Even before European colonists thinned the Indian population in New England, war and disease had already begun their dirty work.

A team of anthropologists, economists and paleopathologists studied the health of the Indian population in the Western Hemisphere over 7,000 years. Native American health had declined even before Columbus came to the New World, they concluded in a book published in August 2017, The Backbone of History: Health and Nutrition in the Western Hemisphere.

The researchers found Indians’ health got worse because they came to depend on corn. They also began to live in denser communities, allowing infectious disease to spread quickly.

Still, the Indian population didn’t begin its demise until the Europeans arrived in the 16th century.

About 60,000 Indians lived in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut at the beginning of the 17th century, according to Sherburne Cook. Maine had a robust population of Abenaki tribes. According to some estimates, Maine had more than 20,000 Penobscot, Micmac and Passamaquoddy Indians.

A century later, New England’s Indian population began to disappear. Some tribes were already extinct.

This is how the Europeans nearly wiped out the Indian population.

Indian Population Before the Pilgrims

The seeds of the Indians’ destruction were planted more than a century before the Pilgrims set foot on Plymouth Rock.

In what is now Canada and Maine, contact with Europeans began even before English and French explorers showed up at the turn of the 16th century. In 1504, a French vessel was documented fishing the Grand Banks off Newfoundland. Portuguese fishermen arrived two years later.

By 1519, a hundred European ships made round trips to the Grand Banks. The first tourist cruise to North America sailed from London in 1536, but food ran short and many died.

The European visitors brought with them diseases to which the Indians had no immunity, including smallpox, measles, tuberculosis, cholera and bubonic plague.

Maine’s Passamaquoddy Indians, among the first to make contact with Europeans, were devastated by a typhus epidemic in 1586. Other diseases brought the Passamaquoddy population to 4,000 from 20,000.

The 1616 Plague

In 1616, a terrible plague swept the Massachusetts coast, wreaking the most devastation north of Boston. It’s not clear what it was – perhaps smallpox, perhaps yellow fever, perhaps bubonic plague.

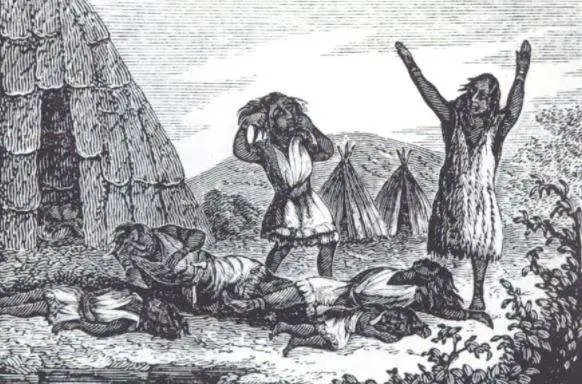

Whatever it was, it was terrifying. So much of the Indian population died there weren’t enough left to bury the dead. English colonist Thomas Morton described the heaps of dead Indians ‘a new found Golgotha.’

As many as 90 percent of the 4,500 Indians of the Massachusetts tribe perished. The disease cleared the Boston Harbor islands of inhabitants.

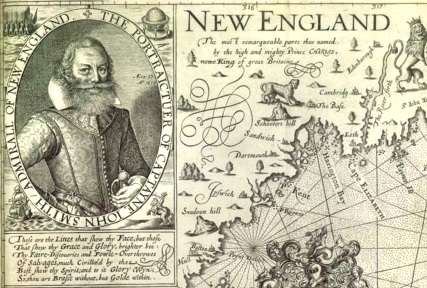

English explorer John Smith had visited New England before the plague in 1614. He returned eight years later, and what he saw shocked him.

“God had laid this country open for us,” he wrote. “Where I had seen 100 or 200 people, there is scarce ten to be found.”

Disease persisted among the Massachusetts from 1620 to 1630. When smallpox struck in 1633, it left only about 750 and obliterated entire villages. The colonists herded the Massachusetts who survived into Christian villages of ‘praying Indians.’

Puritan minister Increase Mather wrote ‘about this time [1631] the Indians began to be quarrelsome touching the Bounds of the Land which they had sold to the English, but God ended the Controversy by sending the Smallpox amongst the Indians of Saugust, who were before that time exceeding numerous.’

Along the Merrimack River in New Hampshire, Mohawk raids had already weakened the Pennacook Indians when the 1616 plague arrived. It killed three out of four Pennacooks.

That same plague almost completely obliterated two other Pennacook tribes in Massachusetts, the Agawam in Ipswich and the Naumkeag in Salem.

Wampanoags

The plague of 1616-1618 cleared nearly all the Wampanoag along the coast from Plymouth to Boston, but was far less severe south of Plymouth.

A year after the Pilgrims arrived, their Indian visitor Samoset told them, ‘about foure yeares agoe, all the Inhabitants dyed of an extraordinary plague, and there is neither man, woman, nor childe remaining, as indeed we haue found none, so as there is none to hinder our possession, or to lay claime unto it.’

“Thousands of them died,” wrote William Bradford, Plymouth’s governor. “They not being able to bury one another, their skulls and bones were found in many places lying still above the ground.”

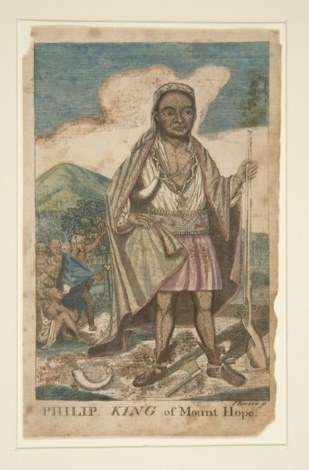

Enough Wampanoag Indians survived to resist the colonists’ land grab during King Philip’s War in 1675.

But disease persisted among the tribe, weakening it further. By the war’s outbreak, the Wampanoag Indian population fell to 2,500 from as many as 5,500. Those who weren’t killed in the war were sold into slavery, moved to praying towns or migrated west. King Philip’s War virtually obliterated the Wampanoag.

Narragansett

The Narragansett were the biggest tribe in New England, with 7,800 members including 300 on Block Island. Protected by Narragansett Bay, they didn’t come into contact with the white invaders as early or as frequently as northern tribes. The great plague of 1616 didn’t affect them.

Because the Narragansetts were so much larger, Wampanoag leader Massasoit made peace with the Plymouth colonists to ally them against his Narragansett rivals.

The Narragansetts’ first epidemic was smallpox in 1633, which killed 700 of them. Chronic ailments further reduced their numbers to 5,000 by the outbreak of King Philip’s War. Wrote Roger Williams in 1643,

They commonly abound with children, and increase mightily; except the plague fall amongst them, or other lesser sicknesses, and then having no means of recovery, they perish wonderfully.

Infectious disease terrified the Narragansetts. “I have often seene a poore House left alone in the wild Woods, all being fled, the living not being able to bury the dead, so terrible is the apprehension of an infectious disease, that not only persons, but Houses and the whole Towne take flight,” wrote Williams.

The Narragansetts tried to stay out of King Philip’s War, but after English colonists massacred as many as 1,100 of them at the Great Swamp Fight in 1675, they had no choice but to fight. After King Philip’s War fewer than 500 Narragansetts remained. They were allowed to settle with the Eastern Niantic on a reservation at Charlestown, R.I., where they frequently intermarried with African-Americans and Indians from other tribes.

The Nauset

The Nauset, a tribe of about 8,000 on Cape Cod and the islands, were also apparently unaffected by the plague of 1616. But other diseases gradually reduced their numbers. The 2,100 Nausets on Cape Cod were down to 1,250 by 1700, and all had been converted to Christianity. By 1660, they had been driven into the Mashpee Reservation; the population of 2,100 Nausets fell to 1,250 by 1700.

Disease had also reduced the Indian population of 6,000 on Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket by more than half, to 2,330.

Connecticut’s Indian Population

Before the English arrived, an Algonkian tribe that became the Pequots moved into Connecticut from the Connecticut River to the Rhode Island border, displacing the people who lived there. There were about 3,000 of them, and the population remained stable with little European contact and in the absence of war and severe epidemic disease.

Then English colonists and Mohegan warriors attacked them in the Pequot War of 1637. Hundreds were killed or captured and hundreds more fled to southwestern Connecticut and Long Island. Only 200 were left by war’s end, and they were absorbed into the Mohegan tribe.

Shortly after the Pequot War in 1643, there were about 2,200 Pequot-Mohegans. Smallpox, flu, diphtheria and measles reduced their numbers to 750 by 1705. By then, the colonists had already herded them into Connecticut reservations at Ledyard and Groton.

One Connecticut tribe tried to protect itself by building a fort. A thousand Mattabesic Indians sealed their fate when they enclosed themselves in a palisade fort in Hartford County. By 1634, smallpox and plague killed all but 50 of them with terrifying swiftness.

Of the 3,000 other Connecticut Indians in the vicinity – Podunk, Mattabesic, Hammonasset and Wongunk – most who survived sold their land and moved away.

Reservations

During the 17th century, life was short for the English colonists as well as the Indian population. By 1700, life expectancy in New England rose to 45-50 years, 15 years higher than in old England.

The Europeans had large families, and the colonist population grew 3 percent a year, doubling every 23 years. The land-hungry colonists pushed the remaining Indian population into warfare, and then into reservations and to parts west.

Before the Europeans arrived, about 10,000 Penobscot Indians lived in what is now Maine. The population collapsed from infectious diseases and fighting between the Iroquois over the fur trade. The Penobscot sided with the French during four Anglo-French wars, which the French ultimately lost.

The Indian Population Makes a Comeback

Both the Penobscot and the Passamaquoddy ceded their land to Massachusetts (which later became Maine). They had only a reservation on Indian Island in Old Town, Maine. By 1800, the Penobscot Indian population fell to 500.

Many Indians converted to Christianity and moved to one of 14 praying towns. Indians moved to reservations in Gay Head on Martha’s Vineyard and Fall River in Massachusetts.

During the 20th century, New England’s Indian population made a comeback. But that is a story for another day.

With thanks to The Indian Population of New England in the Seventeenth Century by S.F. Cook and to The Backbone of History: Health and Nutrition in the Western Hemisphere, edited by Richard H. Steckel, Jerome C. Rose. This story about New England’s Indian population was updated in 2022.