The story of Maine statehood is also the story of a province and a people exploited by absentee owners and left defenseless in a time of war.

Most people view Maine statehood through the lens of the Missouri Compromise. To settle the national question of slavery, for a little while at least, Maine was admitted as a free state and Missouri as a slave state.

A fish weir in Maine

But, like Brexit two centuries later, Maine statehood resulted from an aggrieved but divided populace. It took longer than Brexit — 28 years. It also took six referendums and a war before the District of Maine escaped the rapacious grasp (to some) of Massachusetts.

But they did it, and Maine statehood began on March 15, 1820.

“The day was noticed, as far as we have heard from the various towns by every demonstration of joy and heart-felt congratulation, becoming the occasion,” reported the Eastern Argus on March 21, 1820.

Before Maine Statehood

Maine had once been an independent colony, but in 1691 the English Crown granted a charter giving Maine to Massachusetts.

Then for a century Maine languished as a colony of Massachusetts. In 1750, the population of Maine was pretty much the same as it had been 100 years earlier: about 10,000.

Fishing vessel

The reason? Violence. The French claimed nearly half of eastern Maine. They allied with the Wabanaki Confederacy and waged nearly a century of intermittent war against English settlers. Fighting between the English and the French and Indians started with King Philip’s War in 1675 and ended with the end of the French and Indian War in 1763.

From 1689 to 1713, there wasn’t a single English home north of Wells. And today, Maine has virtually no 17th-century houses in the state.

Only when the final Anglo-French war wound down did land-hungry Yankees start migrating en masse to Maine.

Land, Lots of Land

After the American Revolution, Maine’s population exploded. It rose from 56,321 in 1784 to 96,540 in 1790.

The land office couldn’t keep up with demand for land at $1 an acre up to 150 acres. Settlers could even claim 100 acres for free if they managed to clear 16 acres within four years.

Maine blueberry barren

Speculators, like William Bingham and Henry Knox, paid as little as 25 cents an acre for tracts of land the size of Rhode Island. When the American Revolution ended, Maine’s population had grown to 56,321. By 1820, 298,335 people lived in Maine.

Sardine Factory, by Leslie Landrigan

Maine began to prosper from fishing, lumber, shipbuilding and shipping, also known as the coasting or carrying trade.

Nineteenth-century records from Wiscasset show Maine’s “astonishing” dependence on lumber and shipping lumber, according to historian Ronald Banks. From January 1800 to January 1812, except two years for which figures are unavailable, 576 vessels left the port, wrote Banks. All 576 carried a main cargo of lumber, staves and other timber products. Only 20 carried something along with lumber. “There is no reason to believe Wiscasset was unique,” wrote Banks.

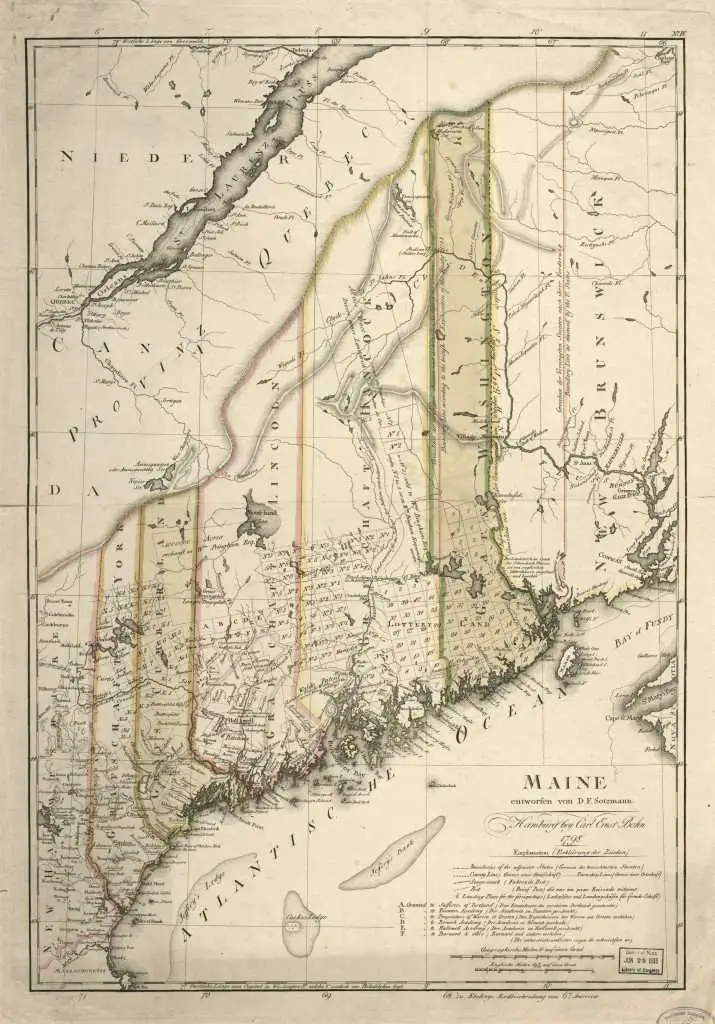

Maine in 1798

Blue Hill built so many ships that sawdust now makes up most of the first eight feet of mud in the inner harbor.

And yet the people who prospered most in Maine couldn’t catch up to those in Boston. The “better element” began to agitate for separation, arguing that Massachusetts overtaxed and underrepresented them. Boston, too, siphoned the profit from shipping and lumber through trade regulations.

From 1792 to 1807, Mainers took three votes on separating from Massachusetts. All three failed.

The Coasting Law

A big reason for Maine statehood to fail was a federal law governing interstate shipping. Congress gave Maine shippers a competitive advantage when it passed the Coasting Law of 1789.

Coasting vessels, typically schooners, hauled cargo up and down the coast, much like trucks today carry freight on the interstate. The 1789 law required coasting vessels to clear customs in every state except the state next door.

As part of Massachusetts, Maine coasters didn’t have to clear customs until they reached New Jersey, a considerable advantage to Mainers. If Maine were to separate, coasters would have to clear customs in Massachusetts–a costly and time-consuming prospect.

Separation

The War of 1812 gave Mainers a new reason to separate from Massachusetts. Many in Massachusetts opposed the war, and Gov. Caleb Strong refused to send Massachusetts militiamen into the fight. He left Maine on its own. The British captured Castine, Belfast, Eastport and sacked Bangor and Hampden.

Strong did lift one finger in defense of Maine. He appointed a wealthy capitalist from Bath, William King, major general of the Maine militia.

After the war, William King did not forget Massachusetts’ negligence. Nor did many Mainers.

King and many of the people of Maine were Republican-Democrats who supported Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Massachusetts, on the other hand, was dominated by Federalists. King believed the Federalists shut Republican-Democrats out of patronage and lucrative land, bank and insurance charters.

But the Federalists were on the way out, and the Republican-Democrats were on the rise. Maine’s Republican-Democrats thought statehood would bring lower taxes and freedom from self-important—and self-dealing–Federalists.

One of Maine’s many working waterfronts.

Many small farmers had grievances against the large landowners who charged them rent for land they thought they’d gotten free. Or they kicked the farmers off land they’d cleared and didn’t pay them for the improvements. The small fry in Maine’s interior thought Maine statehood would enable them to right those wrongs.

Besides, Maine was big enough to be its own state now, with a population of nearly 300,000.

Many Massachusetts Federalists wanted to free themselves from the Republican-Democrat Mainers who threatened to dominate them politically. They could solve that problem by cutting the province loose. So the Massachusetts Legislature on May 20, 1816, agreed to let Maine vote for separation.

Maine Statehood Fails in 1816

Maine held two votes in 1816 on statehood, and both times statehood lost. Coastal towns dependent on shipping voted overwhelmingly against it. No county cast more votes against separation than Hancock County. In heavily Federalist Blue Hill not one person from that town supported statehood. (The 1816 vote went 0-59 and 0-77.)

Stonington, Maine

William King realized the coastal towns voted against statehood because of the 1789 Coasting Law. Maine statehood would hurt Maine shipping and shipbuilding. Maine coasters couldn’t go all the way to New Jersey without clearing customs; they’d have to do it in Massachusetts.

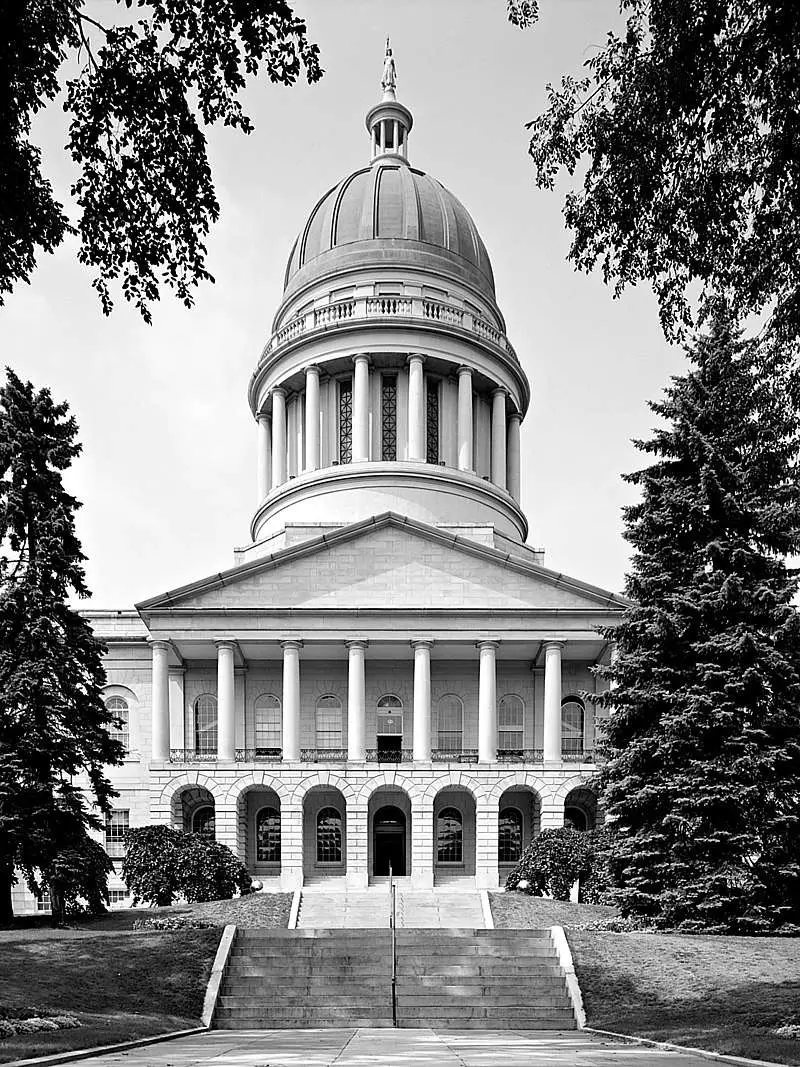

The Maine State Capitol in Augusta.

Fortunately for William King, he had a brother, Rufus, a U.S. senator from New York. Rufus King and other allies in the Senate managed to revise the coasting law.

And so on July 26, 1819, Maine took its sixth and final vote for statehood. A total of 17,091 voted for full Maine statehood versus 7,132 for remaining a province of Massachusetts.

Less than three months later, delegates from all over Maine traveled to Portland for the state constitutional convention. They took 18 days to draft a constitution, overwhelmingly approved by a popular vote in January 1820.

On March 15, 1820, William King became Maine’s first governor. Maine statehood was a reality.

With thanks to Ronald F. Banks, Separation of Maine from Massachusetts 1785-1820.

This story was updated in 2022.