When French-Canadians came to work in New England’s textile mills in the later 19th century they sparked conspiracy theories of an immigrant conquest. Even the New York Times claimed that there were secret attempts to turn New England into New France.

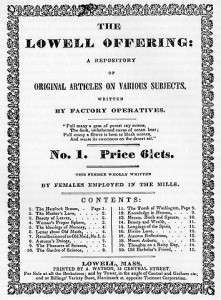

Lowell Mill Girls

In its earliest years, women were the main component of New England’s textile workforce. In the 1840s, an increasing number of European immigrants came to operate the textile machinery. Then came the Civil War, a disaster for cotton textiles, New England’s largest 19th century industry. New England’s mills were devastated by the Union blockade of Confederate ports during the war that hindered southern cotton from reaching northern shores.

Some New England mills closed their doors, while others slashed their hours. A contemporary observer described the result in the flagship mill town of Lowell, Mass.: nine corporations shut down and 10,000 workers thrown “penniless, into the streets.”

After the war, New England’s textile manufacturers found that their workforce had scattered and was not returning to the mills. To save the industry – and New England’s economy – the textile corporations scoured the rural areas of the region. They also searched Europe and Canada for laborers. Canada’s French-speaking province of Quebec responded to this call en masse.

Newcomers

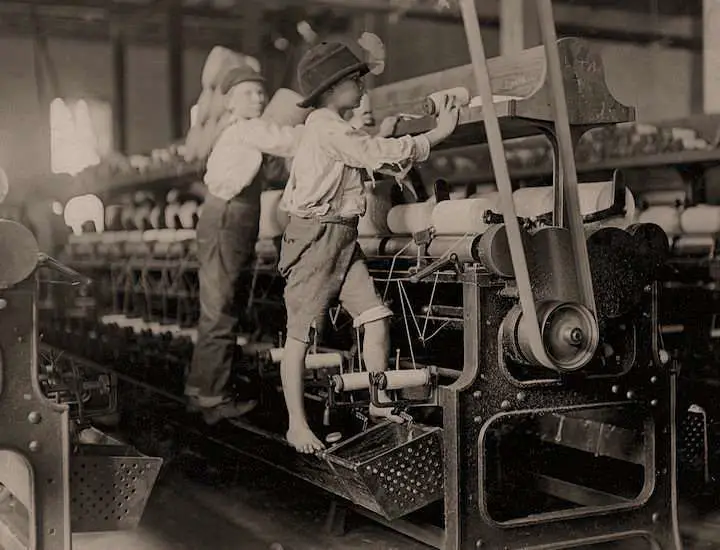

In the years between 1865 and 1900, hundreds of thousands of French-Canadians crossed the border in search of work in New England’s factories. By the beginning of the 20th century, French-Canadian men, women and children comprised 44 percent of the region’s cotton textile workforce.

Young millworkers from Manchester’s Little Canada, 1909. Photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, courtesy Library of Congress.

During this period French-Canadians established Little Canadas in industrial towns from Lake Champlain to the Blackstone River Valley, and from the coasts of Maine to the Connecticut River. In towns such as Woonsocket, R.I., and Biddeford, Maine, the French-Canadians eventually became the majority, electing their own as mayors.

St. Ann’s Church complex, Woonsocket. It was built with nickels and dimes from French-Canadian millworkers.

Throughout the region, the newcomers from the North preserved their French language, their Catholic religion and the traditions of their rural Canadian parishes. They established their own schools, and a host of mutual benefit and social organizations. They intended to preserve their French-Canadian identity within the U.S.

A Conspiracy Theory About an Immigrant Conquest

The French-Canadian desire to maintain their language and customs raised alarm bells in New England and throughout the U.S. So did their heavy concentration in densely populated neighborhoods and their ever-increasing numbers. The mainstream press reported on an alleged invasion of New England by immigrants from across the border. Major media outlets including the New York Times, Harper’s and The Nation weighed-in on the political, economic and social implications of this cross-border influx.

In the period between 1880 and 1900, elements in the press spun a conspiracy theory around the French-Canadian newcomers. Some commentators theorized that the Catholic Church had dispatched the French-Canadian workers into New England in a bid to take over the region on behalf of the church. The French-Canadian workers, claimed these conspiracists, would first seize political control of the region. Then, went the theory, Quebec would declare its independence and annex New England to create a revived New France.

Increasing Alarmism

The New York Times repeated these claims on several occasions throughout the 1880s and 1890s. In 1885, the paper stated that there were plans afoot “to form a new France occupying the whole northeast corner of the continent.” Returning to the story in 1889, the Times stated that this supposed revival of New France would include, “Quebec, Ontario, as far west as Hamilton, such portions of the maritime provinces as may be deemed worth taking, the New-England States, and a slice of New-York.”

Notre Dame of Montreal Basilica

The newspaper’s rhetoric became increasingly alarmist over time. By 1892, the Times opined that French-Canadian immigration was “part of a priestly scheme now fervently fostered in Canada for the purpose of bringing New-England under the control of the Roman Catholic faith…This is the avowed purpose of the secret society to which every adult French Canadian belongs.”

This editorial seems to have imputed subversive intent to the French-Canadians’ mutual aid societies. In fact, these groups offered insurance and other benefits unavailable to French-Canadian Catholics elsewhere. Such groups were not oriented around the conquest of New England. It was simply false to assert that “every adult French Canadian” belonged to them.

Protestant Efforts To Convert French-Canadians

Some Protestant clergy climbed on the immigrant conquest conspiracy bandwagon. They responded with initiatives to convert the French-Canadians. The Congregationalists of Massachusetts supported Rev. Calvin Elijah Amaron, a missionary who established the French Protestant College at Lowell. A few years later, he moved it to Springfield, Mass. A major aim of this college, today known as the American International College, was to train French-speaking Protestant missionaries to go forth and convert the French-Canadians of New England and Quebec.

American International College in Springfield, Mass.

In 1891, Amaron published a book called Your Heritage; or, New England Threatened. It was a long-form treatment of the theory that a French-Canadian Catholic cabal planned to undermine New England. In Amaron’s mind, Roman Catholics could not be reliable U.S. citizens since they owed their first allegiance to Rome. The “Romish clergy,” Amaron wrote, forced its adherents into a “moral and intellectual bondage” that is “worse than southern slavery.”

The Gospel Wagon

The Baptists also made efforts to convert the French-Canadians of New England. Statistics cited in the 1906 book Aliens or Americans? by Howard Grose showed that the Baptists expended more resources on missionary activities to convert the French-Canadians than on any other predominantly Catholic group in the United States.

The Baptists’ Henry Lyman Morehouse, in an 1893 article titled The French Canadian in Quebec and New England, compared the effort to convert the French-Canadians to the abolitionist movement. “Slavery in the United States has gone,” Morehouse wrote. “The next great act of emancipation is that which shall free from mental and religious servitude the people of Quebec…”

Henry Lyman Morehouse

The Baptists also fielded a contraption called the Gospel Wagon. A large horse-drawn vehicle, it had a pulpit, organ and lanterns for preaching by night. Missionaries deployed the wagon in Massachusetts and New Hampshire mill towns, preaching Protestantism to the French-Canadian enclaves from their customized vehicle.

Immigrant Conquest Conspiracy Countered

Other voices countered the rhetoric about an immigrant conquest conspiracy. William MacDonald, a professor at Bowdoin College, disputed the notion that the Canadiens were a threat to the region. In an 1896 article in The Nation, MacDonald soberly recounted the facts showing that a French-Canadian demographic takeover of New England was unlikely. MacDonald also summarized the region’s attitude toward the French-Canadians in their midst:

Useful and indispensable as they have become, they are nowhere received with cordiality, or commonly referred to save as an inferior class; even their religion is denounced as un-American, and the influence of the Church little regarded or else misconstrued….As a class, they are treated considerately in public because of their votes, disparaged in private because of general dislike and sought by all for the work they do and the money they spend.

The conspiracy theorists offered little evidence to buttress their claims beyond a handful of utterances from the ultra-Catholic wing of the French-Canadian elites in Quebec. A few firebrands in Quebec had made expansionist noises. But, then as now, the political future of Quebec was hotly debated. There were many views on the subject. There was no semblance of unanimity in Quebec around the notion of a revived New France that would include New England.

Most of the workers coming from French Canada to New England were poor farmers, their non-inheriting adult children, day-laborers and wage earners in small Canadian factories. Their motives for crossing the border were chiefly economic rather than political or religious. Jobs and steady wages were the magnets attracting them southward.

French-Canadians Assert Their Patriotism

While conspiracy theorists were proclaiming that the newcomers were incapable of U.S. citizenship, New England’s small French-Canadian elite were voicing their American patriotism at a series of national conventions held throughout the U.S.

French-Canadian family arriving from Montreal.

At these French-Canadian conventions, speakers pointed to their people’s service in the U.S. military dating to the American Revolution. They also highlighted their historical role in settling the U.S. Midwest. They or their French cousins had founded or helped to found Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Louis, as well as Natchez, Mobile, New Orleans and numerous other cities.

Convention delegates also encouraged their people to become naturalized U.S. citizens. Contrary to the theory that Quebec planned to annex New England, many French-Canadians in the States favored U.S. annexation of Canada.

The End of a Conspiracy

The fear of a French-Canadian conspiracy subsided in the early 20th century as newcomers from Southern and Eastern Europe began to enter the U.S. in increasing numbers. New England manufacturing slowly lost its lead in the textile industry to the U.S. South beginning in the 1920s.

As the mills faded away, the Little Canadas gradually dispersed, a process that continued throughout the 20th century. And along with these enclaves went the memory of a period when some Americans considered poor French-Canadian mill workers a threat to New England’s way of life.

David Vermette is the author of this story about fears of an immigrant conquest, updated in 2023. He is a writer, researcher and editor born and raised in Massachusetts. He wrote the book A Distinct Alien Race: The Untold Story of Franco-Americans (Montreal: Baraka Books, 2018).