In Gilded Age Newport, Rhode Island, an invitation to one of Ward McAllister’s summer picnics could make or break a hopeful social climber.

One contemporary aptly described this era as “an ever-shifting kaleidoscope of dazzling wealth, restless endeavor, and rivalry.”[1] American ideas about class were changing, especially in cities. Old and new money mixed like oil and water. The increase in American fortunes necessitated stricter guidelines for social acceptance. Enter McAllister, a controversial figure who coached this evolving class of insecure millionaires in Old World aristocratic customs.

Ward McAllister

Ward McAllister’s Newport Roots

McAllister held a rapt audience among the exclusive “Four Hundred” in New York, but he held court on Aquidneck Island. Part of his success stemmed from experience. McAllister’s visits to Newport predated the New York crowd by decades. He was so intimately entwined with the city’s 19th-century history that one local newspaper claimed the Georgia-born, world-traveling transplant as “a native Newporter.”[2]

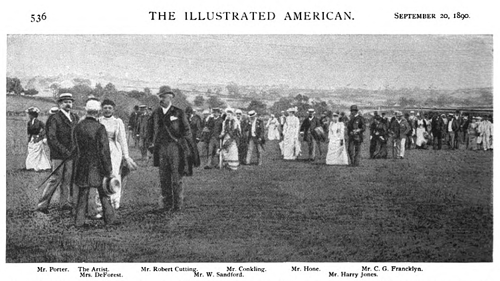

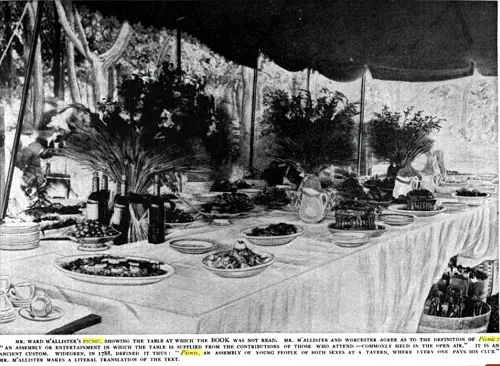

A Ward McAllister picnic at Bayside Farm

McAllister’s childhood summer vacations illustrate a very different kind of Newport — one still on the rise and not yet “the most luxurious and stratified resort in America.”[3] They demonstrate some of the features that attracted early tourists to Aquidneck Island. They also sketch a portrait of a loving extended family, ordinarily scattered hundreds of miles apart, who associated the area with togetherness and refuge. Finally, these summers were formative for McAllister’s later social ascent.

Newport’s “Rise and Fall and Rise” [4]

At the outbreak of the American Revolution, Newport was the fifth largest city in the colonies.[5] As participants in the Triangle Trade, the port city’s merchants made connections with their counterparts in other colonial maritime hubs, notably Charleston. They dealt in molasses, sugar, rum, slaves and other lucrative goods.

The arrival of 10,000 invading British troops changed everything. The Revolution bled Newport of half of its population and most of its prestige. As historian Jon Sterngass notes, “No city seemed less likely to prosper in the first third of the 19th century.”[6]

Yet it did. A newly-independent United States found its footing, and Americans gained the means to travel for pleasure. Wealthy southerners with pre-war connections to and fond memories of Newport returned to the city, rescuing it from a decades-long economic depression. One of these early tourists was Ward McAllister’s grandmother, Sarah Marion Mitchell Hyrne Cutler.

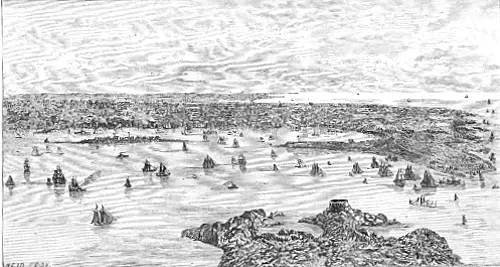

View of Newport

“The Duchess” [7]

Born in 1761, Sarah was no stranger to vacationing in Newport. Joining other prominent South Carolinians, Georgians, and Virginians, the Marions trekked north to enjoy Aquidneck Island’s congenial social scene, natural beauty and cool climate. Newport saw such an influx of southern families seeking reprieve from summer heat and mosquitos that the resort became known as “the Carolina hospital.”[8]

The death of Sarah’s first husband, Dr. Alexander William Hyrne, left her a widow at 20—and a very wealthy one. This tragic event could have cemented South Carolina as her lifelong sphere of influence. However, Sarah’s periodic visits to the Northeast had proved influential, if not fateful.

Sarah Cutler

When Sarah fell in love with Benjamin Clarke Cutler, the sheriff of Norfolk County, Mass., she knew marrying him would mean moving north. Undaunted, she said her vows in Charleston in 1794 and embarked for Boston, where the couple settled happily. They had five children: Mary (called Eliza), Julia, Benjamin, Jr., Louisa and Francis Marion.[9]

“A Meteor-Like Life”[10]

Each of the Cutler children grew up, married, and moved away. Sarah welcomed her children’s spouses with open arms and cherished the births of her grandchildren. However, she lamented that changing circumstances would force her “to lead a meteor-like life by wandering from one star to another” to see her scattered family.[11]

Louisa moved farthest from her Boston home. She married Matthew Hall McAllister, Jr., of Savannah in 1823. A private lawyer when he married, McAllister rose to become U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Georgia in 1827. He also served as a Georgia state senator in 1834 and mayor of Savannah in 1837. Louisa and Matthew Hall McAllister were married for more than 40 years. They had five children: Harriet, Julian, Matthew Hall III, Ward, Francis Marion and Benjamin.[12]

For Louisa, the distance between Georgia and the great cities of the Northeast, where her siblings had settled, seemed interminable. “I wish I did not love you all so much,” she once wrote to her sister, “as I am to be deprived of your loved society… The kindness of strangers and friends excite[s] my warmest gratitude, but the love of my own is more precious than rubies. I do not love the South, but[,] as it is my home[,] must try to make the best of it.”[13]

Louisa Cutler McAllister at 64

Louisa’s husband was sensitive to her homesickness. Consequently, as Ward McAllister would later write, “this best of fathers sent his family North every summer, with one or two exceptions, to Newport, R.I.”[14] Summers on Aquidneck Island were a salve for the pain of great geographic distance.

“Our Terrestrial Paradise”[15]

Newport’s early tourists typically stayed in one of the city’s many boarding houses. Or they rented cottages on The Point or on Thames Street. Others, like McAllister’s extended family, preferred more space, opting to stay in farmhouses on the outskirts of Newport proper.[16]

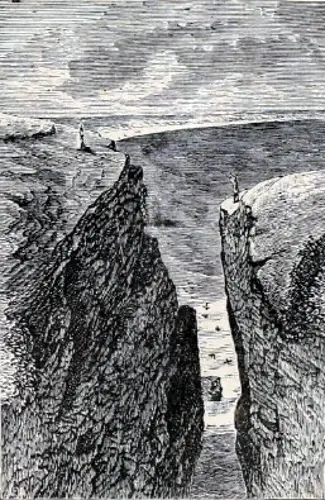

The Cutlers, McAllisters, Francises and Wards rented each summer from the Bailey family, not far from Third Beach in Middletown. When the weather cooperated, they enjoyed being outside. Ward McAllister—called “Wardy” in family letters— remembered flying kites and building crackling fires under the stars at Purgatory Chasm, a commanding rock formation overlooking Sachuest (Second) Beach.[17]

Purgatory Chasm

The rock formations of Paradise Valley were another favorite spot. As Ward’s uncle, Rev. Benjamin Clarke Cutler, wrote to a parishioner in Brooklyn:

In this retreat every thing is delightful. This morning I spent alone, rambling over the most glorious battlements of ocean scenery I ever saw. It is a place called Paradise, an immense pile of rocks, affording a view of the whole southern end of this fine island, and of a noble amphitheatre of sea and sky. Around are highly cultivated fields and farms, and near by, entirely sequestered, are groves of forest trees, affording a perfect shade, broken only to give a view of the neighboring ocean. The morning has been peerless; a cool, bracing air from the northwest, a bright sun and a clear sky, relived only by a few silvery clouds. I confess I have not for years been so elevated by natural scenery…[18]

From Paradise to Purgatory by William Trsot

Family letters — full of charming, funny stories of antics, outings, and visitors — capture the happy cacophony of the Bailey farmhouse. After long days exploring the Island’s natural beauty, everyone crowded inside and drifted to sleep on mattresses stuffed with corn husks.[19]

Town and Country

From the 1830s onward, Newport’s renown grew, but its atmosphere remained largely communal. Summer visitors of different backgrounds, regions and social classes sailed, swam and fished together. They might go into town to visit the Redwood Library or attend a theatrical performance. Or they’d dance at the immensely popular “hops” hosted at hotels. Construction of those hotels heralded the crescendo of Newport’s antebellum tourism scene.[20]

Young Julia Ward Howe, Ward McAllister’s first cousin and another visitor to the Bailey farm, captured the resort’s antebellum character, and her family’s place in it. The future activist, writer and “Battle Hymn of the Republic” lyricist observed, “Newport is quite full, visitors flocking from every direction… As for us, we eat, we drink, and sleep abundantly, ride and walk constantly, and are neither important, influential, witty nor wise.”[21]

Refuge from Cholera

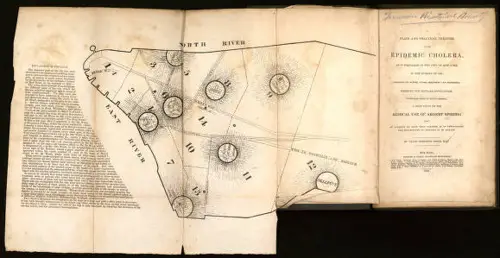

In the summer of 1832, family matriarch Sarah Cutler again “united the various branches of her family under one roof.” But this was no ordinary season in Newport.[22] Cholera had arrived in North America.

Carried on westbound ships, the horrific disease struck Canadian ports first and New York City shortly afterward. July and August 1832 saw roughly 2,500 cholera deaths in New York alone. The victims included Lt. Col. Samuel Ward, Jr., Sarah Cutler’s brother-in-law.[23] Those too poor, sick or otherwise unable to flee the crowded city fell victim to this vicious, stigmatizing and rapidly spreading infection.[24] “The accounts from New York keep us in a constant state of uneasiness,” Louisa McAllister wrote to her sister Eliza, who remained in the city, “and we long to gather our dear group at Bailey’s.[25]

Map of the New York City cholera epidemic

Newport was safer than New York, largely due to city officials’ quick enforcement of a strict embargo. No ships could come into port or leave. Even mail delivery paused, triggering increased anxiety at the Bailey farm. However, these precautionary measures proved effective. By the epidemic’s end, only nine reported cholera deaths had occurred in Newport. [26] Those lodging with the Baileys that summer were spared.

Ward McAllister’s New Age in Newport

Even years later, Newport remained central to Ward McAllister’s adult life. In 1852, he married Sarah Taintor Gibbons, whose father had loaned “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt money to buy his first ferryboat. The couple purchased a 50-acre parcel called Bayside Farm. Like the Bailey farm, it was located outside Newport proper and offered gorgeous views of the water. Prior to settling in New York in the late 1850s, the growing McAllister family lived at Bayside for nine months out of the year.

As the Civil War loomed, Newport’s social atmosphere shifted. Despite connections drawn by trade relationships and trans-regional marriages like Sarah Cutler’s and Louisa McAllister’s, southern newspapers urged their readers to shun northern resorts to demonstrate Confederate patriotism.[27] The “Southern contingent” that had fundamentally shaped the early tenor of 19th-century Newport’s tourism industry was quickly outnumbered by the northern elite.[28]

Watching a regatta from Castle Hill

Meanwhile, Newport’s reputation grew. So did the crowds. Fashion drove the center of Newport’s social life into the city limits, first to grand hotels like the Ocean House and, later, to subscription-based entertainment spaces like the Newport Casino and private homes.

Newport Cliff Walk ,1885

The “galaxy of most elaborate country houses” that later came to dominate proud Bellevue Avenue and Ocean Drive were “walled in” from prying eyes and parvenus “with an almost feudal aggressiveness.” [29] After the Civil War, as historian Rockwell Stenstrud writes, “Newport [became] unrecognizable to anyone who had been away for a period of time.”[30]

Adapting to the Gilded Age

McAllister, more savvy than often credited, remembered the old days. Witnessing Newport’s evolution had primed him to marry the Island’s antebellum charm with the “cutthroat culture” that permeated Gilded Age resort life at his Newport farm.[31] He did it with picnics.

Ward McAllister, seated with guests at a picnic

Guests included New York’s most powerful families—Astors, Whitneys, Vanderbilts, Wetmores. They picnicked alongside diplomats, state and local political figures, and even artists. However, McAllister once commented, “do not for a moment imagine that all were indiscriminately asked to these little fêtes… if you were not of the inner circle… it look the combined efforts of all your friends’ backing and pushing to procure an invitation for you.”[32]

During McAllister’s exclusive summer picnics, Bayside Farm’s rustic white farmhouse and picturesque livestock in the pastures—no matter that they were rented specifically for the occasion— created a “romantic, out-of-town feeling” that seemed like a novelty.[33] Guests feasted on rich delicacies and enjoyed champagne, claret and madeira from McAllister’s meticulously-curated collection. Afterwards, there was dancing in the barn, where a brilliant chandelier hung from the rafters.

Ward McAllister’s picnic table

Between food, decorations, table settings, music and other essential elements for hosting 140 people, one of McAllister’s picnics cost roughly $27,700 in today’s money.[34] The price, as one newspaper editorialized, “makes a plain, hungry, pickle-and-sandwich picnicker… smile.”[35]

A pinnacle example of McAllister blending his early memories with higher social stakes came in 1882. He organized a luncheon for President Chester A. Arthur overlooking Paradise Rocks.[36] To the “commander-in-chief of the 400,” the “noble amphitheatre of sea and sky” that his family had once enjoyed was unquestionably fitting for the commander in chief.[37]

The Last Valley-Paradise Rocks by John LaFarge

Ward McAllister’s Newport Summers

No matter how radically Aquidneck Island changed, McAllister and his extended family could always “make a little visit to Bailey’s and see the dear group in imagination.”[38] The social arbiter’s authority in Gilded Age Newport gains richness when understood as the culmination of generational visits throughout the resort’s 19th-century history. On Aquidneck Island, he and his family created memories, with enduring influence, to last a lifetime.

Ward McAllister at an 1890 picnic

Footnotes and an image guide are in a separate post. Click here to see them.

Emily Parrow earned her M.A. in History from Liberty University in 2021 and wrote her thesis on Ward McAllister and nineteenth-century Newport, Rhode Island. She currently serves as Manager of Individual Giving at The Mount, Edith Wharton’s Home, in Lenox, MA. Emily’s thesis can be accessed here: https://digitalcommons.