Melvil Dewey had an obsession with the number 10. He slept 10 hours, wrote 10-page letters and created the Dewey Decimal System to organize libraries. He also had an obsession with women, as in kissing and hugging them. Which is why he’s described as having a “complex legacy.”

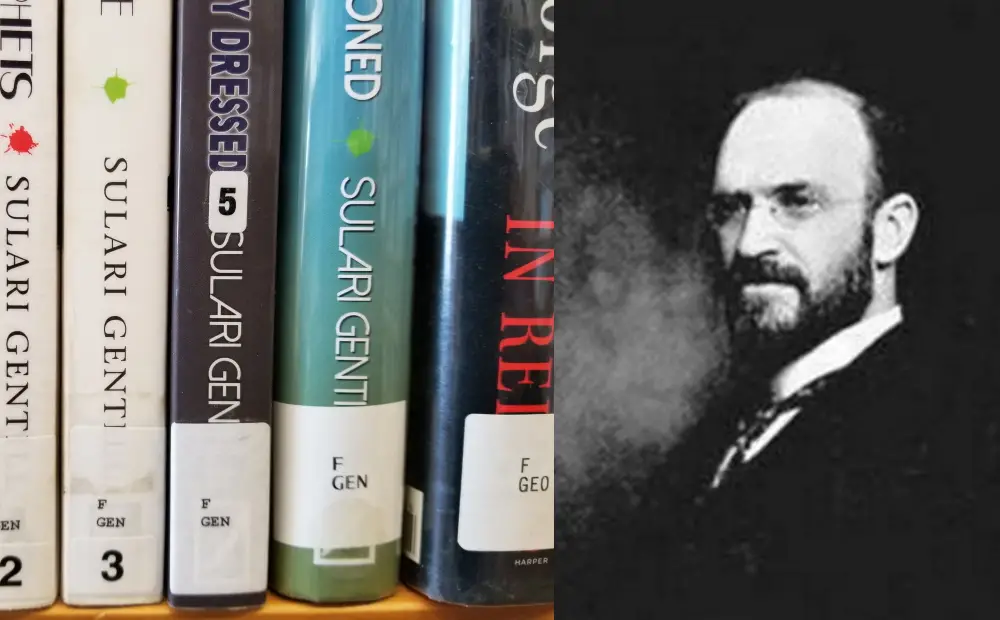

Melvil Dewey

Dewey had an enormous impact on the development of libraries in the second half of the 19th century. He founded Columbia University’s library school and the American Library Association, and he started the traveling library, the library for the blind and the interlibrary loan. He also helped organize the 1932 Olympics in Lake Placid, where he started a health resort. There his obsessions manifested themselves with $10 membership and a requirement that people turn out their lights at 10 p.m.

Another unpleasant Dewey trait showed up at Lake Placid: his bigotry. He only allowed white Christians into his resort.

Those biases were reflected within the Dewey Decimal System, which marginalized non-Eurocentric subjects.

Melvil Dewey

He was born in 1851 in Adams Centre in upstate New York, known as the Burned-Over District. Waves of reform and evangelism swept over it from 1800 to 1850. The district gave rise to Mormonism, Millerism, the Shakers, the Oneida Colony, abolitionists, suffragists, temperance, educational reformers and Melvil Dewey.

His parents, Joel and Eliza Dewey, made and sold boots and shoes from their little shop. Known as the hardest working people in town, they did not show much affection. That may explain their son’s predilection for unwanted hugging and kissing of women.

As a boy, he had a mania for system and classification. According to an aunt, he liked to arrange his mother’s pantry. He earned nickels and pennies for doing chores and then walked 10 miles to buy an unabridged dictionary with his savings.

His obsession with the number 10 began in high school when he discovered the metric system. He also realized his birthday, December 10, 1851, occurred exactly 52 years after the French National Assembly adopted the platinum meter bar as a standard unit of measurement. The meter measures one ten-millionth of the shortest distance from the North Pole to the equator passing through Paris.

On Jan. 29, 1868 16-year-old Melville Dewey was attending class at the Hungerford Collegiate Institute, a college prep school. A fire broke out in the building, and Dewey carried as many books out as he could. The fire got worse, so he watched from outside in the cold. Exposure and smoke inhalation resulted in a bad cough that left him bedridden for months. His doctor didn’t think he’d live. That near-death experience left him obsessed with something else: efficiency, because life is short.

Amherst College

After high school he taught for a while, went to Alfred College for a semester and then transferred to Amherst College.

In his junior year at Amherst he got a job at the library, then in Morgan Hall. He fretted over the unsystematic way the library shelved books. Back then, libraries had their own systems, but they had to re-catalogue and re-index books when they acquired new ones.

Main quad at Amherst College

Dewey had an “aha” moment when he came up with the answer: a system using letters and decimals to organize books according to their contents. He suggested it to the Amherst Library Committee, which liked the idea. Not only did the committee let him implement it, it named him assistant librarian.

He graduated in 1874, but continued to work at the library. In 1876, he published A Classification and Subject Index for Cataloging and Arranging the Books and Pamphlets of a Library. Today, more than 200,000 libraries in 135 countries use it, according to one estimate.

Another of his ideas didn’t go over so well: spelling reform. He changed the spelling of his name from Melville to Melvil to eliminate those inefficient and unnecessary letters at the end of his name. He often signed his last name Dui.

In 1876, he left Amherst for Boston—regretfully, according to his efficient spelling.

“Sum day, dear Amherst, may it be my happy lot tu pruv how great iz the love I bear yu. Proud, always, everwher to be counted among yur sonz, I am Very truly, Melvil Dui.”

Boston

Two years after moving to Boston he married Annie Godfrey, the former librarian of Wellesley College. They had one son, Godfrey.

In Boston he started a company that made and sold library supplies, including the hanging vertical file, which he invented..

From Boston, now “Melvil” organized a librarian convention at the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia, which then led to the American Library Association (ALA). He also helped found the American Library Journal.

New York

Dewey and his family moved in 1883 to New York, where he got a job as librarian at Columbia University. There he founded the school of library economy. He encouraged women to apply, probably so he could get at them more easily. He admitted 17 women and three men. Applicants had to submit photos so Dewey could gauge their attractiveness. Dewey often commented “You cannot polish a pumpkin.”

Low Library at Columbia University

Columbia officials didn’t like having ladies at the college and decided to close the library school. But in 1888, Dewey left for Albany, where he got a job as state librarian. He also took his library sciences school with him, reestablishing it as the New York State Library School. (It returned to Columbia in 1926.)

Over the next 20 years, Dewey expanded and modernized the state library. Gov. Teddy Roosevelt called it “an inspiration to intellectual life throughout the state.” As state librarian until 1906, he created the first library for the blind, the first traveling library, the first interlibrary loan program and the first children’s library.

Olympics

In 1895, while serving as state librarian, he founded the Lake Placid Club, a health resort. There he could indulge all his whims, his obsessions and his bigotry. He banned Jews, blacks and other religious and ethnic groups. Dewey also continued his unwelcome hugging, kissing and touching of female subordinates.

And at Lake Placid, he could spell the way he wanted to. One 1927 menu listed “hadok, poted beef with noodls, parsli or masht potato, butr, steamd rys, letis, and ys cream.”

A promoter of winter sports, he also helped organize the 1932 Olympics at Lake Placid.

WPA poster for the 1932 Olympics

That Complex Legacy

He did have friends, who sometimes got tired of defending him against persistent complaints about his behavior. In 1924, Tessa Kelso, former head of the Los Angeles Public Library, wrote in a letter, “For many years women librarians have been the special prey of Mr. Dewey in a series of outrages upon decency.”

In 1906, he went on a trip to Alaska sponsored by the American Library Association. He hit on four prominent librarians during the trip. Unlike women he’d hugged and kissed in the past, they spoke up. Dewey had to quit as state librarian.

At least one woman welcomed his advances. In 1924, two years after his first wife died, he married Emily McKay Beal.

In 1930, at the age of 78, he had to pay his former secretary at the Lake Placid Club more than $2000 in a sexual harassment settlement.

System of Bigotry

It wasn’t just his personal behavior that inspired criticism. His Dewey Decimal System marginalized non-Christian religions and the works of people of color. It also classified lesbian and gay subjects under “Abnormal Psychology,” “Perversion,” “Derangement” and “Medical Conditions.”

New York State Library

Dorothy Porter, for 40 years librarian at Howard University, challenged the Dewey Decimal Classification. “Now in [that] system, they had one number—326—that meant slavery, and they had one other number—325, as I recall it—that meant colonization,” she said in her oral history.

Porter said that in white libraries “every book, whether it was a book of poems by James Weldon Johnson, who everyone knew was a black poet, went under 325. And that was stupid to me.”

Porter developed a new system of classification. Ironically, she was the first African American to graduate from Columbia’s school of library science.

Melvil Dewey died December 26, 1931, of a stroke at Lake Placid.

In 2019, the American Library Association voted to take Dewey’s name off of its highest honor, the Melvil Dewey medal. ALA members voted to rename it the ALA Medal of Excellence.

With thanks to Joshua Kendall Melvil Dewey, Compulsive Innovator in American Libraries March 24, 2014; William Weigand, Irrepressible Reformer: A Biography of Melvil Dewey and to Mass Moments, Dewey Proposes Library Classification System.

Images: Amherst College By David Emmerman – PicasaWeb, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10411732.

This story last updated in 2022.