captives to a local jail until they had a hearing on their status.

He also got the captain arrested on charges of slave trading. Then one night the captain, free on bail, and a slave catcher knocked on David Ruggles’ door and demanded to speak to him. When he refused they tried to break down his door. David Ruggles escaped, returned with a watchman and revealed the two planned to grab him and sell him into slavery.

At that time in New York, any slave brought to the state was free after nine months. Ruggles would go to private homes to tell people they were free.

Frederick Douglass

In 1838, Frederick Douglass escaped bondage in the South, arriving in New York friendless and broke.

“I had been in New York but a few days, when Mr. Ruggles sought me out, and very kindly took me to his boarding-house at the corner of Church and Lespenard Streets,” wrote Douglass. He noted David Ruggles was ‘watched and hemmed in on almost every side,’ but ‘he seemed to be more than a match for his enemies.’

Frederick Douglass

David Ruggles put up Frederick Douglass for a few days and helped him bring his fiancée to New York so they could marry. They wed in his parlor.

The Darg Affair

When Douglass showed up in New York, David Ruggles was enmeshed in a furious controversy involving a slave owner along with two other radical abolitionists, Barney Corse and Isaac T. Hopper. Virginia slaveholder John P. Darg had arrived in New York City with his slave, Thomas Hughes. Hughes came to Hopper’s house asking for help, but Hopper said no. The next day, the New York Sun reported that Hughes stole about $7,000 from Darg.

Corse and Ruggles urged Hughes to return the money, but insisted he should remain free. But Hughes had given or gambled away some of the cash. He returned what he had left to Darg, who then had Corse and Ruggles arrested for grand larceny. Though Ruggles only spent two days in jail, the press trashed him. A cartoon appeared, called ‘The Disappointed Abolitionists,’ suggesting the three had only wanted the reward money.

Moderate abolitionists, fed up with Ruggles’ radicalism, drove him out of the movement. He had written a story in an abolitionist newspaper that a black innkeeper was helping slavers. The infuriated innkeeper sued the newspaper for libel and won a judgment of $600.

The newspaper owner, nearly bankrupted by the fine, began a print campaign against Ruggles. He demanded an accounting of the Committee of Vigilance’s books. When an audit showed $400 missing, David Ruggles had to resign his position with the committee.

Abolitionist Utopia

At just 28 years old, David Ruggles’ crusade against slavery took a heavy toll on his health. He had nearly gone blind and suffered severe bowel problems. A prominent white abolitionist, Lydia Maria Child, invited him to join an abolitionist utopia in Florence, Mass.

The Northampton Association of Education and Industry centered on a community-owned and operated silk mill. Its members sought to create a society in which ‘the rights of all are equal without distinction of sex, color or condition, sect or religion.’

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth belonged, and Frederick Douglass often visited.

David Ruggles moved to the Florence utopia in 1842. Within 18 months he recovered some of his health through the then-popular water cure, or hydrotherapy. He began studying hydrotherapy, then practiced it on wealthy members of the utopia as well as on William Lloyd Garrison.

The utopia disbanded by 1846, but David Ruggles stayed in Florence running his own hydrotherapy hospital. His health, however, declined rapidly in late 1849. He died on Dec. 18, 1849, not yet 40 years old.

This story was updated in 2022.