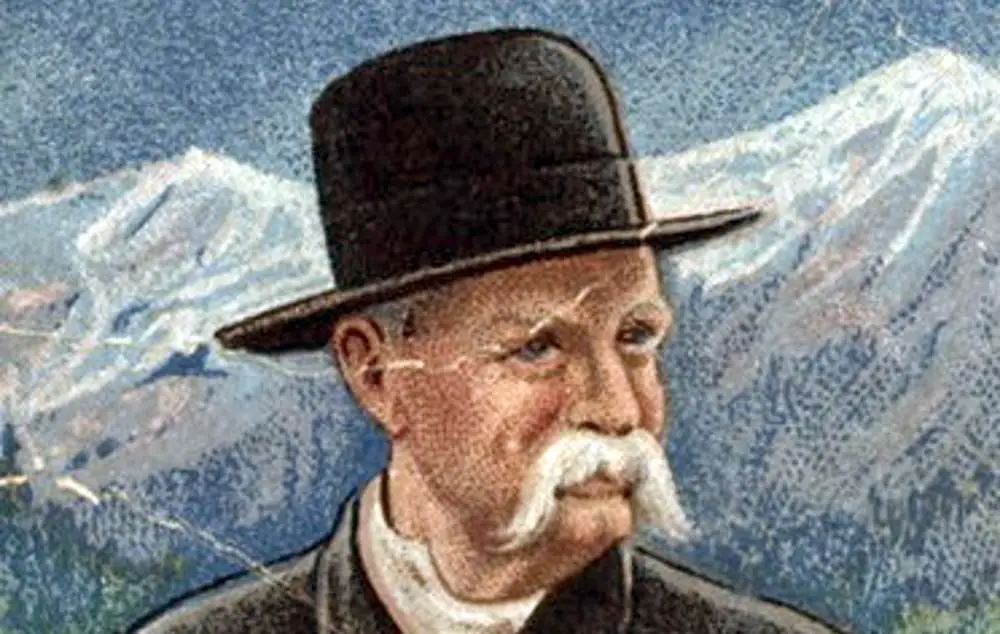

Edward Payson Weston became one of the most well-known celebrities of the Victorian Age by … walking.

He was born on March 15, 1839 in Providence, R.I., to a family of modest means. As a young man he struggled to find a career. In 1860, he bet a friend that Abraham Lincoln would lose the race for president. The loser had to walk the 478 miles from the Massachusetts Statehouse to the Capitol for Lincoln’s inauguration in 10 days.

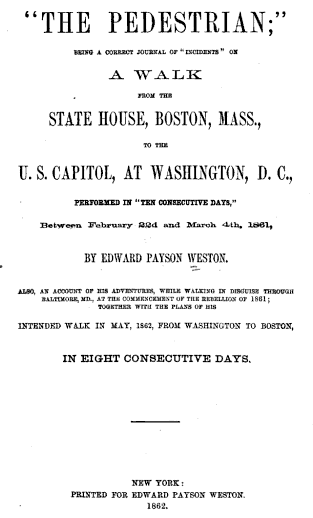

Weston lost the bet but found a profession. He was a show-off and a salesman, and he publicized the trip in advance and capitalized on it afterward. He wrote a melodramatic pamphlet chronicling the tragedies and triumphs of his walk from Boston to Washington, which launched his career as a professional pedestrian. Weston also sparked a craze for long-distance walking, or pedestrianism, which hit its peak in the late 1870s.

Before setting out for the nation’s capitol, he took a practice walk from New Haven to Hartford and back in less than 24 hours. The New York Times picked up the story. From then on, his perambulations would generate plenty of news.

Rubber Suit

He found sponsors to underwrite the walk, which required horses and a carriage for luggage, food and lodging. One of his sponsors, the Rubber Clothing Co., also gave him a rubber suit that kept him dry in the rain and snow.

A schedule was printed in advance and distributed along his route, which generated crowds of well-wishers. On Feb. 22, 1860, enthusiastic supporters greeted him at the Massachusetts Statehouse as he stepped out of his carriage. So did a constable, who arrested him for unpaid debts. Weston talked his way out of detention, promising to repay the debt.

He finally left to the cheers of the crowd, accompanied by a small entourage of friends in the carriage. That evening in Framingham he was greeted by a drum corps and treated to dinner. He reached Worcester at midnight, where a sheriff arrested him for another unpaid debt. Two strangers offered to guarantee his promise he’d repay that debt in two months.

Through the rain and snow he trudged, accepting food from people along the way. In Brookfield, Mass., a brass band greeted him and a cannon fired to salute him. Outside of Hartford he sprained his ankle. Twelve miles out of Philadelphia he realized he took the wrong road. In Maryland he was delayed by toll roads, which required him to raise tollkeepers out of bed to open the toll gates. Thirty miles outside of Washington the horse refused to go on, and he wasted time looking for a fresh horse.

Edward Payson Weston, Celebrity

Edward Payson Weston arrived in Washington at 5 pm on March 4, 1860, four hours and 12 minutes longer than 10 days.

Though he didn’t make it in time, he met members of Congress, First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln and the president, who offered to pay for his return trip. He declined, saying he wanted to walk back in less than 10 hours. He changed his mind after the war started and riots broke out in Baltimore. Instead, he donned a disguise and offered to deliver 117 letters to the Massachusetts and New York regiments – walking of course. He ended up getting arrested by the troops and kept in custody until he proved who he was.

Weston would win prizes for walking from Portland, Maine, to Chicago, lecturing on the benefits of walking before and after. He toured Europe for eight years. In 1869 he walked 1,058 miles through New England in 30 days. In 1871, he walked 200 miles around St. Louis – backwards. At 67, he walked from New York to Philadelphia in less than 24 hours.

He kept on going. At 68, he walked from Maine to Chicago in 24 hours less than he had in his 20s. In 1913, he walked from New York to Minneapolis in 51 days.

Weston’s walking career – and walking – ended in 1927 when a taxicab struck him in New York City. He never walked again and died two years later.

With thanks to A Man in a Hurry: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Edward Payson Weston, the World’s Greatest Walker by Nick Harris, Helen Harris and Paul Marshall. This story was updated in 2022.