You might suppose the Federal Reserve banking system was begun in response to the great stock market crash of 1929, but it wasn’t. The system has its roots in the financial panic of 1907, caused by a Maine man whose wealth was only exceeded by his ambition – and tragically so.

Charles W. Morse of Bath, Me. had many titles. Ship builder, banker, freight magnate. But it all started with ice.

Cartoon of J.P. Morgan taking over the banking industry following the panic of 1907.

Morse’s father and grandfather were both towboat captains on the Kennebec River. They did a lively business in pulling ships up from the busy port at Bath to points inland on the river, an important trade corridor for Maine.

One of the products that Maine exported to the rest of the world, along with lumber, was ice. Ice houses dotted the banks of Maine river towns. During the long winters, men would cut and harvest ice, pack it in the ice houses and ship it south to the cities in the summers where it was in great demand.

Charles Morse

Charles Morse’s father and grandfather taught him the first lesson that would direct his business career: the value of monopoly. Despite occasional challenges, the Morses managed to control the lion’s share of the freight towing business on the Kennebec.

Morse’s father gave his son a salary to become bookkeeper at the towing company. Part of the Charles Morse legend is that he took the $800 salary and immediately hired someone for $300 to do the actual bookkeeping while he attended Bowdoin College.

All the while Morse made a study of the shipping business. In addition to towing freight on the Kennebec, the Morse family invested its money in the schooners that ran up and down the coast hauling coal and other freight in the coasting trade.

What particularly interested Morse was ice. He saw an opportunity to take advantage of any ship that had arrived in Maine carrying coal and then headed on a return trip empty. It could be filled with ice to drop off on its return trip, he realized, and he soon was making a tidy profit off his shipping of ice.

Kennebec Ice

Morse was by no means the first person to see the value of ice from the Kennebec, which had been shipped south since well before he was born. But he did see the potential in creating a monopoly in it. Gradually Morse purchased the ice houses on the Kennebec. During a cold summer when ice was cheap, he would buy the ice houses from men who were tired of the business, adding to his empire.

By 1900, he had become the “Ice King.” Morse reached this pinnacle thanks to his ability to marry together the vagaries of stock markets, politics, shipping and ice. His company issued stock and used the proceeds to fund its expansion. He was perfectly positioned in 1896 when the eastern United States was hit with a 10-day heat wave that had unprecedented effects. Thousands of people died and the price of ice rose to new heights.

Heat Wave

Morse moved to New York City. In the wake of the 1896 heat wave, the city was in a panic to prevent a repeat of the carnage it caused, and ice was the answer. Morse offered to share the wealth with the leaders of the city’s Tammany Hall political operation and soon the price of ice was fixed to his liking.

Political guile and stock manipulating skills helped him corner the market on New York ice. It didn’t hurt that he also knew the tow boat business. When his competitors’ deliveries were hampered by the vagaries of tide and wind, Morse towed his loads of ice into New York Harbor and up the river for distribution.

Morse’s price fixing and stock manipulation schemes eventually caused great controversy. Reformers railed against him for using political connections to fix the price of ice. Shippers and independent ice producers accused him of forcing them to sell at desperately low prices if they wanted to access the city markets where he held control.

By 1901 when he more or less exited the ice business, Morse’s name was tarnished but not his finances. He had accumulated more than $12 million. He set his sites on an even bigger monopoly: freight.

Conquering Freight

Over the next seven years, Morse would consolidate ownership of nearly all the freight shipping lines on the east coast. Morse had a simple formula for his acquisitions. He would buy a controlling interest in a bank, and borrow money from it. With the borrowed money he would buy stock in the steamship company. The bank would hold the stock as collateral for the loan, and he was left in control of the company.

As long as stock prices went up, Morse’s arrangements worked perfectly. In the months prior to the panic of 1907, Morse seemed poised for success. With one eye-popping purchase of a steamship line controlled by J.P. Morgan – for $10 million – Morse put together his Consolidated Steamship Company.

With one or two exceptions, anyone wanting to ship anything to any city between the northern tip of Mane and New Orleans would have to pay a Morse steamship. The goose seemed finally right for the plucking.

But there were two key differences between Morse’s experience in shipping and his ice business. There was no heat wave to drive the price of shipping higher. And he had not purchased his shipping companies on the cheap as he had his ice houses. While he could fix the price of shipping he could not ensure demand, which began faltering thanks to a recession.

Had he been able to maintain his monopoly for a few years, Morse might have weathered whatever economic cycles came his way and prospered as inflation improved the value of his assets. But that’s not what happened. Instead, an obscure investment would prove his undoing.

Augustus Heinze

The financial panic of 1907 started with Charles Morse’s decision to invest in copper mining. One of his investment partners was a man named Augustus Heinze. A brash risk-taker, Heinze had made a small fortune in copper mining.

Heinze had managed to get the better of H.H. Rogers and John D. Rockefeller of Standard Oil, then assembling a monopoly on American copper mines under the umbrella of Anaconda Copper. Heinze had a small mining company, United Copper. But his real strength lay in understanding the laws that governed mining in Montana.

A miner whose claim followed a vein of copper that led underneath his neighbors’ land was allowed to mine that vein wherever it led. So even with a relatively small footprint on the ground, Heinze terrorized the neighboring mines.

Heinze’s competitors grew fed up with his tactics and bought him out. He left Montana for New York with $12 million in his pocket.

Copper and the Panic of 1907

Heinze and Morse teamed up. Between them they had partial control of six national banks, 10 state banks, five trust companies and four insurance companies. With the formidable pile of cash these institutions held, the two decided to take a fling on copper stocks.

They then amassed an enormous holding in United Copper stock, the company Heinze helped build. Working with Heinze’s brother Otto, Morse and Heinze devised a scheme to corner the market in the stock.

With intelligence from their banking holdings, Morse and Heinze believed that many investors were selling the stock short. In other words, they would borrow shares to sell at the present price – say $35 – with the expectation that they could then buy more shares at a lower price – say $10 – to replace the ones they had borrowed. The short seller would pocket the difference and make out well.

Morse and Heinze believed they controlled so much of the stock the short sellers wouldn’t be able to find any stock to replace their borrowed shares. They would then have to buy from Morse and Heinze at whatever price they demanded.

The Panic of 1907 Starts with a Whimper

Through the summer of 1907, the plan seemed work as the prices of United Copper shares continued increasing. As rumors of the squeeze made the rounds on Wall Street, speculators jumped in driving the price of shares ever higher, peaking at $60. Some short sellers took their losses and closed out their positions.

But by late October, the of United shares began to falter. Large blocks of stock came onto the market. Most likely H.H. Rogers and his Rockefeller friends sold the shares – quite possibly at a loss. They had not forgotten Heinze and were happy to assist in collapsing his scheme. Using friendly reporters, the Standard Oil group circulated the story that the Heinze/Morse scheme to corner the market in United Copper shares had failed.

With the price of United shares plummeting, Morse’s banks started to look shaky. Depositors began demanding their money. For several days Morse was able to prop up the banks, but one by one the dominoes began falling.

Morse was forced out as director at his banks and trust companies, and they turned to J.P. Morgan for help. Would he help prop them up? He would not. He preferred to see Morse, his old adversary in the shipping business, collapse. By the time Morgan finally relented and helped recapitalize some banks, making himself an enormous profit, the panic of 1907 had crippled the entire world’s economy.

Prison and Beyond

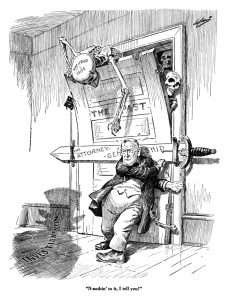

1922 political cartoon of attorney general Harry Daugherty showing the skeleton of the Morse scandal escaping the closet.

Morse’s shipping company would wind up in receivership. And Morse, the ice king, would wind up in federal prison in Atlanta for violating the banking laws. Sentenced in 1910, he would soon con his way out of prison.

Morse paid future attorney general Harry Daugherty $50,000 to plead his case with President William Howard Taft. Morse suffered from tuberculosis, he told Taft, and would die if not released. Taft pardoned Morse in 1912. The poor man only had a year or so to live, the public was told. Later the con was revealed.

Morse finally died in 1933, but not before one final run at business. In 1916 he used the remnants of his steamship company to establish several shipyards to build government ships for World War I.

He later went to trial for war profiteering, but avoided conviction. He did forfeit $11 million to the government in a civil suit.

Morse died in 1933 in Bath, Me., the same city where his legend started. His greatest legacy is the 1913 Federal Reserve Act that established the system of federal reserve banks designed to prevent the banking system from collapsing as it did in the panic of 1907.

This story was updated in 2021.

2 comments

[…] he saved the federal government from default in 1895 and bailed it out 12 years later, ending the Panic of 1907. He headed an interlocking series of trusts that controlled many of the major industries in the […]

[…] the political tide that originally carried Bryan to prominence was the fallout from the financial panic of 1893. With America wrestling with a depression, two elements fought to control American monetary policy. […]

Comments are closed.