In 1820 at the age of 78, Thompson Maxwell rode his horse more than 1,600 miles from Detroit to New England and back. He did it to revisit some of the most important sites of the American Revolution. After all, he’d fought at most of them.

He was there when patriots dumped tea into Boston Harbor (though whether he dumped it himself is a question for historians to resolve). He fought in the Battle of Concord and then at Bunker Hill.

And that’s only part of Thompson Maxwell’s story. He also fought in the French and Indian War as a teenager, helped suppress both Shay’s and Pontiac’s rebellions as a young man and fought in the War of 1812 as a septuagenarian. All told, he saw action in 22 battles.

He may have embellished his tales a bit, but his life follows the arc of American history from the colonial wars to the settling of the west.

Thompson Maxwell

He was born in Bedford, Mass., in 1742 to an Irish immigrant couple, the youngest of seven children. His mother was 50 when he was born, and may have had a hard time disciplining her youngest son.

At the age of 15, Thompson ran away from home to fight in the French and Indian War. He followed his older brother Hugh, known as a “brave and useful soldier.” Brother Hugh escaped from the French after they captured Fort William Henry on Lake George.

Thompson fought under two Revolutionary heroes, John Stark and Israel Putnam, and for a time he fought Indians with the celebrated Rogers’ Rangers. He recalled the fall of Montreal, with, “colors flying, drums beating, drills and camp display in martial splendor.”

He couldn’t get enough of marching, hardship and danger. In 1762 he went to Detroit to quell Pontiac’s rebellion. When he came home he married Sybil Wyman, and they moved to Amherst, N.H. Eventually, the couple had five children.

Boston Tea Party

Thompson Maxwell farmed and teamed – that is, hauled goods in a wagon. A trip to Boston in 1773 brought him to the Boston Tea Party. As an old and revered Revolutionary War veteran, Thompson Maxwell dictated his memoirs several times.

He gave several accounts of how the tea was thrown overboard.

“Seventy-three spirited citizen volunteers, in the costume of Indians, in defiance of royal authority, accomplished the daring exploit, John Hancock was then a merchant,” he said. “My team was loaded at his store for Amherst, N.H., and put up, to meet in consultation at his house at 2 p.m. The business was soon planned and executed. The patriots triumphed.”

In another memoir, he claimed he had joined the Indians and dumped the tea along with them.

Historian J.L. Bell believes he was in Boston on Dec. 16, 1773, but only watched the party and picked up some gossip. He had some inside information that participants likely knew: that shipowner Francis Rotch planned to take his tea back to England, that John Hancock organized the raid and that George Robert Twelve Hewes was one of the leaders. On the other hand, he got some details wrong, claiming the “Indians” dumped the tea at Long Wharf, when it happened at Griffin’s Wharf.

American Revolution

Then on April 18, 1775, Thompson Maxwell drove to Boston with his team of horses, and went on to Bedford to stay with his sister and brother-in-law. That’s how he ended up at the Battle of Concord, said to be the only New Hampshire soldier there.

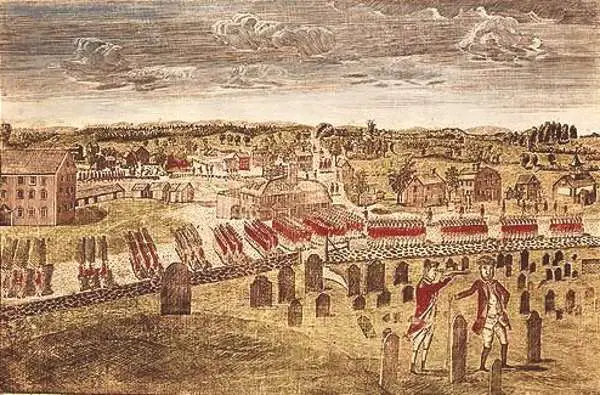

Afterward, he probably went back to Amherst to join his company as a second lieutenant. The company then marched to Boston to fight the Battle of Bunker Hill. Thompson described how he drove stakes to reinforce the hill and stuffed hay between fence rails. During the battle, the British shot his brother Hugh in the right arm, but Thompson got through it unscathed.

Thompson Maxwell remembered Washington arriving to take command of the Continental Army. He fought with John Sullivan at the Battle of Trenton on the day after Christmas, and he marched on to capture Princeton. He saw action at the Battle of Bennington, which defeated Gen. John Burgoyne’s forces. “Grand military display,” he said. “Resigned and went home.”

You’d think he’d had enough of fighting by then, but no, he and his brother Hugh fought to put down Shay’s Rebellion.

Finally he did have enough, and spent 20 years farming in Buckland, Mass. But he still served his country, representing Buckland at the Massachusetts constitutional convention.

Thompson Maxwell, Old Soldier

Thompson Maxwell moved to Ohio in 1800, and his wife died two years later. He saw action against Indians at the Battle of Tippecanoe, when he had reached his late 50s. In 1807, he married a widow, who died six years later, and then he married again.

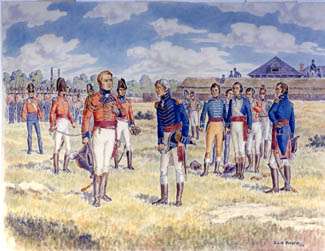

During the War of 1812, he raised troops and served in the army as a major. But he got no military glory this time. He guided Gen. William Hull to Detroit, but Hull later surrendered the fort to the British. The British captured Maxwell along with the others, but paroled him because of his age — 67.

He received a nasty welcome at home. He later described what happened:

“A mob, irritated by Hull’s pusillanimity, misjudging my patriotic efforts, and denouncing all parties concerned in the late disasters at Detroit, rally and gather about my habitation, burn my house, destroy my property, and, barely clothed, I escape for my life through a corn-field by night. . . .”

He ignored his friends’ advice against rejoining the army, and got captured again as well as wounded. Finally he ended his military career as barracks master in Detroit.

Perhaps he kept rejoining the army for money. Indigent veterans didn’t receive pensions until 1818. His brother Hugh, for example, was broke, and tried to restore his finances by selling horses to the West Indies. Hugh died on the voyage.

Thompson Maxwell died in 1832 at the age of 90 near Detroit.

* * *

Coming soon from the New England Historical Society: Your guide to the historic sites that bring the American Revolution to life. Click here to preorder your copy.

This story was updated in 2024.