The Back-to-Africa movement began with a wealthy mixed-race Quaker named Paul Cuffe. He brought African-American Bostonians to a Sierra Leone colony in 1815, two years before the founding of the American Colonization Society.

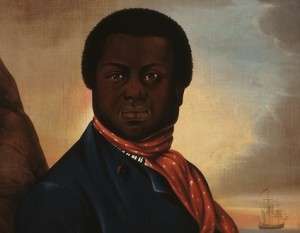

Paul Cuffe led an extraordinary life. He was born on Jan. 17, 1759, on Cuttyhunk Island off the Massachusetts coast, the seventh of 10 children. His mother, Ruth Moses, was an Aquinnah Wampanoag Indian. His father, Kofi Slocum, was a black freedman who at age 10 was kidnapped from his Ashanti tribe in west Africa. Slavers took him to Newport in the colony of Rhode Island, and from there a Quaker who lived in Dartmouth, Mass. enslaved him. His name, Kofi, was corrupted to Cuffe.

Quakers

In 1733, the Nantucket Quakers denounced slavery, the first Society of Friends in the American colonies to do so. They were close to the Dartmouth Quakers, and as a result Paul’s father was freed. Paul’s mother and father raised their 10 children in the Quaker religion.

Paul’s father was a farmer, fisherman and carpenter who taught himself to read and write. He owned his own home and a 116-acre farm. When Paul turned 13, his father died, and Paul and his brother David took over the farm and support for the family. Paul then changed his last name from Slocum to Cuffe, and all but one of his brothers and sisters did.

Paul knew little more than the alphabet but wanted an education and to go to sea. Living near New Bedford, the center of the whaling industry, made that possible. The ocean held the promise of economic opportunity for African-Americans, but also the danger that pirates or slavers would kidnap them and sell them into slavery.

At 16, Paul Cuffe signed onto a whaling ship, beginning an extremely successful life at sea. He moved onto cargo ships, where he learned navigation. In 1776, the British took him prisoner by the British – at age 17 — and held him for three months.

Studying and Saving

Paul Cuffe returned to his family farm when the British released him, and resumed studying and saving. In 1779, he and his brother built a small boat with which they traded among the Elizabeth Islands. Pirates waylaid him and stole his cargo on a trip to Nantucket. It wouldn’t be the last time.

At 21, Paul Cuffe refused to pay taxes because he didn’t have the right to vote. In 1780, Paul Cuffe, his brother and five African-Americans asked the county to end such taxation without representation. In the end he got his taxes reduced.

Paul’s trading began to make him money, and he expanded his shipbuilding business. He bought another ship and hired a crew, while building larger ships. At 24, he married Alice Pequit, who, like his mother, was an Aquinnah Wampanoag Indian. They settled in Westport, Mass., and had seven children.

Eventually he owned a fleet of ships, including the 268-ton Alpha and the 109-ton brig Traveller. He traded up and down the Atlantic Coast, in the Caribbean and Europe.

“The Paul Cuffe Farm” in Westport, Mass., was thought to have been built by Paul Cuffe, and it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Subsequent research showed he probably never owned it.

In 1799 Paul Cuffe bought a 140-acre waterfront property in Westport and built a house. He was by then the richest African-American and Native-American in the country. He was also the country’s largest employer of African-Americans. A devout Quaker, he would later make a substantial contribution to rebuilding the Westport Friends’ Meeting House.

By then he had also decided that Americans of color would never achieve equality with white Americans. He decided their best hope was to return to Africa, and he embraced the nascent movement to colonize Africa with American blacks.

White House Visit

Paul Cuffe became the first free African-American to visit the White House after a ship and cargo from Sierra Leone were seized by U.S. Customs in Newport, R.I. The War of 1812 was approaching, and Cuffe had violated the trade embargo of 1807. He went all the way to the White House to get his cargo back.

Cuffe met with President James Madison, who greeted him warmly. Madison wanted to know about his visit to Sierra Leone and asked him what he thought about African-Americans settling the new British colony. Cuffe persuaded the president he broke the embargo unintentionally, and Madison ordered his cargo and ship returned.

Sierra Leone

In 1787, the British founded a settlement for poor English black people in Sierra Leone, called the Province of Freedom. Five years later, black Loyalists from Nova Scotia (including George Washington’s former slave Harry Washington) arrived. They had petitioned to be moved to Africa as they found Canada’s climate too harsh. Sierra Leone then became a British Crown colony in 1808.

Paul Cuffe had a dream: to establish a prosperous colony in Africa. He wanted to send one ship every year to Sierra Leone with African-American emigrants. They would then produce exports to the United States.

He had launched two expeditions to Sierra Leone in 1811 with an all-black crew. In Africa he established a trading society for the colonists called the “Friendly Society of Sierra Leone.” In 1812, he went to Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York to recruit members and support from the free black community for his African Institution to promote emigration.

In 1815, Cuffe brought 38 colonists, mostly Bostonians, to Freetown, Sierra Leone. Cuffe paid for some of the passengers’ fares and fronted a year’s worth of provisions. His cargo was heavily taxed. In the end, the voyage cost him $8,000. Perhaps even worse, the immigrants weren’t greeted warmly, as the governor was having problems with the colonists. The men had to swear an oath of allegiance to the Crown, and many refused fearing they’d end up getting drafted.

The Dream Dies

He ran into financial difficulties, though. The well-funded American Colonization Society also overshadowed his efforts. Founded by Robert Finley of New Jersey, it brought groups of African-Americans to Liberia. The Society asked Cuffe for his help, but the blatant racism of some of its members alarmed him.

Worse, the African-American community started to question the Back-to-Africa movement. In 1817, his Philadelphia friend, black sailmaker James Forten, wrote to Cuffe to tell him several thousand black men had met at the Bethel African American Methodist Episcopal Church.

“Three thousand at least attended, and there was not one soul that was in favor of going to Africa. They think that the slaveholders want to get rid of them so as to make their property more secure,” Forten wrote. Then, later, Forten signed a statement renouncing the movement and disclaiming any connection with it.

Paul Cuffe died a month later, on Sept. 7, 1817. He left an estate worth $20,000. His last words were, “Let me pass quietly away.”

Image of the Paul Cuffee Farm By Cortikal – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26896927.

The Paul Cuffe Farm in Westport, Mass., is a National Historic Landmark. This story updated in 2022.