In 1879, Leroy Shear of St. Albans, Vt., an honest, mild-mannered and respected banker, traveled to Washington D.C., to meet with President Rutherford Hayes. Active in Republican politics, Shear’s name had been put forward for a federal post. There were just a few minor matters to clear up. Leroy Shear wasn’t honest. He wasn’t mild-mannered. And he wasn’t even really Leroy Shear.

Lorenzo, Not Leroy

Leroy Shear was born Lorenzo C. Stewart in 1838 in upstate New York. He enlisted to fight for the Union in the Civil War, and he served as a private in the 14th Regiment of the New York Artillery in 1863. By this point in his life, Shear had already married one wife and deserted her. Working in the ordnance department of the artillery unit, Stewart was highly regarded – so highly regarded another regiment offered him a chance for a promotion. One problem: Shear would have to desert the 14th to take the higher position.

In October of 1863 that’s exactly what he did – except he got caught. He was placed under arrest and imprisoned in Elmira, awaiting trial. But he was secretly scheming. On October 30, he feigned illness and convinced his guards to take him to two pharmacies in town. There he asked the druggists a lot of questions about morphine, which he bought.

The following evening, October 31st, he visited the guards in the cook-house and offered them some whiskey – which he had adulterated with the morphine. He had a simple plan. The guards would fall asleep under the influence of the drug, and he would escape. But his plan misfired. Several guards did pass out. Two died and the others got very sick. But Stewart didn’t get away. Instead, he was arrested – still in possession of some of the morphine. This time he was tried for murder and was ordered shot.

Was Leroy Shear Insane?

President Lincoln received a petition for clemency from Stewart’s friends who asked for leniency because of Stewart’s youth, the inducement to desert and because he didn’t intend to kill anyone. Further, they raised the issue of his sanity. Stewart had suffered a severe head injury in a fall at age five, which his mother believed changed his personality. At 15 he suffered what appeared to be sunstroke. He had a history of severe headaches accompanied by drowsiness, nosebleeds and bouts of delirium.

Lincoln ordered the execution stayed and asked John P. Gray, superintendent of the lunatic asylum in Utica, to assess Stewart’s competence. Gray’s report, following an investigation in April of 1864, was mixed. Stewart did suffer from delusions, after which he had no memory of his actions. But he was not insane, Gray concluded.

John P. Gray

Gray found Stewart to be erratic and peculiar with a short attention span. He had a history of writing absurd and false letters, often under false names. At the same time, Gray noted Stewart was intelligent, successful in business, an avid reader and a quick study. However, he found him lacking in character.

“From the earliest period of this development of his character, even before he was six years of age, he exhibited great moral defects. These have appeared principally in his disregard of the rights of property, and in his untruthfulness. He has always shown himself utterly unworthy of confidence, in every relation of life, and in every position in which he has been placed,” Gray wrote.

Moral Defects

Aside from instances where he pulled the hair of fellow inmates and threw water at them, Gray found little to support the notion that Stewart was insane. Rather, he concluded, Stewart was eccentric.

President Lincoln, after reviewing the matter, would commute Stewart’s sentence from death to 10 years at hard labor. By the time of the commutation, however, Stewart had managed to escape. This time, he disappeared for good. First he travelled to Europe and then back to Vermont. There he found a position at a bank and lived as a respected member of the community.

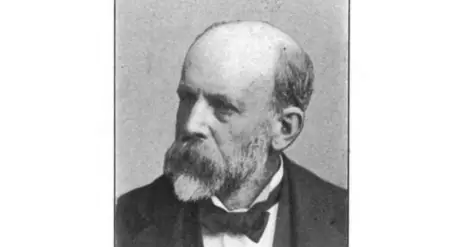

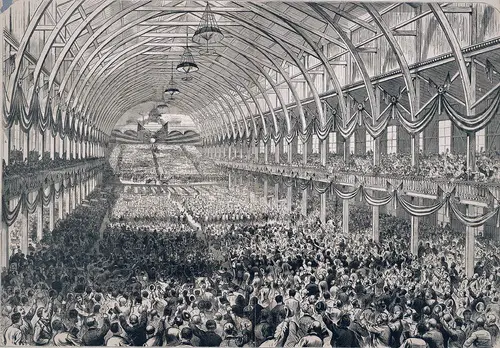

1876 Republican National Convention

By the 1870s, Stewart had become Leroy Channing Shear. He was a delegate to the Republican National Convention and his name was placed before President Rutherford Hayes for a federal position. For that reason he travelled to Washington to meet the president.

Far from receiving the presidential pardon he sought, Hayes learned about his past. He rescinded any offers of government service and sent him back to Vermont .

It wasn’t long before news of Shear’s past reached his hometown. The bank fired him and he had to leave. From there, Shear’s life took a definite downturn. He obtained a job at a building and loan company in Syracuse, but ran off with money he embezzled. In 1884, police arrested him in Burlington, Vt. The charge: he had written fraudulent checks in New York City.

Leroy Shear, Jailbird

Shear pleaded guilty and was sentenced to five years in prison. Over the next 25 years, Shear would spend as much or more time in prison than out. A master forger, he adopted Charles R. Clark, William M. Davis and Frank Mallory as his alter egos. His habit of fanciful exaggeration and signing false names, learned as a child, now became his stock in trade.

Shear would visit a city, buy some goods or pay a hotel bill with a check and request some additional funds. Typically Shear would write a $100 check to cover a bill for $40 or so, and depart with his purchases and extra cash. It would b weeks before his fraud was discovered.

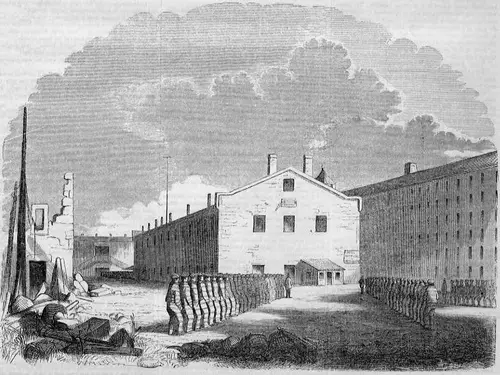

Sing Sing Prison

The American Bankers Association grew so frustrated with Shear that they hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to track him down. In 1902, the agency succeeded. After circulating his photograph around the country, one of their operatives spotted him and followed him to his residence. After one of his victims identified him, he ended up with a four-year sentence in Sing Sing prison in New York. There he worked as a teacher in the prison classrooms.

This story updated in 2023.

Images: 1876 Republican National Convention By Cornell University Library – originally posted to Flickr as Ohio – The Republican National Convention at Cincinnati, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=55633710.