In the days leading up to March 17, 1776, Massachusetts was on edge. British troops, under siege for nearly a year, prepared to leave Boston. The people had many worries. Would the British commander, Gen. William Howe burn the city? Would he plunder it? Or would he change his mind and stay? But few if any suspected a British plot to poison Boston.

The British army, hemmed in by rebel cannons, had decided to yield its position and flee to Halifax. Howe and American general George Washington had reached a tacit agreement. So long as the British could leave unmolested, they would not destroy Boston.

The Plot To Poison Boston

But Howe began losing control of his troops. The general had tried to create an orderly process for seizing citizens’ goods the military could use. The soldiers had to issue receipts and certificates for future payment. However, others saw this as a sign that he condoned looting.

Soldiers began plundering stores and homes for anything of value they could find. Frustrated, Howe issued a proclamation:

“The commander-in-chief finding, notwithstanding former orders that have been given to forbid plundering, houses have been forced open and robbed, he is therefore under a necessity of declaring to the troops that the first soldier who is caught plundering will be hanged on the spot.”

“The commander-in-chief finding, notwithstanding former orders that have been given to forbid plundering, houses have been forced open and robbed, he is therefore under a necessity of declaring to the troops that the first soldier who is caught plundering will be hanged on the spot.”

Washington, meanwhile, waited impatiently for the British to depart. Concerned that Howe might be stalling while reinforcements arrived, Washington ordered his troops to continue building fortifications. On March 17, however, the British finally made good on their plans. An armada of ships, loaded with more than 9,000 soldiers and more than 1,000 loyalists, made their way to sea.

Dr. John Warren, whose brother Joseph had perished at Bunker Hill, made an assessment of the town after the British fled.

“The houses I found to be considerably abused inside, where they had been inhabited by the common soldiery, but the external parts of the houses made a tolerable appearance. The streets were clean, and, upon the whole, the town looks much better that I expected. Several hundred houses were pulled down, but these were very old ones.”

The Damage Done

The story in Charlestown, which the British had burned, was different. Almost nothing still stood, Warren reported, save for an occasional wall or chimney.

Other parts of Boston also bore the marks of the British occupation while under siege.

The British had turned the Old South Church into a riding school for officers. They had dragged Deacon Hubbard’s ornate pew outside and converted it to a hog sty. The parsonage was pulled down and burned for fuel, as was the Old North Chapel, dating to 1677, the steeple of the West Church and Boston’s celebrated Liberty Tree.

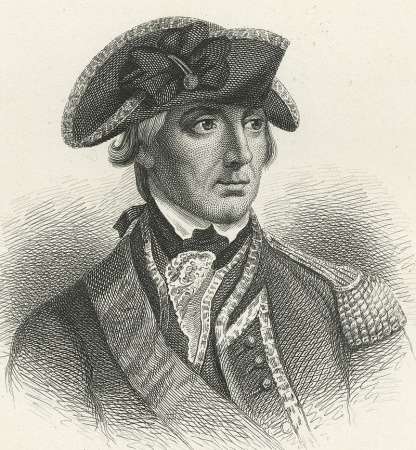

William Howe

The Common was disfigured and fortified, and Faneuil Hall fitted out as a theater, Warren noted. What cannon the British could not remove with them had been spiked (for the most part) and shells split and shot dumped into the harbor. The Americans would repair and recover much of what had been abandoned.

In total, damage amounted to £323,074. Washington informed John Hancock that the British officers who occupied his opulent home hadn’t harmed it. Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John, describing their house as “very dirty, but no other damage has been done to it.”

Shocking Discovery

But what Warren and fellow physician Dr. Samuel Scott found in the British medical supplies shocked them the most. In a workhouse used as a hospital, Warren discovered a cache of medicines. They could be highly useful in treating soldiers or citizens. However, Scott found that, upon leaving, the British had mixed arsenic into the medicines. He provided an affidavit to the Legislature.

“I, John Warren, of Cambridge, physician, testify and say, that on or about the twenty-ninth day of March last past, I went into the workhouse of the town of Boston, lately improved as a hospital by the British troops, stationed in said town,” he wrote.

In one room they supposedly used to store medicine, “I found a great variety of medicinal articles lying upon the floor,” he wrote. They’d packaged some and scattered the rest on the floor, he wrote.

Dr. John Warren by Rembrandt Peale, Harvard University Portrait Collection

“Amongst these medicines, I observed small quantities of what, I supposed, was white and yellow arsenic intermixed; and then received information from Dr. Daniel Scott that he had taken up a large quantity of said arsenic from over and amongst the medicine,” wrote Warren. He then described how Scott had collected it chiefly in large lumps and secured it in a vessel.

A Shocker

Warren then asked Scott to let him see the arsenic. He did, and Warren judged the lumps of arsenic to weight 12 to 14 pounds. Surprised, he looked at the medicine carefully. He judged them as popular and useful — without the poison.

“I advised Dr. Scott to let them remain, and by no means meddle with them, as I thought the utmost hazard would attend the using of them,” he wrote. The medicine stayed there.

This shocking news reached Massachusetts via the newspapers, and as the horror of the British plot to poison the returning colonists sank in, so did its significance as a propaganda weapon.

The affidavit was quoted and distributed throughout the colonies. It served as a useful message to reinforce public antipathy toward the British.

Thanks to History of the Siege of Boston by Richard Frothingham and The Siege of Boston by Allen French. This story was updated in 2023.

2 comments

[…] British Tried to Poison Patriots in 1776 […]

[…] the Siege of Boston, Thomas smuggled his printing press out of town and settled in Worcester. There he published the […]

Comments are closed.