Richard Potter, the son of a former slave, won fame and fortune with a bag of magic tricks and a voice that spoke from ladies’ purses and gentlemen’s pockets.

Born during the last year of the American Revolution, he trained as a magician and ventriloquist. He traveled the world entertaining enthusiastic audiences and settled on an estate in New Hampshire. The traces of Richard Potter’s life can still be found in an Andover, N.H., train station, in the pages of the novel Peyton Place and in the magical arts.

John Hodgson, who wrote a biography of Potter, called him the first black celebrity, the first American ventriloquist and the most famous performer in the United States.

Successful, wealthy, well-liked—all those words describe Richard Potter. So does another: tragedy.

Richard Potter

He was born in Hopkinton, Mass., in 1783 to a black mother and a white father. His mother, Dinah, worked as a servant in the estate of Sir Charles Frankland, a descendant of Oliver Cromwell and collector of the Port of Boston. Frankland had fallen in love with Agnes Surriage, a beautiful tavern wench in Marblehead, Mass. He paid for her education and kept her as his mistress. That did not sit well with Boston society, and so Frankland bought land in the distant town of Hopkinton. There he built a showplace mansion.

By the time of Richard’s birth, Sir Charles had died and the estate started to decay. Some people thought Richard’s father was Sir Charles’s son. But it was George Stimson, a randy revolutionary war veteran. Stimson, according to church records, had “made attempts on the chastity of several women.”

One of those women was Dinah. Slavers had captured her on the Guinea coast and sold her on a Boston pier. But in 1769, a slave in Cambridge, Mass., brought suit against his master. He won his freedom and payment for his work. Soon after, Frankland’s estate freed Dinah and her children and paid them for their work.

Youth

Richard Potter spent the first 10 years of his life between the Hopkinton estate and Frankland’s townhouse in Boston. He learned to read at the Hopkinton District School. At the age of 10 he went into service for two years with Isaac Surriage, Agnes’ brother. Then he engaged himself to a Boston merchant. At around age 16, he took a trip to Europe with the merchant’s son-in-law. There Richard, always nimble and quick, picked up skills as a ropedancer and tightrope walker.

A ropedancer

From there the outlines of his life get muddy. He went to work at the New Hampshire Hotel in Portsmouth. An Italian tightrope walker named Signior Manfredi brought his show to that city, and Richard Potter may have joined him then as a minor performer in the troupe.

Somehow, probably in Boston, he met a Scottish magician and ventriloquist named John Rannie. By 1804, he had a job as Rannie’s stage assistant.

19th-century Portsmouth

John Rannie

Rannie swallowed razors, turned a bottle of water into Madeira wine, smashed watches then restored them. He made voices talk from under furniture and gentlemen’s pockets. In one gruesome trick, he cut off a chicken’s head and reattached it. It then ran off unharmed. One of Richard’s jobs was to find two chickens with identical markings.

John Rannie had spent a month in an Inverness jail for his role in a food riot (called “meal mobbing”). Authorities then banished him from Scotland, and so he went on an extended tour of the United States with Richard Potter at his side. They performed from Maine to the West Indies to New Orleans.

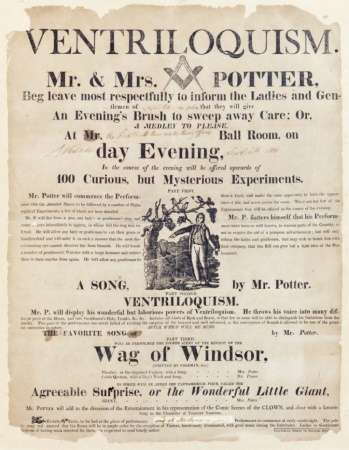

The Exchange Coffee House

Rannie retired in Boston, then returned to Europe in 1811. Richard Potter took to the stage on his own with many of Rannie’s tricks, including ventriloquism. He often played Boston at such venues as the Columbian Museum, the Exchange Coffee House, Concert Hall and Julien Hall.

Richard Potter’s Act

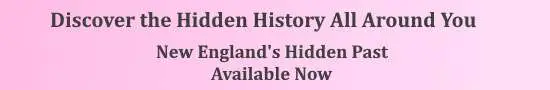

“He intends to give an evening’s brush to sweep away dull cares,” proclaimed his handbills. He called himself “Mr. Potter, the Ventriloquist and Comedian, from Saddler’s Wells (London).” Many Bostonians considered the theatre disreputable, but Sadler’s Wells was a respectable house patronized by fashionable Londoners. Richard’s nod to the English theater told people he put on a sophisticated, European-style show.

Sadler’s Wells

In 1808, he married Sally Harris, described as “beautiful and graceful.” They lived on Beacon Hill, a tight African-American community with a meeting house, a school and Underground Railroad stations. In 1811 Potter joined Boston’s African Lodge No. 459, the first black Masonic lodge in America. Another well-known African-American belonged to it: David Walker, who advocated the violent overthrow of slavery in his incendiary pamphlet, An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World.

But there was nothing incendiary about Richard Potter. One of the few black performers of his day, he presented himself as well-mannered, modest, charming. He dressed fastidiously in a neat frock coat, cravat and waistcoat with lapels, along with a flowing blue robe adorned with Masonic symbols.

“While other magicians catered to the enlightened and up-to-date, Potter presented a family entertainment,” wrote Paul A. Johnson. He played to children, who he admitted for half price. Those children included Oliver Wendell Holmes and George Hill, who became a comedic actor known as Yankee Hill. Both fondly recalled Potter’s shows later in life.

George Hill

The Magic

Richard Potter promised “100 curious but mysterious experiments” in the broadsheet advertising his show.

He did card tricks, made coins pass through wine glasses, broke eggs into a hat and then turned them into pancakes. One of his most popular acts was the enchanted egg, which magically traveled from one hat to another and then to his shoulder.

Map mmarked with the Columbian Museum, one of Potter’s Boston venues.

He threw his voice into a teapot, mimicked birds and animals, made a child speak from a ladies purse. So strange and startling were his effects they sometimes caused people to faint.

He also acted out scenes from plays like the Wag of Windsor with his wife. They sang comic songs like “Giles Scroggins’ Ghost” and “Barney Leave the Girls Alone.” Sally sang “The Nosegay Girl.”

Playing with Fire

For seven years he played mostly before audiences in New England and the Hudson Valley. He earned as much as $250 a day, worth about $3,000 in today’s money.

By 1819, his act evolved to include knife throwing and playing with fire. He appeared in Providence as the “Anti-Combustible Man Salamander,” bending a red-hot iron bar with his bare feet and drawing it over his tongue. He walked on hot coals in his bare feet, plunged his hand into molten lead and climbed into an oven where meat was roasting—always emerging unscathed.

His reputation grew with his fame, and it was said he could crawl through a solid log. Some believed he and Sally had performed the Hindu Rope Trick—throwing a rope up into the open air, then climbing it and disappearing.

Advertisement for a reproduction of the trick by stage magician Howard Thurston.

In 1820, he embarked on a four-year grand tour that took his show to the South, the West, Europe and the Caribbean.

Discrimination

Surely he knew of the dangers of travel for a black man. Sometimes he wore a turban when performing, suggesting he came from the West Indies or even India.

Once, in Mobile, Ala., Potter got kicked out of a hotel because of his race. He moved to another hotel, played for 12 nights and took in $4,800 in silver, which he carried in a nail cask. Upon his departure he learned highway robbers planned to waylay him. So Richard Potter let it be known he was going one way the next day, then left that night in the opposite direction.

Word of a planned slave uprising preceded his arrival on the eastern seaboard. Dozens of plotters, including Denmark Vesey, were arrested and executed. Richard Potter decided to bypass Savannah, Ga., and Charleston, S.C., lucrative venues but dangerous for a free black man.

He faced discrimination in the North as well.

In a New Haven hotel, the proprietor wouldn’t let him into the dining room because of his skin color. But when the host started to carve the roast pig for dinner, Potter threw his voice so the pig seemed to squeal.

New Hampshire

In 1814, he bought 175 acres in Andover, N.H., a small town on Ragged Mountain. He may have chosen Andover because of his friendship with Benjamin Thompson, a tavern owner who traveled with him as his assistant. The town of 1,800 had only 17 black residents in 1830, but he won the respect and trust of his neighbors. One described him as “public spirited, honorable in business, prompt to pay, a kind neighbor and trusted friend.”

Ragged Mountain

Richard Potter built a large, ornate house on his property and hired laborers to farm it. He only lived there intermittently, until about 1823. The Potters entertained frequently. One night, a guest complained about the alcohol served at dinner. So he broke the bottle and presto! He produced a baby chick—then made it speak.

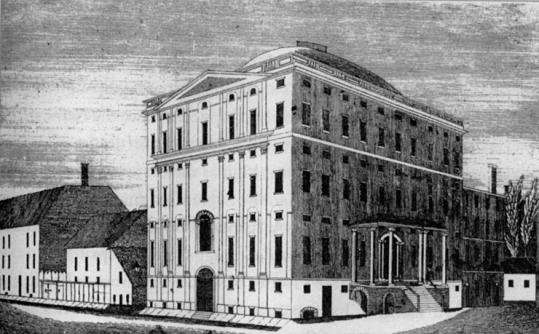

The house no longer stands, but the neighborhood is still known as Potter Place. Richard and Sally Potter are buried on his former property, and the Andover Historical Society planted a garden where his house once stood.

Family Trouble

At some point, Sally stopped performing with her husband. She begin to drink and spend extravagantly. Richard Potter returned from the road in 1825 to encounter debts and lawsuits caused by his wife. He almost lost his house. The sheriff did seize his livestock, furniture and hay and oats. Potter published a notice saying that only he could buy anything on his account.

Tragedy, however, had already followed Richard Potter. He and Sally had two sons and a daughter. Their son Henry died at age seven in a wagon accident.

Daughter Jeanette was described by a local historian as “a half-idiot, given to uncontrollable lewdness.” She died in 1831 at age 16.

Their son Richard, Jr., took after his mother, turning to drink and squandering money.

Richard, Sr., died on Sept. 20, 1835 at 52, leaving an estate worth $6,000. Richard, Jr., took over the Andover farm and cared for his mother. Sally died a year later, on Oct. 24, 1836. Richard, Jr., ran up debts and auctioned off the farm in 1837. He had his father’s magic kit and knew his act, so he went on the road as “Little Potter.” He failed and returned to Andover only to face lawsuits for unpaid bills. Then he mortgaged the magic kit. When it was seized for nonpayment, Richard, Jr., stole it back and disappeared from the historic record.

Potter Place railroad station

Remembering Richard Potter

He may have been forgotten elsewhere, but New Hampshire remembers Richard Potter. The village in Andover where he had his estate is still known as Potter Place, and a train station bears the name.

In 1965, the Manchester chapter of the International Brotherhood of Magicians officially name themselves the “Black Richard Ring.”

New Hampshire writer Grace Metalious modeled a character after Richard Potter in her novel Peyton Place: Samuel Peyton was a wealthy black man who built a castle on a hill in a small New Hampshire town.

For years, a magician named Robert Olson has re-enacted Richard Potter’s magic show. See it here.

Much of Richard Potter’s early life was an enigma. In 2018, John Hodgson cleared up a lot of the mystery in his 2018 book, Richard Potter: America’s First Black Celebrity. You can help independent bookstores and the New England Historical Society by buying it here.

With thanks also to Playing with Race in the Early Republic: Mr. Potter, the Ventriloquist by Paul E. Johnson, The New England Quarterly, Vol. 89, No. 2 (June 2016), pp. 257-285. Image of Ragged Mountain By Tom Morgan – Self-photographed, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5121853. This story was updated in 2023.