The Marlborough Pie once graced many a New England table during the winter holidays. It ranked up there with the pumpkin, the cranberry and the mincemeat, until it somehow fell out of favor in the late 19th century.

The Marlborough Pie resembles the pumpkin pie in texture, and some liken it to an apple-lemon custard in a crust. People sometimes ate the custard, in fact, without the crust. In that case, they called it Marlborough Pudding.

Marlborough Pie

One reason for its popularity at Thanksgiving, Christmas (for non-Puritans) and New Year was that it used apples harvested in the fall and about to go bad. Early New Englanders stored their apples in sand in a root cellar. Just before the holidays, the ones closest to rot and full of worms could be strained through a horsehair sieve and pureed.

Another reason people loved the Marlborough Pie: It uses a fair amount of booze.

Or maybe just because it tastes so good.

Marlborough Pie History

The Marlborough Pie is very old, dating to the 1600s, and very English, using apples, cream and butter. It also uses ingredients widely available in Tudor England: nutmeg from the Spice Islands, lemon from the Mediterranean and sherry from Spain.

St. Peter’s in Marlborough

No one really knows how it got the name Marlborough. Perhaps it came from the market town of Marlborough, 75 miles west of London, or the village of Marlborough in Devon. Or maybe a monk (Thomas of Marlborough) or a duke (Gen. John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough). It was definitely not named after Marlborough Street in Boston, which didn’t exist in the 17th century.

John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough

The pie, like so many New England foods, came with the early colonists from England.

Versions of the Marlborough pie appear in 18th-century English cookbooks, which also sold in the American colonies. It then appeared in the first American cookbook, Amelia Simmons’ American Cookery, published in Hartford in 1796.

TAKE 12 SPOONS OF STEWED APPLES, 12 OF WINE, 12 OF SUGAR, 12 OF MELTED BUTTER AND 12 OF BEATEN EGGS, A LITTLE CREAM, SPICE TO YOUR TASTE; LAY IN PASTE NO. 3, IN A DEEP DISH; BAKE ONE HOUR AND A QUARTER.

Some people called it a Deerfield Pie, though American food writer Clementine Paddleford called it a “Deerfield Marlborough Pie.” The Deerfield Pie uses more apples, leaves out the nutmeg and adds a teaspoon of grated lemon peel.

Pie Lovers

Pie historian Robert Cox told the New England Historical Society that pie culture is quite deep in New England. Think Boston Cream Pie, rhubarb pie, maple pie (beloved in Vermont), mincemeat pie, cranberry pie and pumpkin pie. Not to mention tourtiere, the meat pie that came from Canada, and seafood pies especially popular along the southern coast of New England.

Paddlwford wrote that if you told her where your grandmother came from and she could tell you how many pies you serve for Thanksgiving. Paddleford wrote.

An assembly of New England pies. Courtesy Library of Congress.

She noted that grandmothers Down East served a threesome – a sliver each of cranberry, mincemeat and pumpkin pie.

And sometimes, she wrote, “harking back to the old days around Boston, four kinds of pie were traditional for this feast occasion–mince, cranberry, pumpkin, and a kind called Marlborough, a glorification of the everyday apple.“

Marlborough Pie Memories

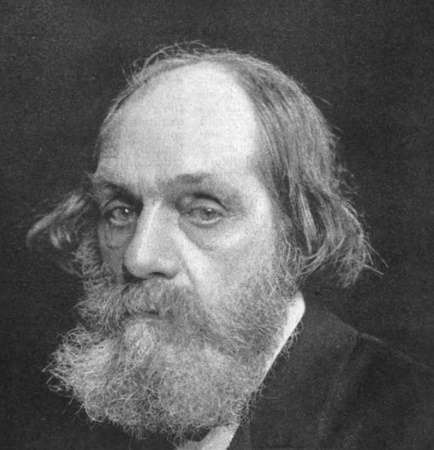

Author Edward Everett Hale, who wrote The Man Without a Country, spent his boyhood before the Civil War in Boston. Born in 1822, he recalled his early years in an autobiography published in 1900.

Edward Everett Hale

“There were certain peculiarities in the Thanksgiving dinner which there were not on common days,” he wrote. “For instance, there was always a great deal of talk about the Marlborough pies or the Marlborough pudding.

“To this hour, in any old and well-regulated family in New England, you will find there is a traditional method of making the Marlborough pie,” he wrote. And according to Hale, every good housekeeper thought her grandmother left a better recipe for it than anybody else did.

Fashion?

Did food fashion kill off the Marlborough Pie, the way it killed Election Cake?

By the 1840s, America was loosening its cultural ties to England and embracing language, entertainment and food uniquely American.

As an anonymous writer remarked in 1840 in a New York magazine, The Knickerbocker, “Persons of a certain age were very much under the domination of that absurd style which was emphatically called ‘GOOD OLD ENGLISH COOKERY’.”

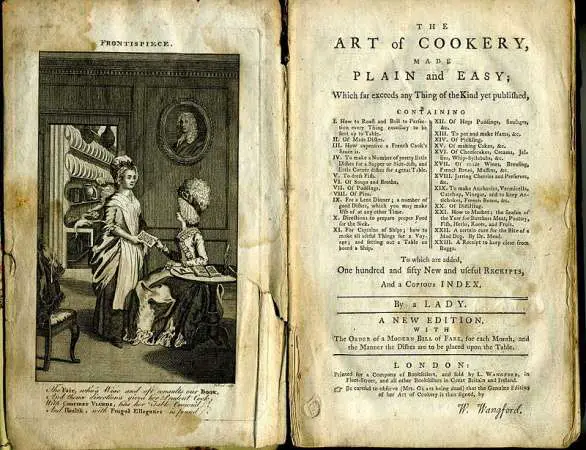

And then the writer took aim at London cookbook writer Hannah Glasse, who wrote the bestselling The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, in 1747.

“We had emancipated ourselves from the scepter of King George, but that of Hannah Glasse was extended without challenge over our fire-sides and dinner tables, with a sway far more imperative and absolute,” he (or she) wrote.

In 1896, Fannie Merritt Farmer published her first Boston Cooking School Cook-Book. It had not a whisper of the Marlborough Pie in it.

Temperance?

Did the temperance movement kill the Marlborough Pie? After all, the pie contains more than a little bit of sherry, or wine.

Temperance advocates, who started to gain strength in the mid-19th century, had an impact on cooking style. Women stopped poaching pears in port, turning to beet juice. Perhaps the Marlborough Pie custard without sherry just lacked that special something.

The Drunkard’s Progress by Nathaniel Currier, 1846

The food reform movement of the late 1800s may have also helped kill the Marlborough Pie. Food reformers – many of whom belonged to the temperance movement — advocated that people avoid refined foods, like sugar and flour.

Old Sturbridge

Food writer John T. Edge visited Old Sturbridge Village to research Apple Pie, his book published in 2004. Some of the foods Edward Everett Hale would have eaten as a boy – including Marlborough Pie — appear on tables in Old Sturbridge, which recreates life in the 1830s.

An Old Sturbridge Village kitchen and staff.

Today, the staff at Sturbridge Village still makes (and eats) Marlborough Pie. Here’s a truncated version of their recipe from Atlas Obscura.

Marlborough Pie

1 pie crust

6 tablespoons butter

3/4 cup apples peeled and cored (about 3 large or 4 small)

Juice from 1 lemon

3/4 cup sherry (the sweeter the better)

1/2 cup heavy cream

3/4 cup white sugar

4 eggs

Grated nutmeg to taste

Melt butter and set aside to cool. Cook the apples in a small amount of water until tender, then puree. Add lemon juice, sherry, cream and sugar to the apples. Add the butter. Beat the eggs and add to the mixture. Add nutmeg. Fold into a piecrust and bake about 1 hour in a 350 degree oven.

* * *

The Christmas holiday actually began in ancient Rome — and so did Italian cookies. The New England Historical Society’s new book, 24 Historic Italian Christmas Cookie Recipes, tells you how to make those delicious treats. It also bring you the history of the Italian immigrants who brought them to New England. Available now on Amazon; just click here.

Images: Marlborough, England: By This photo taken by Przemysław JahrAutorem zdjęcia jest Przemysław JahrWykorzystując zdjęcie proszę podać jako autora:Przemysław Jahr / Wikimedia Commons – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4308958. John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough By Adriaen van der Werff – Unknown source, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18505. Sturbridge Village By Alphanum3r1c at English Wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by Reaper Eternal., CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12722257.

With thanks to Apple Pie: An American Story by John T. Edge.

This story last updated in 2023.