Prohibition in Rhode Island, always New England’s naughtiest state, failed not once, not twice, but three times. Each time booze was banned, Rhode Islanders made it clear they couldn’t abide Prohibition.

Rhode Island temperance advocates pushed through Prohibition twice before the Eighteenth Amendment forced the entire country to go dry in 1920. During the first two tries, two ardent teetotalers’ lives were threatened. One was murdered.

The third attempt at Prohibition in Rhode Island went even more spectacularly wrong. The Coast Guard started gun battles in Narragansett Bay, ordinary Joes turned into criminals and criminals got organized — and rich. Ray Patriarca, who would ruthlessly control the New England mob from Providence, got his start as a bootlegger.

Even Al Capone was said to have had an illegal drink in Rhode Island.

Prohibition in Rhode Island

The urge to ban booze began inside Protestant churches. Temperance advocates saw alcohol as the cause of urban crime, poverty and violence. They also thought it unhealthy and expensive. They believed prohibition would lower society’s costs for poorhouses and jails, and it would improve everyone’s health and welfare. Immigrants, many of them Catholic, saw temperance as an attack on them. They weren’t wrong.

Maine in 1851 first tried Prohibition in the United States. Other states followed, but people called alcohol bans elsewhere the “Maine Law.” Catholic immigrants in Maine thought it was aimed at them. They rioted in Portland against the city’s teetotaling mayor, Neal Dow. Maine then repealed the Maine Law after five years.

Rhode Island first tried it in 1852. The experiment lasted 11 years.

Political cartoon depicting the Woman’s Holy War against booze

That first attempt at Prohibition in Rhode Island had many detractors – including whoever murdered Burrill Arnold on May 27, 1859, in West Warwick. His friends thought his temperance activities led to his assassination, the local newspaper reported.

Nor did returning Civil War soldiers have any use for Rhode Island’s dry regime, Russell DeSimone speculated in Small State, Big History. Rhode Island repealed Prohibition in 1863, and DeSimone suggested battle-hardened veterans forced the issue.

Second Time Around

Rhode Island did it again in 1886 with a constitutional amendment. The Providence Journal predicted failure. The newspaper was correct.

The General Assembly left enforcement up to the cities and towns, and most cities and towns did little to discourage drinking. East Greenwich, however, waged a determined battle against the rum traffic. That led to the East Greenwich Outrage – attempts on the lives of two ardent prohibitionists. One found arsenic his well on the same day a small explosion went off in the house of the other.

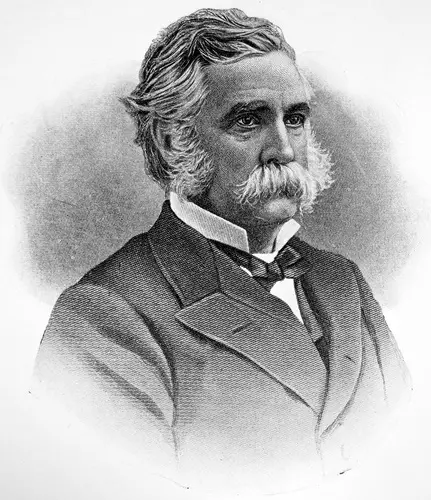

Rhode Island Gov. John Davis missed that licensing revenue

Gov. John Davis opposed Prohibition in Rhode Island as well. The state lost $100,000 in licensing revenue and ran a deficit of $114,000, he said. “This is not a cheerful showing from a financial point of view,” he said, according to the local newspaper.

Three years after Rhode islanders approved Prohibition, they repealed it. On June 20, 1889, 75 percent of voters (all adult males) voted against the law.

Third Time No Charm

Rhode Island learned its lesson. When it came time for the states to ratify the Eighteenth Amendment, Rhode Island refused to go along. Thirty-six other states did, however, and Prohibition took effect for a third time on Jan. 17, 1920.

No town in Rhode Island could claim it didn’t have illicit liquor-related activities. In Providence, bootleggers moved into the Biltmore Hotel, newly built with multiple bars. They set up headquarters, and hotel staff made a little extra cash by filling guests’ flasks with illegal booze from a speakeasy nearby.

A few blocks away, the folks at Camille’s Roman Garden made hooch in the basement and served it upstairs in coffee cups to patrons seated in curtained alcoves.

General Stanton House, once a speakeasy

Illegal hooch flowed freely in Kent County: in West Warwick, Old Warwick, Warwick Neck, Arctic, Apponaug and East Greenwich.

In Charlestown, the General Stanton Inn had to add a room to handle to overflow of bootleggers and rum runners. Guests included Al Capone and Tallulah Bankhead.

The Bootlegging Life

During the Depression, Prohibition offered people a way to make a living. A former bootlegger who called himself “Ron Deaver” described how it happened in an interview with Old Rhode Island magazine in 1991 when he was 97 years old. Small State Big History picked it up.

Hell, we didn’t have any choice. There weren’t no jobs, and if you did find a place that was hiring, there would be 500 people lined up in front of you . . . all wanting the same job. It was the time of the Depression. I lived with my sister and her husband for a while and I was waiting tables in a restaurant. I made $9.36 the first week. This was during Prohibition, and it didn’t take me long to figure that people were more interested in drinking than eating. I made a connection with old man Giles, and he would let me have five or six half pints on credit. I would then go to work, put one of the bottles in my pocket, and as I waited tables, I would drop a hint that I could get them some liquor if they wanted. I made 35 cents on every half pint at first, but it wasn’t long before I got the price up.

Nearly everybody broke the law. Deaver said he delivered three or four cases of scotch to a congressman when he visited his home in Newport. The politician had voted for Prohibition.

Ships of the Line

At first, said Deaver, most of the liquor came in by speedboat from New York or Canada, but after a while it came in by the shipload.

The ships would anchor right outside the seven mile limit, and smaller boats would go out and take on loads. Sometimes, if you couldn’t find the brand you needed, you would go shopping out there. You would pull up next to one of the ships, ask them what brands they had and how much it was. Some of the ships would actually fly a pennant showing what they had on board. Everyone’s favorite was the “Johnny” ship. It had a large pennant, must have been 20 or 25 feet long flying from the bridge, with the words “Johnny Walker…Imported” on it.

Got to where there was so many ships out there it looked like we were being invaded.

Prohibition agents examining barrels of liquor seized from a rumrunner. Image courtesy Library of Congress.

Prohibition also made mob kingpins rich. Carl Rettich ran a bootlegging operation out of his crime castle in Warwick. Police believed he killed his rival, Danny Walsh, who also got rich off bootlegging. Walsh’s girlfriend talked too freely, and police believed Rettich disposed of her, too. She may have been the first person to wear cement overshoes.

Raids and Gun Battles

The feds tried to stem the flow of hooch. They raided Twin Oaks in 1933, five years into Bill and Eva DeAngelus’ operation as a speakeasy in their modest Cranston farmhouse. He had been making moonshine in the basement, while she made meatball sandwiches upstairs.

Federal agents destroying barrels of booze

They also raided Rettich’s crime castle. They didn’t find the bodies they sought, but they eventually accumulated evidence implicating Rettich in the disappearance of Danny Walsh, a dozen Massachusetts bank robberies and four murders. Rettich went to prison, and the 11 local police officers he bribed to look the other way left the force.

Carl Rettich’s house, where Danny Walsh may have been killed. Photo courtesy Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.

The Coast Guard battled rumrunners in Narragansett Bay with machine guns and cannon, sometimes within sight of spectators on shore.

An incident in Narragansett Bay on Dec. 29, 1929, helped put an end to Prohibition. Just after 2:00 a.m., a zealous Coast Guard rum chaser, CG-290, went after the Black Duck, a speedboat carrying illegal liquor. Boatswain Alexander Cornell opened fire on the Black Duck, killing three men on board and wounding the fourth.

Many people sided with the Black Duck. The trigger-happy boatswain received a letter addressed to “Mr. Cornell, the Hun.” It warned him not to come ashore because, “Death is waiting for you and your crew.” A few days after the shootings, protesters held a meeting in Boston. The meeting chairman claimed 1,100 people had perished in the so-called “Rum War.”

On December 5, 1933, Prohibition ended with the ratification of the 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Rhode Island would never try that again.

Images: General Stanton Inn By JERRYE & ROY KLOTZ, M.D. – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=49470434