Under Puritan justice in 17th century New Haven, rumors of sex with a pig got you hanged, exposing sexual harassment got you whipped and disagreeing with a minister got you hauled into court.

Jon Blue, a Connecticut Superior Court judge, found these long-forgotten court cases of the New Haven Colony in a courthouse library.

“I was finding these old records that no one had looked at for years,” he said in an interview. “It was like Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

He deciphered the handwritten, archaic notes from the trials and wrote a book about them, called The Case of the Piglet’s Paternity: Trials from the New Haven Colony, 1639-1663. The case notes tell us much about day-to-day life in the New Haven Colony and present what Blue calls ‘a broad menu of disturbing cases.’

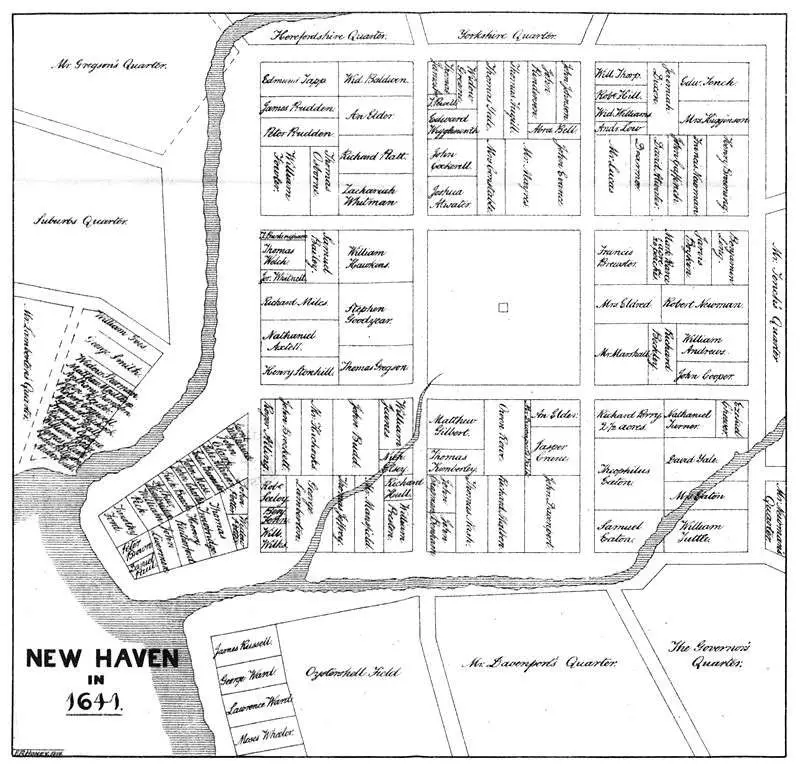

New Haven Colony

Puritans established New Haven Colony as a moral community – another theocratic ‘city on a hill’ — that adhered to Biblical law. The Puritans who ran New Haven saw their role as enforcing adherence to church doctrine.

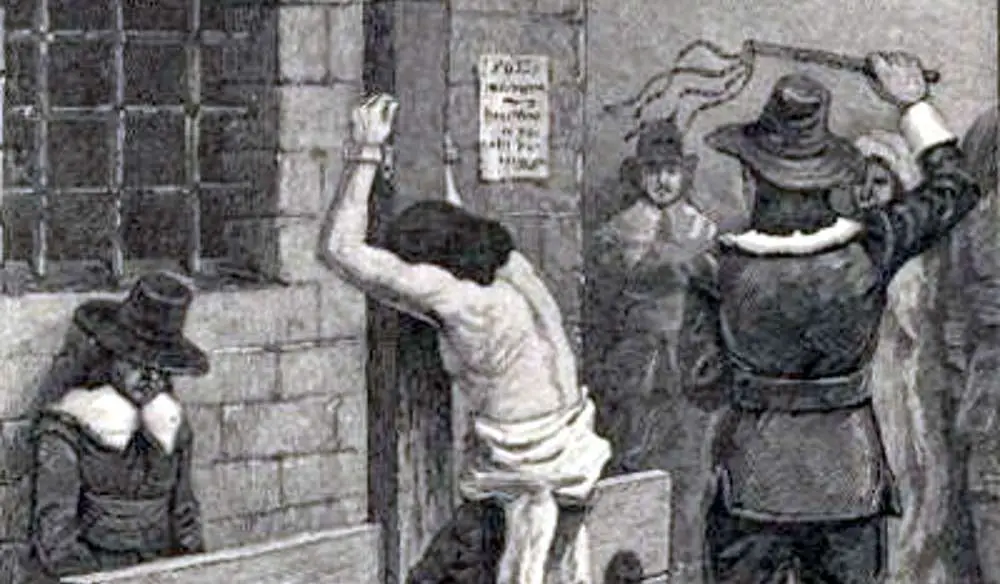

The court, at its Solomonic best, divided an estate between a widow and her children. At its worst, it ordered a small girl to be whipped and sold into slavery. Unlike Massachusetts, at least, the New Haven General Court refrained from such cruel punishments as ear-cropping, branding or boring holes in people’s tongues. But it did order whippings and hangings.

The court records reveal a society as scary and Orwellian, with spies everywhere. The smallest hint of religious dissent could land a person in court.

Blue compared early New Haven with North Korea.

Map of New Haven in 1638.

In the case of three dissident women, a servant overheard her mistress and two others disagree with their minister. She asked another servant to help her eavesdrop, then went to the authorities with what she’d heard. The three women went to trial on a dozen charges. One woman was even accused of criticizing authorities for ordering people to be cruelly whipped. The disposition of the case is lost to history.

Puritan Justice for Women

The New Haven Colony made no distinction between consensual and nonconsensual sex. It was also not a good place to be a poor, low-status woman, as the Goodwife Fancy case shows.

Goodwife Fancy belonged to the lowest of the low. She and her husband lived in the cellars of other people’s houses, moving around frequently. She did menial work in the fields and kitchens of wealthier women. At every turn, men groped and abused her. One day, for example, she found herself alone in a cellar with a Thomas Robinson.

He took hold of her, pulled down his breeches, put his hand under her skirt, and “with strength and force labored to satisfy his lust and to defile her.” When she cried out, he covered her mouth. He finally left when he heard some shipmen calling him.

This happened over and over, but Goodwife Fancy kept quiet, knowing what could happen to her. A third party went to the magistrate with the story of her sexual harassment. She had to testify under oath. The court believed her story – and ordered her and her husband whipped along with one of the men who had attacked her.

“Reading this travesty of a case, the modern reader cannot help but despair at the human condition,” concludes Blue in the book.

The Brickmaker’s Apprentice

Though Blue admired some of the New Haven court’s decisions, he found the way it treated children disturbing. Puritans viewed children as small adults, he said, and tried and punished them as such.

In ‘The Brickmaker’s Apprentice,’ a 13-year-old English boy named Edward House was sold as an indentured servant on the condition he be taught the brickmaker’s trade. He was sold and resold again, though he was infirm, and he was not taught to make bricks. In the end, the court ordered the boy be taught a trade.

The enduring image of the case is its pathetic inception, writes Blue.

Picture the young House, a boy of twelve or thirteen years, alone on a ship bound from England to the New World. This was not a young man adventurously off to see the world. This was a boy unaccompanied by his parents, apprenticed for seven years to a man in Boston whom he almost certainly did not know. His master was the ship’s cook, who ungenerously fed him a diet rivaling that of Oliver Twist. Instead of thin gruel, House had to subsist on bread soaked in fat. As a result, he developed scurvy.

Starving and malnourished, House had to drink liquor and then sign an even more onerous indenture. If he didn’t, he’d get thrown overboard. Arriving on land, his owners sold him again and again like a sack of wheat or, more accurately, a slave. He was bled, which undoubtedly made his medical condition worse. He had a sore that festered and he was so diseased that he was hardly fit for service.

The Pig’s Paternity

In New Haven in 1642, a sow gave birth to a piglet with one large eye and no hair on its entire body. The belief prevailed then that sex between species could produce offspring.

The weird animal went before the magistrates, who decided the piglet looked like a servant named George Spencer. Spencer worked on the farm where the piglet’s sow lived, and he had one deformed eye himself.

Spencer confessed to having sex with the sow, then recanted. He confessed again, and recanted again. Finally he went to trial, where he received a guilty verdict. Turning to Biblical law, Leviticus 20:15, the pig was to be killed in Spencer’s presence, and Spencer was to be hanged.

On April 8, 1642, the terrible sentence was carried out on both pig and man.

”These were people who shared the belief system of the time,” Blue said. “It should make us sober about our limitations today.”

This story last updated in 2021.