On July 24, 1874, a Friday, schoolteacher Marietta Ball left her St. Albans, Vt., school at 3:30 in the afternoon. She planned to walk a wooded path to a friend’s house. She often spent the weekend and Sabbath with Foster Page before returning to Mrs. Abel’s boarding house for the week.

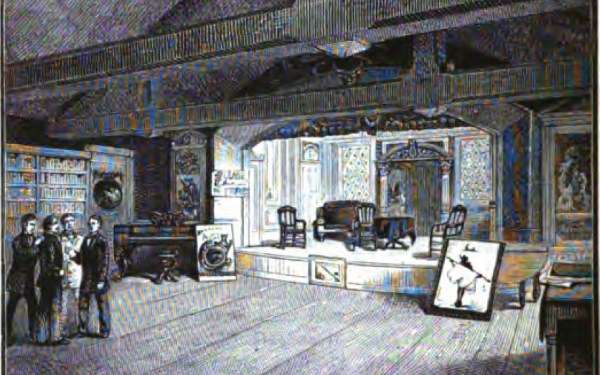

Illustration from The Trial of Joseph LaPage, the French Monster.

So no one in St. Albans was alarmed when Marietta didn’t show up at her boarding house. And when she didn’t arrive at Foster Page’s house on Friday, he didn’t worry either. She often stayed in town and came later to attend Sunday services. But he made inquiries the next day and soon the people of St. Albans found out their school teacher had gone missing.

A search party set out to locate Marietta, and found her lifeless body in the woods along the path to Foster Page’s house. “Her head was mangled as if beaten with stones and the evidence of outrage to her person was unmistakable,” the newspaper reported.

Rewards and a Manhunt

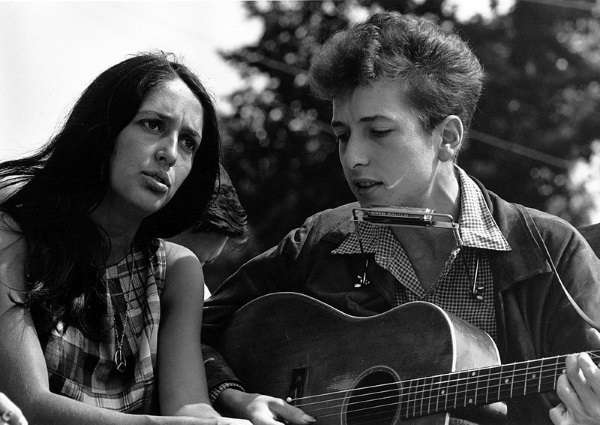

Marrietta Ball from The Trial of Joseph LaPage, the French Monster

The murder of 20-year-old Miss Ball incensed the town of St. Albans. Immediately a $3,000 reward was offered to anyone who could identify the murderer.

Suspicion fell on a burglar from Boston who robbed a jewelry store in Richmond, Vt., but nothing connected him to the crime.

The town was also reeling from a second murder. Two strangers had accosted and stabbed Joseph Minard, a young man passing through from Holyoke, Mass., to his home in Canada.

Two detectives worked to find out the truth. But as the weeks passed, the case grew colder. The detectives’ bills mounted, approaching $300 by November, and still they hadn’t identified the murderer.

Two hundred days after Marietta Ball’s murder, a St. Albans minister led his congregation to the site where her body was found. And with the winter wind blowing he preached his sermon surrounded by trees draped in black crepe. He urged his congregation to look after their fellow citizens. By May, the reward had been upped to $6000.

A Governor’s Son

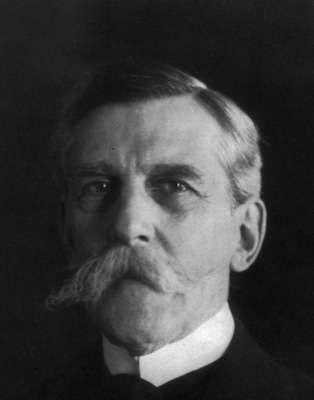

Soon gossip began pointing to one young man in town, George Gregory Smith. George Smith’s powerful father, J. Gregory Smith, had served as a senator and governor of the state. His family holdings included a rail car manufacturing factory and he was president of a railroad. He had the means to cover up a murder committed by his son.

J. Gregory Smith

Stories began circulating: George Smith had attended a dance at the hotel in Bakersfield, and he had insulted Marietta Ball there. People had seen him visiting at her boarding house. Someone had seen a coach and team of horses on the night of Marietta’s murder near the crime scene, and could identify it as George Smith’s. One of the detectives in the case had supposedly mentioned his certainty that George Gregory Smith was involved in the murder of Marietta Ball.

The rumors infuriated Smith. In July of 1875, almost exactly one year after the murder, he demanded a public hearing. Witness after witness was called. All had heard the stories about George Smith, but one by one witnesses refuted them. He had not insulted Marietta Ball at a dance (he hadn’t even attended). He had not visited her boarding house. And the person who reported seeing the coach and team of horses said she could not identify who it belonged to. Finally, the detectives in the case told the packed town hall hearing that they had never said they believed George Gregory Smith murdered Marietta Ball.

Another Murder and a Clever Detective

Josie Langmaid from The Trial of Joseph LaPage, the French Monster

With George Smith’s name cleared, at least for the time being, the detectives went back to work on their case. Still, the murder of Marietta Ball might have gone unsolved but for a gruesome discovery on Oct. 4, 1875. That morning, the body of Josie Langmaid was discovered in the woods of Pembroke, N.H.

Josie Langmaid, 17, lived in Pembroke and attended Pembroke Academy. She had left her home at about 8:30 a.m. and headed off on her regular path to school. But she never got there. Along the way, someone attacked her ferociously. When the townspeople found her, they were stunned. She was assaulted and beaten badly, her head cut off. And her face bore the marks of what doctors thought was a heel strike from a boot. The town erected a memorial to Josie that still stands today.

At first, the town suspected a neighbor of attacking Josie. Bill Drew was a layabout. A story circulated that Josie had told her teacher that Bill Drew had “grossly insulted” her. He threatened to kill her and cut her into pieces if she told her father. Bill Drew was arrested, for fear he would flee. But a sharp-eyed detective had a hunch. The attack on Josie Langmaid struck him as suspiciously similar to the attack on Marietta Ball. He began piecing together evidence.

Link to the Marietta Ball Murder

Sure enough, he found that a man linked to the Marietta Ball case named Joseph Lapage now lived in Suncook, N.H. Detectives had detained and questioned Lapage in the Ball murder. He had lived in St. Albans at the time, but they could make no case against him.

In Suncook, Lapage “was known as a sort of wandering crazy person, yet he knew many persons there and frequently chased young girls.”

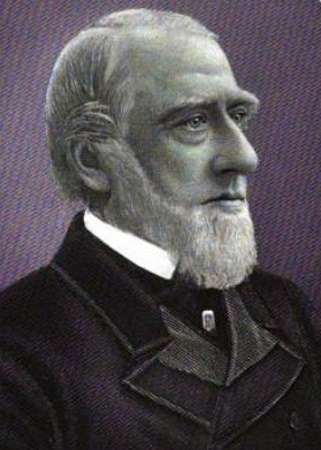

Joseph Lapage from The Trial of Joseph LaPage, the French Monster

Police arrested Lapage and searched his home. The search turned up an ax and a razor. Doctors identified human blood on some of his belongings.

The French-speaking community in New Hampshire took issue with the arrest. No one witnessed the crime, and some suspected police targeted Lapage because of his French Canadian origins. Coverage of the crime was coarse and xenophobic, with the media branding him “The French Monster.” Some may have even tried to clumsily cover for him.

But over the course of a nine-day trial in a packed Concord, N.H. city hall, an ugly story spilled out. Lapage originally came from Joliette, Quebec. There he had a troubling history. He had departed Canada shortly after his sister-in-law accused him of raping her. He had attacked and raped a cousin in Vermont, and even tried to attack his daughter, but his wife intervened.

His behavior patterns in Pembroke eerily resembled those in St. Albans. He stalked girls, asking where they lived, how they traveled to school and whether they had boyfriends. He carefully observed their movements so he would know just when to strike.

The Trial

After some legal wrangling over how much of his history prosecutors could use against him, a jury convicted Lapage of murder.

One observer of the trial came all the say from St. Albans. He noted: “We wanted to lynch him and sure it would have been a lucky thing for this other unfortunate girl, Josie Langmaid, if we had only hung him up on a tree to feed the crows and buzzards.”

Joseph Lapage had no more victims after Josie Langmaid. The State of New Hampshire hanged him in 1878.

Thanks to: The Trial of Joseph Lapage, the French Monster. This story was updated in 2023.