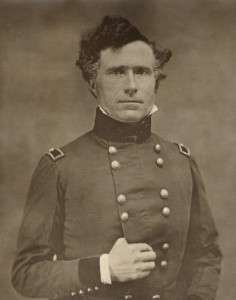

In 1852, Nathaniel Hawthorne did the unthinkable: He wrote a campaign biography for presidential candidate Franklin Pierce.

Critics thought such hackwork beneath Nathaniel Hawthorne. He was, after all, the acclaimed author of The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables.

Nathaniel Hawthorne didn’t care. He had befriended Pierce during their student days in the 1820s at Bowdoin College, and he would be loyal to him until the end.

Pierce ran for president of the United States as a Northerner sympathetic to the South. As president, he appointed Nathaniel Hawthorne as the U.S. consul in Liverpool, a plum job that paid him well to do little so he could continue his writing.

Nathaniel Hawthorne Stands By His Man

Four years later, Pierce left office as one of the most reviled ex-presidents in history. He had tried to unify the North and South, but drove them further apart. Most of his friends, neighbors and political allies abandoned him, though Hawthorne never did.

While serving as consul in England, Hawthorne had traveled the countryside. He wrote a series of sketches called Our Old Home. Back home on July 2, 1863, he wrote the book’s dedication to Franklin Pierce.

It read, in part,

…it rests among my certainties that no man’s loyalty is more steadfast, no man’s hopes or apprehensions on behalf of our national existence more deeply heartfelt, or more closely intertwined with his possibilities of personal happiness, than those of FRANKLIN PIERCE.

His publisher, James T. Fields, begged him to leave it out. Nathaniel Hawthorne replied, “if he is so exceedingly unpopular that his name is enough to sink the volume, there is so much the more need that an old friend should stand by him.”

Hawthorne’s friend Ralph Waldo Emerson ripped out the dedication before putting the book on his library shelf.

White Mountains

Months later, Pierce’s wife Jane died. Nathaniel Hawthorne stood by the side of the lonely, grieving ex-president as she was laid to rest. Pierce noticed Hawthorne seemed in ill health and adjusted his collar to keep him warm.

In the spring of 1864 Nathaniel Hawthorne decided a trip to the White Mountains in New Hampshire would be good for his health. Pierce agreed to go with him. Hawthorne’s wife Sophia told the ex-president he needed help getting in and out of carriages because of his weak eyesight and uncertain steps.

The two friends left Boston together and traveled to Pierce’s home in Concord, N.H. They went to Dixville Notch once the weather was good enough.

On May 18, 1864, they returned through Plymouth. They turned in at the Pemigewasset Hotel, on the site of what is now the Plymouth Regional Senior Center and the Gadd block.

Nathaniel Hawthorne took a nap, ate a bit of food and drank a cup of tea before going to bed. Pierce, in a letter four years later, described what happened next.

The Death of Hawthorne

“Passing from his room to my own, leaving the door open and so placing the lamp that its direct rays would not fall upon him and yet enable me to see distinctly from my bed, I betook myself to rest too, a little after ten o’clock,” he wrote.

“But I awoke before twelve, and noticed that he was lying in a perfectly natural position, like a child, with his right hand under his cheek. That noble brow and face struck me as more grand serenely calm then than ever before. With new hope that such undisturbed repose might bring back fresh vigor, I fell asleep again; but he was so very restless the night previous that I was surprised and startled when I noticed, at three o’clock, that his position was identically the same as when I observed him between eleven and twelve.

“Hastening softly to his bedside, I could not perceive that he breathed, although no change had come over his features. I seized his wrist, but found no pulse; ran my hands down upon his bare side, but the great, generous, brave heart beat no more.”

The body of Nathaniel Hawthorne was returned to Concord, Mass., where he was laid to rest. His pallbearers included Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier and Louis Agassiz.

Franklin Pierce was not among them.

With thanks to Dead Presidents. You can read more about Hawthorne’s milieu in Concord — their lives, their loves and their work — in American Bloomsbury by Susan Cheever. This story about Nathaniel Hawthorne and Franklin Pierce was updated in 2024.

8 comments

It was A. Bronson Alcott, not his daughter Louisa May, who served as one of Hawthorne’s pallbearers.

[…] Franklin Pierce and Nathaniel Hawthorne Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlett Letter remains widely read today. His 1852 book The Life of Franklin Pierce is a bit less so. The two had been friends since their school days and would literally be close for the rest of Hawthorne’s life, as Hawthorne emerged as a brilliant author and Pierce unexpectedly became President. We at Made Man are fascinated by Pierce, who boasted great hair and lived the grimmest life of all our presidents. His miseries included his own party refusing to let him seek reelection, watching all three of his children die before age 12 and alcoholism. (If you want to feel better about yourself, study Franklin Pierce.) Ironically, Hawthorne dealt his dear friend another tragic blow as, in a twist far too horrible for fiction, Pierce was the one who discovered his dead body. […]

[…] said Pierce’s close friend Nathaniel Hawthorne didn’t mind that he was never invited him to the White House because his wife was so […]

[…] his support for the Confederacy. He was shunned for the rest of his life, though his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne stood by […]

[…] the news was more mundane. Nathaniel Hawthorne described the town crier in Salem, Mass., in his Twice-Told […]

Reiterating the above comment: The pallbearer was Bronson Alcott, absolutely not Louisa May Alcott.

[…] and England, where her father served as U.S. consul general to the British government. His friend President Franklin Pierce appointed him to the […]

[…] Nathaniel Hawthorne, posted as U.S. consul in Liverpool during the famine years, compared the Irish emigrants to maggots. His friend Herman Melville thought Liverpool the worst seaport in the world. It, […]

Comments are closed.