Over the course of New England history many thousands of workers were killed on the job.

Some, like Vermont quarry workers, died a slow death from silicosis. Others like Connecticut munitions workers died suddenly in explosions.

Carelessness killed some. Nature killed others. Sometimes law enforcement officers killed workers because they challenged the bosses over working conditions and pay.

Here are six places in and around New England where workers were killed because of their jobs. If you know of other historic places where workers were killed, please add them in the comments section.

Remington Arms

The New York Times called the enormous Remington Arms plant in Bridgeport, Conn., ‘the greatest small arms and ammunition plant in the world.’ It may also have ranked as the deadliest.

At its height, Remington Arms employed more than 17,000 workers. Some of them died on the job. On April 4, 1905, three workers lost their lives in an explosion that blew up an entire building. In 1914, Bridgeport police killed an 18-year-old striking worker, Frank Monte.

On March 28, 1942, an explosion killed four women and three men and hurt 80 others. The blast shook the enormous munitions plant about 2 p.m. It “sent bullets whizzing dangerously through the vicinity, touched off a general fire alarm and brought a rush of ambulances,” reported the Boston Globe.

Investigators blamed the explosion on a nail that fell into a box of cartridge primers.

Today the abandoned Remington Arms plant still sits at 812 Barnum Ave. in Bridgeport. Since workers were killed there, it is said to be haunted.

The Penobscot River

Joe Attien, a Penobscot Indian chief, worked for seasonal wages as a logger and a Maine guide. Logging work carried many dangers and cost many workers their lives.

Joe Attien first appeared in print when Henry David Thoreau wrote about him in his 1864 book, The Maine Woods. Thoreau wrote, somewhat condescendingly:

He was a good looking Indian, twenty-four years old, apparently of unmixed blood, short and stout, with a broad face and reddish complexion, and eyes, methinks, narrower and more turned up at the outer corners than ours.

On July 4, 1870, Joe Attien led a team of log drivers down the Penobscot River in a bateau. River drives usually ended by Independence Day, when the men went into Bangor and celebrated with a vengeance.

In 1870, though, rough water delayed the West Branch drive. On July 4, the rivermen tried to break up a logjam. They launched a bateau with seven men, captained by Joe Attien from the stern.

The churning water shot the boat across the channel and smashed it against the rocks. The collision sheared off a hole in the bateau, which quickly filled with water. The unmanageable craft hurtled over a waterfall among the rocks and logs. Some of the men couldn’t swim, and Joe Attien died trying to save them.

When the river drivers found his body, they cut a cross into a tree by the side of the pond, and hung his boots in the tree. The boots then stayed there until they rotted away, a sincere memorial of a good man.

Today you can learn more about Maine’s logging history by visiting the Maine Forestry Museum in Rangeley, Maine.

Georges Banks

Fishing has long ranked as one of the deadliest occupations in the United States. In 1841, so many Cape Cod fishermen perished in an October storm that the peninsula’s young women wouldn’t court men who went to sea.

On Saturday, Oct. 2, 1841, most of the Truro fishing fleet on the Georges Banks left off fishing and made for home. Only two of the nine ships that set out made it.

The wind kicked up that afternoon and reached gale force by midnight. “The ocean roared as though with an unbridled madness,” wrote Sidney Perley in Historic Storms of New England. “Its waves ran mountain high, throwing their spray far into the sky, and forming a majestic yet fearful sight.”

Cape Cod suffered the most from the storm. Parts of 50 shipwrecks washed onto the beach from Chatham to the highlands. In one day, searchers took up 100 bodies and buried them. The Truro Insurance Company failed for a lack of men to take charge of its vessels.

In the seven fishing vessels out of Truro, 57 men and boys died at sea, and only a few of their bodies were recovered. All 57 lived within two miles of each other. They had relatives throughout the town. Eight Snows and eight Paines died. So did three boys not yet 13 years old.

An obelisk in Truro’s First Congregational Parish Church yard commemorates the 57 storm victims at 26 Bridge St. in Truro.

Amoskeag Mills

Ida Cram and Mary Kane worked at the Amoskeag Mills in Manchester, N.H., on the morning of October 15, 1891. On that day all hell broke loose at the facility’s Number 7 mill.

The Amoskeag, the largest cotton textile plant in the world, had installed a mammoth Corliss steam engine to deliver power to four of its plants. But steam engines in the 1800s were risky machines. They powered the industrial revolution, but maintaining and operating required a new skill that many had not mastered.

That morning in 1891, Amoskeag management had concerns about the steam engine, which seemed erratic. An engineer, Samuel Bunker, was dispatched to the engine room to see if he could find the source of the problem. No one knows if Bunker ever found exactly what went wrong because debris from the giant Corliss engine killed him when its flywheel flew apart.

Ida Cram and Mary Kane also dieed in the explosion, which showered the mills with debris and sent raging blasts of steam from the broken machinery. Dozens were injured. Investigators never conclusively figured out the reason for the blast that sent three people to the grave.

Today, visitors can tour parts of the historic Amoskeag mills that are home to the Manchester Millyard Museum.

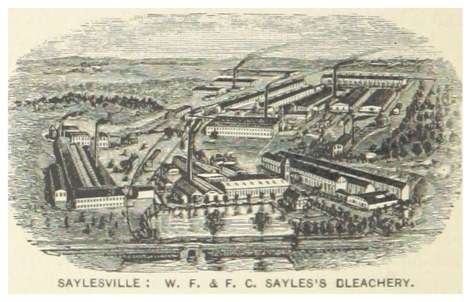

Sayles Finishing Plants

William Sayles started a bleachery in Lincoln, R.I., which grew into the enormous Sayles Finishing Plants in the 1920s. By then, mill owners tried to squeeze more and more work out of their employees because demand for textiles had slackened while competition stiffened from foreign mills.

In the fall of 1934, unions organized a general strike throughout the textile industry – the largest in U.S. labor history. From New England to the South, 400,000 textile workers walked off the job. The strike lasted 22 days.

Strikers stopped work at Sayles, but the company hired strikebreakers to continue production. Several thousand strikers shut down the factory. Rhode Island Gov. T.F. Green ordered state troopers and deputy sheriffs to police the strikers. They arrived wielding machine guns and tear gas bombs against the unarmed workers. They fired on strikers hiding in the Moshassuck Cemetery, killing Charles Gorczynski, a 17-year-old textile worker from Central Falls. Workers carried his body through Pawtucket in an enormous funeral procession.

Police later shot and killed William Blackwood, a 44-year-old onlooker. In the end, eight strike sympathizers and four striking workers were killed, and 132 people were injured in what became known as the Saylesville Massacre.

Today, you can visit the Moshassuck Cemetery at 978 Lonsdale Ave. in Central Falls. You can also see the Sayles’ mills and workers housing in the Saylesville Historic District in Lincoln, R.I.

Proctor Marble Factory

On May 22, 1903, Janos Szlaby, a Hungarian immigrant, worked the graveyard shift at the Vermont Marble Company at Proctor, Vt.

A belt that turned the stone-finishing machinery in one of the plants snagged. The supervisor sent Szlaby to free the belt with the factory machinery whirring below. Szlaby slipped and tumbled into the factory’s balance wheel, which crushed him to death.

Countless other workers were killed in Vermont’s quarrying and stone-finishing industries.

More pernicious than the sudden deaths in the quarries and plants, however, were the lung ailments that stone workers suffered from years of exposure to stone dust. Pneumatic tools that replaced hand tools threw off great clouds of dust in enclosed work spaces. Workers worried about their lungs confronted company managers who wanted the more efficient modern equipment.

In 1909 a group of stonecutters walked off the job in Northfield, Vt. They did it because the company bought handheld surfacing tools that threw off too much dust. In the early 1900s labor agreements included language about tamping down dust on the job. But the methods didn’t work. One study of how stonecutting workers were killed in the 1920s and 1930s found silicosis cost them 11 years of their lives.

You can visit one of Vermont’s marble quarries at the Proctor Marble Museum.

Images: First Congregational Parish of Truro By Judy Moehle – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35518602. This story about where workers were killed was updated in 2023.