Amos Whitney came from American industrial royalty. His father was a locksmith, his grandfather a blacksmith and another wing of the family included Eli Whitney of cotton gin fame. His friend Francis Pratt didn’t have his industrial pedigree, but showed an aptitude for mechanical things as a small boy.

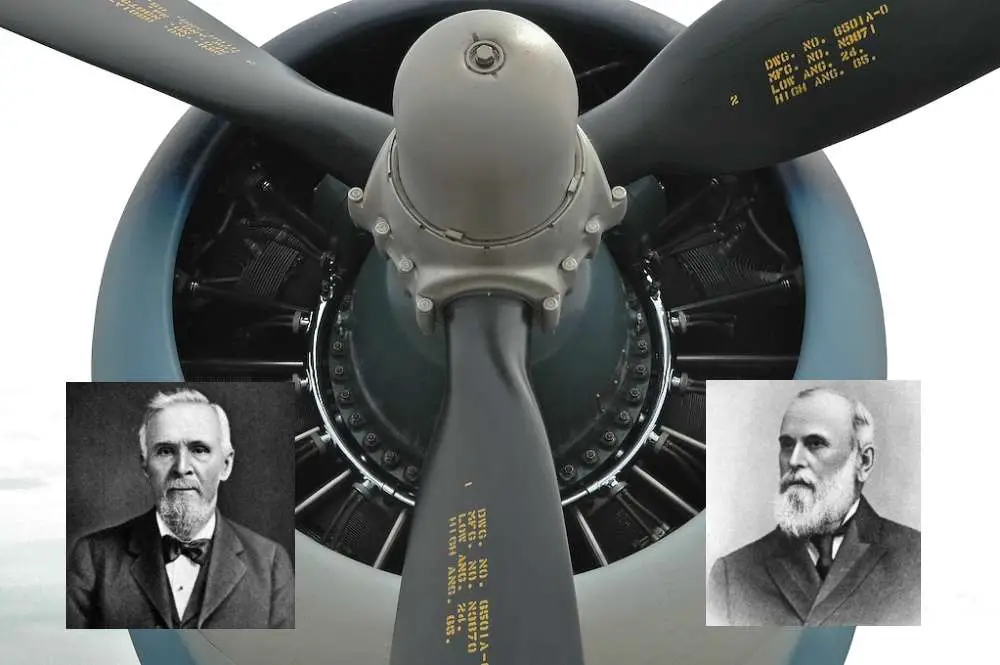

Amos Whitney (l) and Francis Pratt (r)

Together they would build an aerospace company that straddled the globe.

Amos Whitney and Francis Pratt

Born in Biddeford, Maine, in 1832, Whitney apprenticed at age 13 to the Essex Machine Company in Lawrence, Mass., which built locomotives, steam engines and textile machinery.

By 1850 both Amos and his father had moved to Hartford, Conn., where they worked for the Colt Manufacturing Company.

Francis Pratt was five years older. Originally from Woodstock, Vt., he and his family moved to Lowell, Mass.. when he was eight. He apprenticed to Lowell machinist Warren Aldrich. His career then took him to New Jersey and back to Hartford, where he joined Colt in 1852 for two years.

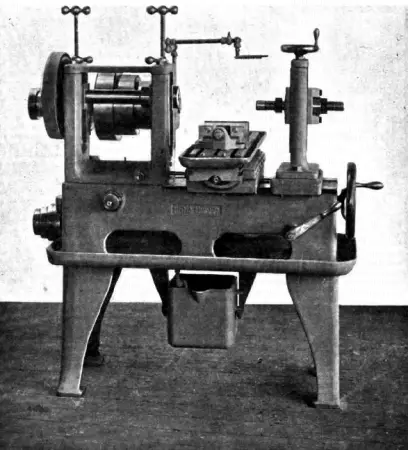

These two young men rode the wave of industrialization to the same factory and formed a friendship. Pratt would leave after two years to become superintendent of the Phoenix Iron Works, headquartered in Phoenixville, Pa. Pratt had invented something called the Lincoln miller – a milling machine that sped up the process of machining metals. It pushed the industry forward by leaps and bounds.

A Lincoln miller built by Pratt & Whitney

At Phoenix, Pratt served as a contractor to Colt. And when he proposed that Whitney, then making $8 a day at Colt, join him at Phoenix for $2 a day, one can imagine he needed a bit of salesmanship.

No Standards

But the two did reunite under the Phoenix roof with Pratt as foreman and Whitney as machinist. It’s difficult to imagine today the standards that these two machinists operated under. There was virtually no standardization of parts in metal working. Bolt threads and widths varied from one plant to the next. The industry couldn’t even agree on a standard for measuring how long a foot was, or an inch.

Pratt and Whitney became leaders in the push to standardize parts and measurements, and they made great strides funding a device that would create a comparator for parts so they could be universally standardized.

But before those great successes, the two had their hands full at Phoenix, deluged with contract work from Colt. The firearms company was arming the North in the Civil War.

Nevertheless, in 1860, the two men formed a small joint venture in a single room at the Phoenix Plant. There they built a thread winder for the Willimantic Linen Company. Two years later, they brought in a financial partner. All three put up $1,200 to move more aggressively into supplying the arms manufacturing industry.

Pratt & Whitney Rise and Survival

In four years the company’s assets grew from that initial $3,600 to $75,000. In 1869 the Pratt & Whitney Company was formed with $350,000 in assets. By 1893 when it was again reorganized, it was worth $3 million.

Shown is a Pratt & Whitney R-2800-8 engine in a Goodyear FG-1 Corsair.

The company thrived by advancing standardization and by shrewd business practices. When the 1873 panic demolished most of the American economy, Pratt & Whitney survived because it had stretched its wings and gone abroad to Europe in search of contracts.

The company’s catalog filled hundreds of pages with parts, equipment and finished products ranging from sewing machines and guns to typewriters and bicycles. Mark Twain was an investor in one of the company’s typewriters.

Pratt travelled to Europe frequently and found outdated equipment still operating in the factories of Prussia and Germany. The $2 million worth of orders for machining equipment Pratt procured kept the company from collapse.

Whitney, meanwhile, was a workaholic and a fanatic for precision. He rarely took vacations (though he did travel for business). Whit, as the employees called him, would walk the floor of his facilities chatting with the workers and carrying a rasp, always on the lookout for a rough edge that needed smoothing.

Wasp Rotary Engine

Pratt & Whitney factory in East Hartford

Reorganized and merged many times over, the company would, in 1925, launch the Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Company. It built the Wasp rotary engine, the cornerstone of the company’s aircraft engine line that survives to this day. Many old Wasps are still flying.

By then, Pratt was long gone. He had died in 1902. Whitney had moved on. He retired from Pratt & Whitney in 1901 and moved back to Maine. But he remained active as treasurer in his son’s company and as an officer in the Gray Telephone Pay Station Company until he died in 1920.

William Gray, while working at Pratt & Whitney, had invented the first coin-operated telephone. Amos helped him commercialize the product.

This story was updated in 2023. Images: Pratt & Whitney factory by By DanielPenfield – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21841333. Wasp engine by By en:User:Cogset – English Wikipedia (former file name : Image:F4u-2005COCwaspFG1.jpg), CC BY 1.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1621042

7 comments

Great article! You might want to change your sub-head, which mixes up their names

Thank you!

Yankee ingenuity at its finest. Great article.

Haley Sears

My son went to college in Biddeford, Maine, a beautiful town.

military aircraft also.

Awesome smart men

Comments are closed.