In the depths of winter or in a far-away clime, the very word “clambake” may bring a tear to a New Englander’s eye. To the Yankee, clambakes epitomize carefree summers at the shore, sunshine and salt air and the camaraderie that attends a massive pigout on steamed seafood.

The clambake requires four elements: firewood, rocks, rockweed and a work ethic. The clambake master digs a hole on a beach. He or she lines it with rocks, preferably flat, and then fills it with firewood—perhaps driftwood gathered from said beach. The fire then burns for several hours. When it burns out, shovel off the ashes, layer rockweed onto the rocks and then pour on the goodies: clams, lobster, fish, sausage, corn on the cob, potato, onion. Cover with more rockweed and then top with a tarpaulin soaked in saltwater. When it smells done, about an hour and a half later, take off the tarp and the seaweed. Ring the dinner bell.

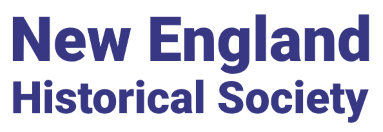

A Rhode Island clambake

To clear up any misconceptions about the clambake, here are seven fun facts about that sublime New England ritual.

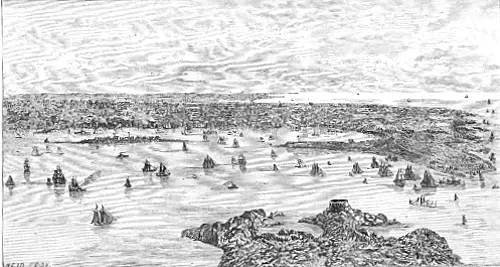

1. Narragansett Bay is the epicenter of the clambake.

They began in the early 19th century as small events at picnics, fairs and grange meetings, possibly in Rhode Island. The first mention of a clambake in a cookbook called it a “Rhode Island Clam Bake.”

The commercial clambake probably began in Warwick at a place called Buttonwoods or Buttonwoods Beach. A family registered with the Narragansett tribe, the Kinnecomms, held clambakes on the beach for paying customers. They were said to have served thousands in 1840 for a William Henry Harrison rally for president.

A clambake on Narragansett Bay

After the Civil War, more resorts and seaside communities grew up along the Bay — places like Hunt’s Mills, Kettle Point, Squantum Point, Ocean Cottage, Silver Spring, Cedar Grove, Camp White, Crescent Park, Portsmouth Grove and Sakonnet Point on the east shore, and Field’s Point, Rocky Point, Oakland Beach and Buttonwoods on the west.

They lured paying visitors with clambakes, typically on a Thursday. A typical Rhode Island clambake or shore dinner consisted of a white potato, sweet potato, corn, onion, sausage link, piece of fish, 30 steamer clams, lobster, watermelon, six littlenecks on the half shell and a bowl of quahog chowder.

2. Natives did not invent the clambake.

When the American public embraced the colonial revival, it began to view the clambake as part of the New England founding myth. Though Philadelphia, New York and Cleveland held clambakes, they became a New England icon.

According to the creation myth, the first settlers approached the shores of Massachusetts and saw steam rising from the Native clambake on the beach.

Um, not really. Natives did bake clams, but not with all the fixings. On Nantucket, for example, they put quahogs side-by-side on the ground, applied burning coals to their backs and ate them after a few minutes.

Clambake at Seaside by Winslow Homer

But historians have found no evidence that Natives combined lobster, potatoes and other comestibles into what we call the clambake.

Robert P. Tristram Coffin asserted in his 1944 book, Main Stays of Maine, that only the “effete and degenerate” commit the unpardonable sin of mixing food. Coffin then waxed elegaic about the Abenaki way of cooking clams. They did it “in the open, under the whole high blue and blazing Summer sky.”

For the fire, Coffin advised, “collect the spars and ribs, rimy with salt, from ancient ships, driftwood turned to sabs of sheer silver by the tide and the wind, wood that has come in from far places over the sea.”

The poetry continues. “When the blaze falls, and you have rubies and topazes of living coals left a foot deep, throw yourself into the flooding tide and dredge up armfuls of rockweed.” Tear it out by the roots, and “heave the green sprays with blossoms of orange balloons growing on them upon your bed of coals.” When the rockweed reaches a depth of six inches, pour on your bushel of clams. throw on more rockweed and cover them over. Sit down and let her steam.

Coffin concluded, “That tender small clam tastes like the elixir of life.”

3. 19th century clambakes were huge.

Before the automobile took over, people traveled to leisure destinations en masse – by steamboat, trolley or railroad. Once they arrived, they stayed in one place. Clambakes could serve large numbers of people outdoors on tables that were simply long wooden planks covered with butcher paper. Some had pavilions by the beach.

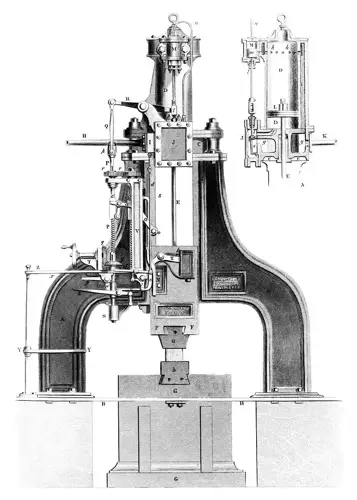

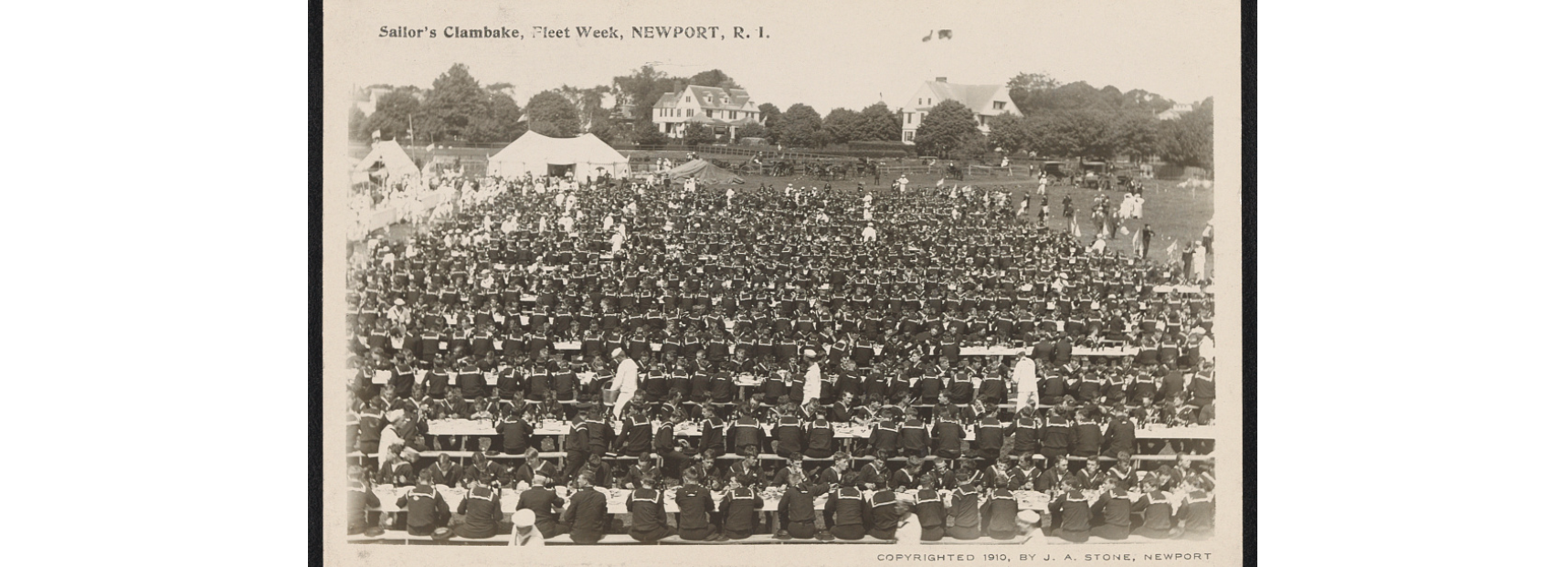

Rocky Point Clambake House

In New Bedford, Lincoln Park, which opened in 1893, had a clambake pavilion that seated hundreds at a time.

Rocky Point in particular won renown for its enormous clambakes. Its shore dinner hall seated 2,500 people, but crowds still formed long lines to get in.

The automobile put an end to the mega-clambakes. In 1907, Field’s Point in Providence served 150,000 clambakes in 1907, but only 80,000 three years later. What was left by the Great Depression got wiped out by the Great Hurricane of 1938.

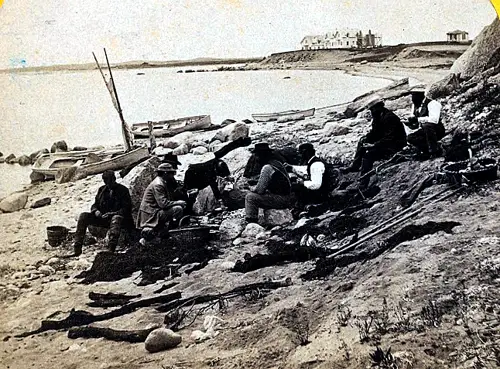

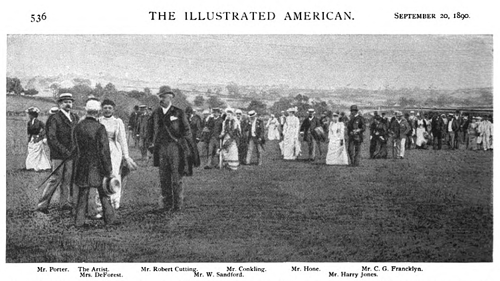

A clambake for sailors in Newport, R.I., during Fleet Week in 1910

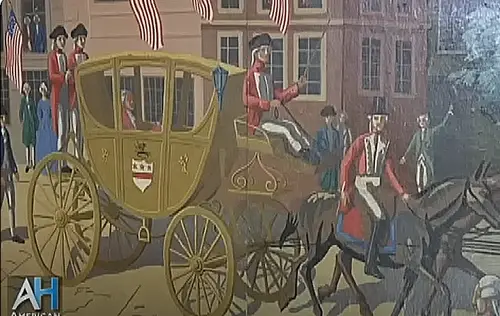

4. Presidential candidates liked (or pretended to like) clambakes.

Horace Greeley, who ran for president in 1872, came to a Silver Spring clambake in Rhode Island on August 6. The New York Herald reported that 10,000 people showed up, waved national flags and listened to a brass band. They filled the beer salons as three huge fires glowed like smelting furnaces under seaweed and tarpaulin as they baked about 10,000 clams.

Greeley arrived to hearty cheers, the Herald reported. People crowded around him, shook his hand and waved hats and handkerchiefs. The clambake started at 2 p.m. Greeley “breasted the beating surf of humanity, and after desperate struggles, succeeded in reaching the dining hall.” He then “went to work upon the bivalves tooth and bait.”

A crowd any politician would love

Prussian professor Anton Siegafritz found the political clambake horrifying. In describing them to the uninitiated, he wrote that they featured speeches, music and song, along with “profuse feasts upon a species of oyster called the clam.

“Vast crowds attend these celebrations, and no sooner are the gorged with the insidious comestible, than they become full of excitement and furores, swear themselves away in fealty to the most worthless demagogues, sign, fight, dance, gouge one another’s eyes out and conduct themselves like madmen in a conflagration.”

5. One is expected to eat clams with gusto and not with a fork.

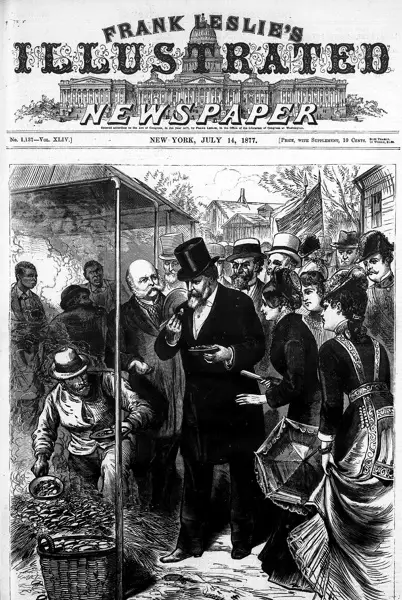

In 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes planned to make history at the Rocky Point Hotel. He would call inventor Alexander Graham Bell on the telephone—the first presidential phone call ever. Instead, he made the unpardonable error of eating a clam with a fork at the clambake held afterward. His gaffe made the front page of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. The newspaper chastised the president for failing to eat the clam like an honest local epicure—with his hands.

Oh, the indignity!

6. The clambake became a thing in Cleveland.

When the railroads came, they carried iced shellfish west to Cleveland, Chicago and beyond.

In Cleveland, wealthy people like the Rockefellers had summer homes in Lake County, just east of the city. After the Civil War, they began to throw clambakes on Little Mountain with huge amounts of food.

The clambake spread beyond Lake County. Typically, they happened in the fall. One writer called it “the period of the expanding belt line.” The average businessman, trade association member, company employee, lodge brother and union member attended at least two or three in a season, he wrote. Halle’s department store held them for employees after World War II. Cleveland mayor Ralph Perk, who served from 1971-77, held clambakes as political fundraisers. (Perk’s wife, Lucille, famously declined an invitation to a White House dinner because it was her bowling night.)

Cleveland Mayor Ralph Perk. Maybe a clam would have cheered him up.

Unlike the New England clambake, the Cleveland version eschews the sand pit, the rocks and the seaweed. Everything just gets thrown into a pot: a dozen clams, half a chicken, an ear of corn and a sweet potato. Add rolls, butter and coleslaw to the menu, plus pies for dessert, and you’ve got a Cleveland clambake. Lately some cooks have added kielbasa to the mix.

If a Cleveland clambake sounds bizarre to you, just remember Cleveland once belonged to Connecticut.

7. Controversy surrounds the Rhode Island clambake clam chowder.

The Rhode Island clambake begins with clam chowder and ends with watermelon. However, Rhode Island Clam Chowder has no milk. Unlike the typical New England Clam Chowder, it has two essential ingredients: quahogs and a clear broth made from onions, clam juice, salt pork, celery, herbs and spices.

Non-Rhode Islanders have long vilified the dairy-free chowder. “It is a kind of vegetable soup, spoiled by a sea-creature whose cooking is a tragic mistake,” wrote Coffin. “There’s a price on Rhode Islanders’ heads in Maine.”

A tomato-based clam chowder

Even worse, Rocky Point clam chowder included the tomato. A cookbook writer in 1940 called it a “terrible pink mixture.”

So noxious was that concoction to a Maine state representative that in 1939 he threatened to file a bill making it illegal to add a tomato to clam chowder. Guilty offenders would have to dig up a barrel of clams at high tide. As any clammer will tell you, that is not only cruel and unusual punishment, but impossible.

He never filed the bill, as a clam chowder contest held in Maine determined the superiority of Maine-style clam chowder.

With thanks to the The Great Clam Cake and Fritter Guide.

Images: Seafood By inuyaki.com – https://www.flickr.com/photos/arndog/3719278633/, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7341831. Rhode Island clambake, Providence Public Library Digital Collection, CC By-SA 4.0. Tomato-based clam chowder By Alexa – Manhattan Clam Chowder, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=46461294.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “House for ‘Clam Bake’ at Rocky Point, R.I.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1850 – 1930. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-aed6-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

in the mid-1850s. The Gorham silver firm – located in Providence, Rhode Island – became the industry leader by the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

in the mid-1850s. The Gorham silver firm – located in Providence, Rhode Island – became the industry leader by the last quarter of the nineteenth century.