At 6’6” tall, Long John Wentworth of Sandwich, N.H., was a mountain of a man with unquenchable thirsts for wealth, power, and alcohol.

He was born in March of 1815 into the historic New Hampshire Wentworth family. Dartmouth College nearly expelled him for his outspoken opinion, but he graduated in 1836. He then left Sandwich to join the tide of New Englanders heading west to Chicago to establish a city. There, he rose to become a legendary mayor, crusading against crime and corruption. He agitated against slavery at every turn and made himself a millionaire.

Long John Wentworth

As a boy, Wentworth’s future seemed to be in farming, his first love. He was not a natural scholar, and his father pushed him to get a high school diploma. He spent some time at Berwick Academy in Maine, as well as New Hampshire’s Meredith Academy. Wentworth finally graduated from New Hampton School.

Several times he considered dropping out to return to Sandwich, and farming. In the end, however, Wentworth found he enjoyed his education and happily went on to Dartmouth College. He was very nearly expelled just shortly before graduation. While he never spoke much about the event, his biographers conclude that as a senior he got entangled in a prank involving some underclassmen. The younger men, upset at the treatment of two of their friends by a tutor, had liberated a cannon from the armory. They then shot it off in front of the administration building, shattering windows.

The school responded by expelling one of the younger men behind the cannon incident. Wentworth was likely so outspoken in his criticisms that the faculty ordered him expelled just days before he was to receive his diploma.

Wentworth, an ardent Democrat, most likely held his nose and groveled for forgiveness from the Whig-dominated faculty. He scooped up his diploma and ran for the exits, nursing a grudge against the college for years to come.

Young Man in a Hurry

Fresh from school, Wentworth returned briefly to Sandwich. His father, Paul, a town leader and successful businessman, had influence. And the family tree was a stout one, with two colonial governors and a signer of the Articles of Confederation in its branches.

When future president Franklin Pierce, then serving as a U.S. Senator, visited Dartmouth, he had taken the young Wentworth aside following commencement to ask for his father’s political support.

Wentworth, with his family ties and relative wealth, could have undoubtedly prospered in New Hampshire. But he didn’t want to to fall in line behind the state’s huge Democratic political establishment. He was a young man in a hurry, Almost immediately after school, he made plans to leave for Chicago, then But it that held just a tiny outpost. But it held promise for men who wanted to go west and find their fortunes.

The Windy City

Wentworth left for Chicago with $100 saved up. He belonged to a wave of New Englanders who set their sights on making fortunes in Chicago real estate.

Travelling through upstate New York and on through Michigan, Wentworth toyed with the idea of stopping in Detroit. But he continued on because of a lack of opportunity, arriving in Chicago in 1837.

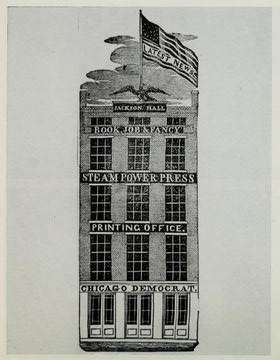

Armed with a letter of introduction from New Hampshire’s governor, Isaac Hill, Wentworth soon found his lifelong vocation: newspaper publishing. Just three year’s earlier, the Chicago Democrat had been founded as the first newspaper in Chicago. It struggled, and a group of new owners had taken over. Among them was Horatio Hill, the New Hampshire governor’s brother.

Hill hired Wentworth as editor of the paper, and promptly headed back East to raise funds. The financial panic of 1837 and depression that followed put the paper in even worse shape. Hill never apparently succeeded in raising any funds. Instead, Wentworth purchased the paper for $2,300 in 1840. He never acknowledged where he got the money, but it probably came from family.

Wentworth had a gift for newspapering. Sarcastic and blunt, he skewered his enemies with glee. He also used his connections to procure lucrative government printing contracts/ Printing work kept his income steady while he built a following for his newspaper.

By 1842, he had elbowed his way to the forefront of the local Democratic Party. He ran for Congress, and won, setting in motion a 25-year run during which he usually served in office, either as a Congressman or as mayor.

Long John Wentworth, Outsider

Arriving in Congress, Wentworth proved an effective advocate for his state. He even called on his fellow-New Hampshire native Daniel Webster for help in getting support for Chicago waterfront projects. But he also quickly found himself in the difficult position of outsider in his party, especially on the issue of slavery. While Wentworth’s Chicago constituents were vehemently abolitionist, the Democratic Party was increasingly aligning with slaveholders.

It quickly became apparent that Wentworth had no choice. He must become an outspoken abolitionist. This stance, however, put him at odds with the Illinois Democratic political machinery, much more aligned with the slavery-supporting Stephen Douglas.

In 1855 the Democrats turned Wentworth out. Though technically he did not stand for reelection, there is no doubt that his opponents had beaten him. Unfortunately for them, an abolitionist friend from New Hampshire replaced him . Wentworth had cemented his reputation as the angry outsider, and he soon fashioned it into a campaign platform, this time for mayor. And this time, he would run as a member of the newly formed Republican Party, breaking once and for all with his old Democratic friends.

So Annoying

Wentworth’s demeanor as much as his politics irritated his enemies. He drank a pint of whiskey a day (and more), and ate prolifically, At 6’6” tall and 300 pounds he was an imposing force. He freely castigated his enemies both in his newspaper and in his personal speeches.

A Boston newspaper described him as “A shabby elephantine individual” whose trousers looked “as if he had jumped too far into them and hadn’t time to go back.”

“We seldom come across a more soulless and heartless piece of political dishonesty than he who edits the Chicago Democrat,” wrote one Indiana newspaper of Wentworth.

And the Chicago Times, a paper launched and backed by Douglas, took note of his intentions to run for mayor in its pages. “The drunken revelries in which for several nights he has indulged in low brothels and in large saloons leave no doubt that he has commenced campaigning.”

In truth, Wentworth was no more prone to vice than much of the rest of Chicago, a point he drove home with his usual gusto as he settled scores with enemies and former Democratic friends once he was elected mayor.

His Lengthiness

In 1857, the young city of Chicago had a dilemma: what to do with shanty town known as “the Sands.” Sitting just north of the Chicago River, the real estate it sat on would be worth billions today The Sands was then a collection of illegal shanties, gambling dens and brothels, a cesspool of criminals from around the city.

Since Chicago establishment politicians were always well taken care of by its residents, nothing, it seemed, could be done about the Sands. As the new, no-nonsense mayor, Long John Wentworth decided to change that. He marched in to the Sands with a police force and started literally pulling down buildings and burning them, sending the crooks scurrying.

But it wasn’t just the illegal shanties he tackled. When politically-connected shopkeepers refused to stop cluttering the public streets with storage and outsized signs, Wentworth pulled all the junk into the streets put , He then put the businesses on notice that they only had a day to retrieve them.

His enemies called him the “Czar of Chicago” Other newspapers lampooned him as, “His Lengthiness, the Mayor.”

Wentworth enjoyed the notoriety, frequently traveling the streets at night with his police force, imposing law and order personally. As mayor he would cross the private fire companies, which were often little more than extortion rackets. He bought the city’s first fire engine, a steam pumper named “Long John.”

Too Cheap

His relations with other city leaders was not much friendlier. He pushed a tax increase to stop the rampant deficit spending that the city had engaged in. He opposed municipal water and, though the city hospital was completed on his watch, he thought it a waste of money. And when the city’s council authorized selling bonds to borrow money, which he didn’t like, he simply burned the bonds and stopped the sale.

After leaving office at the end of his first term, Long John decided he wanted back in office in 1860. Chicago was going to host the Republican National Convention, and he wanted to be the mayor of the host city when his fellow Illinois Republican Abraham Lincoln was nominated.

His second term was calmer than his first, but he returned to his tight-fisted ways — perhaps a bit too tight. At one point he reduced the city’s police department to just 75 men, prompting a spike in crime.

The state government, meanwhile, was growing fed up with his antics. It began to tamper with the city’s governance, changing the date of the local elections and establishing a police commission to run the city’s police department and end the harassment of the well-connected.

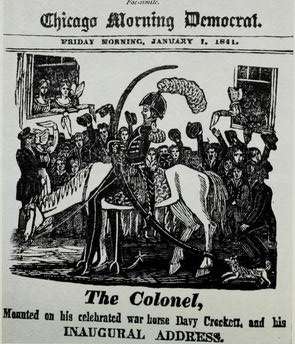

Long John responded by firing the entire police department before the commission could begin its work. And he made a desperate bid to hang on to office by declaring that there would be no 1861 elections, running a headline in his newspaper that said so.

Winding Down

But there were elections, and Long John, who had not formally sought reelection, was replaced. The final gasp of his career as an elected politician came in 1864. With the war ending, Wentworth wanted a hand in Reconstruction. He sought, and won, a seat in Congress. This stint in Washington ended with just one term, however, as he returned to Chicago once again to live out life as a gentleman farmer following his defeat for reelection. By that point, Wentworth had given away his struggling newspaper to the Chicago Tribune in return for assistance in settling a libel suit and an assumption of the newspaper’s debts.

Throughout Wentworth’s life, he never forgot his central purpose in coming to Chicago – to make his fortune in real estate. And he did just that.

In 1844 he had married Roxanna Marie Loomis, and they had five children together. Only one, daughter Roxanna, lived to adulthood. Roxanna, Long John’s wife, stayed for most of her life in her hometown of Troy, N.Y., where she tended to the Wentworth family while Long John shuttled between Washington and Chicago, with occasional stops in Troy.

She visited Chicago on numerous occasions, once for a prolonged stay, but her heart was in Troy. Using his father-in-law’s funds for backing, Wentworth accumulated substantial real estate holdings in Chicago and north of the city. It included hundreds of acres on the city’s South Side. Land where Comiskey Park is located was once his, as was the property that became the Union Stockyards.

Long John sold land and reinvested carefully throughout his life, and split his time between his farm and downtown office, where he remained active behind the scenes in Republican politics and gave frequent interviews and was the subject of many stories.

The Legend of Long John Wentworth

One story that is often told of Wentworth involved the financial panic of 1873. A bank run was under way, with crowds of customers gathered outside the bank. Walking along the street, Long John told everyone he met that he was carrying a pile of cash to put in the bank. “You fellows want money, stand back and give me a chance,” said John, waving a roll of bills. “I want to make a deposit of $20,000.” If the bank was sound enough for Long John, a millionaire, then depositors’ money must be safe, the crowd concluded. He would later tell people, with a wink, that the pile of bills was mostly a stack of confederate money that he kept as a curio, but it did the trick.

Throughout his life, John and his wife and daughter were frequent visitors to New Hampshire. They met with family and political leaders, including Franklin Pierce. His final trip to the state was to celebrate the unveiling of the statue of Daniel Webster at the Statehouse in Concord in 1886. He probably also talked with his brother Joseph about politics, though at that point it’s not clear how much the two had in common. John had turned Republican while Joseph would run for governor as a representative of the Prohibition Party. By that stage in his life, Long John had curtailed his drinking, but not by choice. It was a matter of health, which was slipping away from him.

Wentworth passed away in October 1888 and was buried beneath the granite headstone from Hallowell Granite Company in Maine. When he ordered it, he specified it should be the tallest in Chicago.

Thanks to Chicago Giant, A Biography of Long John Wentworth by Don. E. Fehrenbacher. This story updated in 2022.

7 comments

This along with all the other posts from the Historical Society are the best articles on Facebook

I agree!

I’m wondering if the town of Wentworth was named for his family.

[…] When he was about 13, the Southards moved to Chicago. […]

[…] in the evening, Susan was seated at the dining table with her mother and brother in their rural Carroll County farmhouse. The trial for breach of promise was set to begin the next day. Without warning, the […]

[…] John Wentworth, the son of Sandwich, N.H., who went on to serve as mayor of Chicago, recalled serving with Adams in Congress in 1843 just five years before Adams died. He wrote of the various nicknames that could be bestowed on him, from "old man eloquent" to "old man malignant." […]

[…] barely speak after suffering a stroke that partially paralyzed him at 78. Another congressman, John Wentworth, wrote, “It was understood in the galleries, as well as in the house, that the color of his head […]

Comments are closed.