New England Patriots history began with an unlikely cast of characters, a decade of homelessness and an early success followed by years of losing seasons.

The team had to compete with high school and college teams for fans and with elementary school students for practice time. Patriots owners plucked their star player from a tavern in Minnesota. And when the team finally did get its own stadium, the toilets didn’t work and the Patriots didn’t even play the first game.

Perhaps it was the team’s haplessness that inspired a joke:

Q. Why doesn’t Connecticut have a professional football team?

A: Because then Massachusetts would want one.

Foolish Club

Billy Sullivan, a 45-year-old sports flack, had put out so many press releases that sportswriters called him the “Maitre de Mimeograph.” Sullivan desperately wanted to bring professional football to Boston. The NFL rejected his request for a franchise in 1959 because five pro teams had already failed in the city.

In 1936, the Boston Redskins had won the NFL championship, but the fans had so little interest owner George Marshall moved the game to the Polo Grounds in New York. The next year Marshall moved the team to Washington.

Sullivan believed New England had an appetite for professional football. After all, Boston College sold out Fenway when it won the national championship in 1940.

In late 1959, American Football League cofounder Lamar Hunt called Sullivan. He told him if he could get $250,000 in a Dallas bank within five days, he could have the final AFL franchise.

Sullivan found nine other investors, including former Red Sox star Dom DiMaggio, to put up $25,000 each for a team. The Patriots became the eighth team in the AFL. The owners called themselves The Foolish Club.

Early New England Patriots History

The team opened for business in three rooms on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston.

Sullivan held a name-the-team contest, and The Minutemen won. Patriots came in second, but the team’s advertising agency thought The Minutemen too long. So Sullivan held a second phase, an essay contest. Bill Orenberger, superintendent of the Boston School Department, judged the essays. The Patriots won, and the team went all out with the red-white-and-blue colors. Their first practice field was in Concord, Mass. Their phone number was Copley 2-1776.

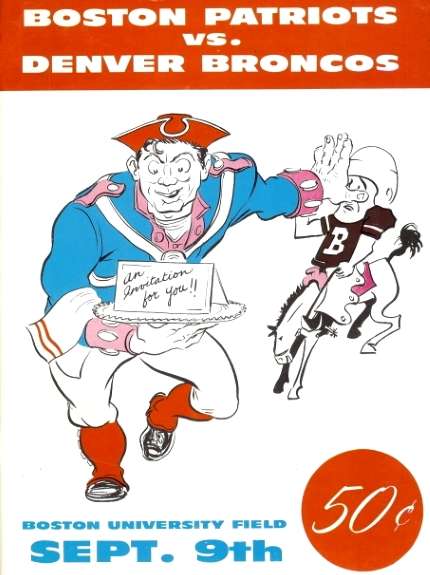

For awhile their logo was a three-cornered hat. One day the Boston Globe published a cartoon of a Revolutionary War soldier hunched over a football – Pat Patriot. One of the Sullivan children said that was the logo they ought to have.

Not the Giants

The Boston Patriots were short of everything – money, stadiums owners and fans.

In early New England Patriots’ history, the team had to vie with the New York Giants for fans. The Giants in 1960 perennially contended for championships with legendary players like Sam Huff and Frank Gifford. New England fans had watched them on television every Sunday for years. Once the NY Football Giants Fan Club of New England had hundreds of members.

The one thing the Patriots weren’t short of was wannabe players.

Lou Saban, the Patriots’ first coach, held tryouts in Boston. Saban said,

We had bricklayers, we had carpenters, we had stoker men, and you name it, we had it. We had 125 helmets in one tryout camp and we put a head in every helmet.

The inaugural training camp was held at UMass-Amherst. Fullback Larry Garron remembered,

…the turnover in that camp was like a nightmare. You would wake up in the morning and there was a different guy sleeping in the bed next to you than there had been when you went to bed the night before.

There were so many men in training camp Saban couldn’t tell them personally when he cut them. Gino Cappelletti remembered the players would run like hell after practice to the dorm to see if they’d been cut.

“A lot of guys who were cut stuck around a few days, eating three square meals and sleeping there.”

Cappelletti had been working at a bar called Mack and Cap’s in Minneapolis when a former teammate at the University of Minnesota told him about the new league. Cappelletti was playing for a team representing the bar in a touch football league. He called coach Lou Saban and – eventually – made the team.

Cappelletti played 10 years for the Patriots becoming the team’s leading scorer with 1130 points. He did it all — kicking, receiving, defending. After he retired from football he became a radio announcer, a fixture with the franchise for more than 50 years.

Finally, Fans

The team practiced at local schools. Saban remembered one practice in Lexington, Mass.

We were out there in our pads and doing our drills when the kids got out on recess and we had to stop! The kids would be getting in the huddles. We tried to shoo them away. A teacher came over and said the school belonged to the kids and not to us, and when it was recess time, it was the kids’ time. So we had to get off the field every time there was a recess.

The Patriots played their first game at Boston University Nickerson Field against the Denver Broncos on Sept. 9, 1960. The Patriots lost, and went 5-and-9 for the season.

The next year the team compiled a 9-and-4 record, selling out their first game on Nov. 3, 1961. On the last play of the game, the opposing quarterback threw what would have been a game-tying touchdown pass – only a fan walked onto the field and knocked the ball away. The call stood, and the Patriots knew they had a fan base.

Winning Streak

The next two years were good ones in New England Patriots history. The team went 9-and-4 in 1962 and the next year won the AFL East championship.

They had a defensive tackle named Larry Eisenhauer, nicknamed “Wild Man.” He psyched himself up before games by bashing lockers, walls or his teammates and once ran onto a football field in Kansas wearing nothing but his helmet and a jock strap. He sent five opposing quarterbacks to the bench for visits with the doctor.

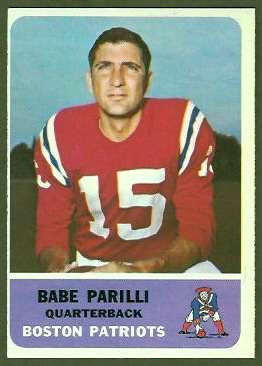

Quarterback Vito “Babe” Parilli played for the Patriots from 1961-67, passing for more than 20,000 yards. He was also an outstanding kick holder, nicknamed “Goldfinger.” The combination of Parilli and Cappelletti, who kicked and received, came to be known as the Grand Opera.

The Rush Years

The nutty, hapless Clive Rush took over in 1968, starting off badly. When he took the microphone to introduce the new general manager, George Sauer, he was stunned by a five-second electric shock. He thought the locker room was bugged, so he announced plays and blocking assignments in a loud voice while shaking his head, ‘No.’ When he announced he would implement a “Black Power Defense,” with all black players, he forgot the Patriots didn’t have 11 black players.

Rush once got off the team bus because he thought the driver didn’t know where he was going. He then directed the bus down a one-way street — the wrong way.

In 1970, he cut running back Bob Gladieux a few days before the season opener. Gladieux decided to attend the game anyway. Shortly before the game began, a loudspeaker announcement summoned him to the locker room. Rush had cut a defensive back five minutes before kickoff and needed Gladieux to fill the empty roster spot. Gladieux made the game’s first tackle and played eight more games for the Patriots.

Rush won five of 21 games and quit at the end of the 1970 season.

Home At Last

The Patriots’ perennial homelessness added to their early woes. They played at BU’s Nickerson Field, Boston College Alumni Stadium, Harvard Stadium and Fenway Park. They even played one game at Birmingham, Ala., Legion Field because of a scheduling conflict at Fenway.

The players sat on milk cartons in high school stadiums to watch game films projected onto bed sheets. Despite Sullivan’s best efforts, he could not persuade the Massachusetts Legislature to fund a new stadium.

In 1970, E.M. Loew, owner of movie theaters and Bay State Raceway in Foxborough, donated a parcel of land next to his racetrack if the Patriots would give him a cut of the parking profits. Ground was broken on Sept. 23, 1970. Eleven months and $7.1 million later, Schaefer Stadium was completed.

The first game was played a month before the regular season — between the carpenters and the metalworkers. The carpenters claimed the right to erect the goalposts, which were usually made of wood. These were made of aluminum, and the metalworkers claimed the right to raise them. Sullivan handed them a ball and told them to play a game of touch football. The first team to score would erect the goalposts.

Billy Sullivan decided to rename the team, and for two weeks the Patriots were the Bay State Patriots. Then someone pointed out the likely headlines: BS Patriots. He realized he had to come up with another name.

The rest is New England Patriots history.

With thanks to New England Patriots: The Complete Illustrated History by Christopher Price and The Most Memorable Games in Patriots History: The Oral History of a Legendary Team by Bernard M. Corbett and Jim Baker. This story about New England Patriots history was updated in 2022.

Image: Pat Patriot By The logo may be obtained through the New England Patriots, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18256803.