On Aug. 23, 1813, vessels in Salem Harbor flew their colors at half-staff. Thousands of people lined the shore looking toward the brig Henry at anchor as two barges were cast off bearing the black- draped coffins of Capt. James Lawrence and Lt. Augustus Ludlow. The two naval officers were killed several weeks earlier in the epic sea battle between the USS Chesapeake and HMS Shannon, just off the Massachusetts coast.

draped coffins of Capt. James Lawrence and Lt. Augustus Ludlow. The two naval officers were killed several weeks earlier in the epic sea battle between the USS Chesapeake and HMS Shannon, just off the Massachusetts coast.

As the barges made their way to Crowninshield Wharf (also known as India Wharf), cannon from the Henry and the USS Rattlesnake, a 14-gun brig of war, exchanged minute salutes. They fired a cannon every minute in homage to the officers. Sailors in blue jackets and blue trousers rowed to Crowninshield Wharf, their strokes slow and precise. Their caps bore the motto “Free Trade and Sailors’s Rights,” a slogan with glaring political overtones.

Crowninshield (India) Wharf, where the procession began

At the end of the wharf, the two coffins were placed on carriages for a procession through the streets of Salem.

Not everyone in Salem was happy at the heroes’ return, largely depending on their political party.

James Lawrence Killed in Battle

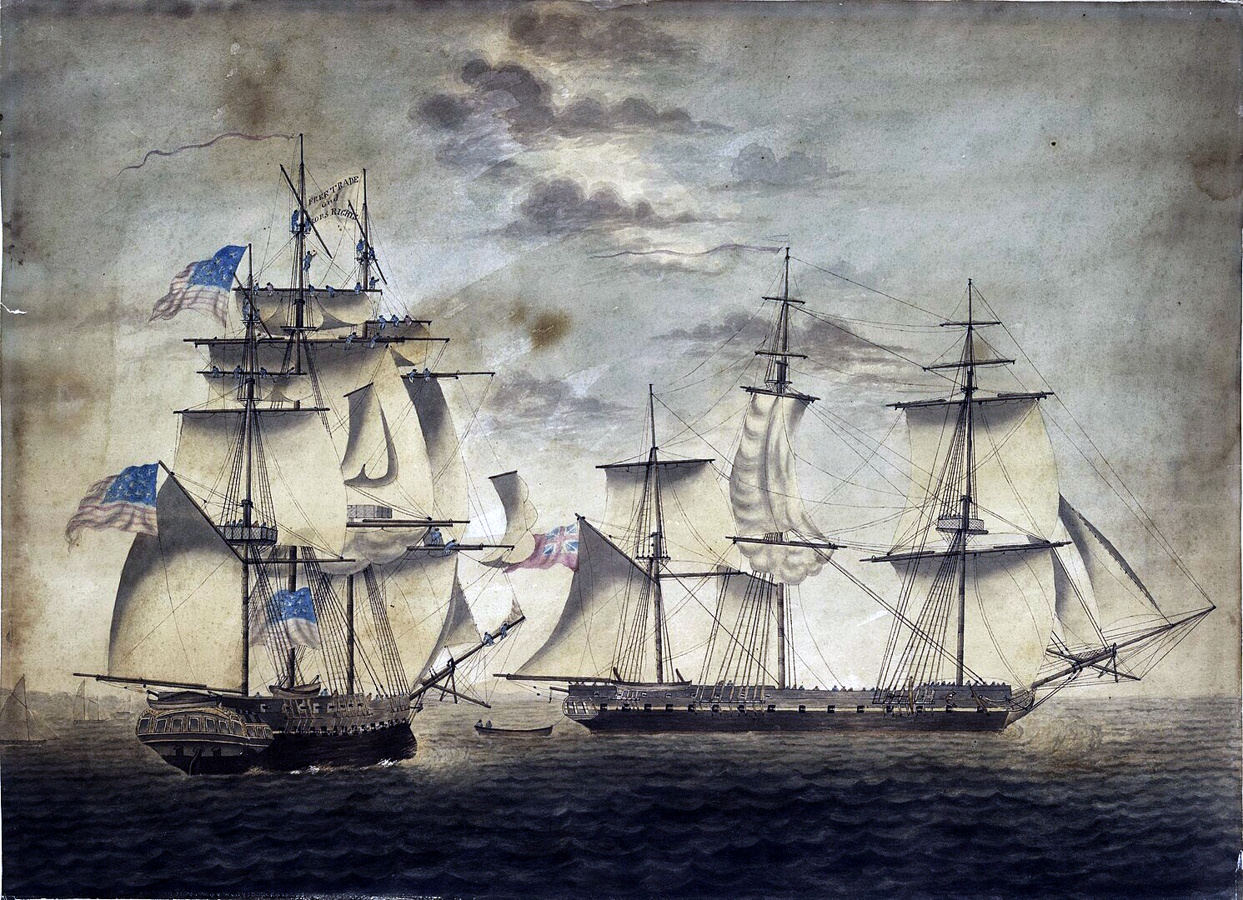

The battle between the frigates Chesapeake and Shannon took place weeks before on June 1, 1813. Lawrence was newly appointed to the Chesapeake as was much of the crew. But he was eager to take the fight to the enemy cruising in Boston Harbor with impunity. Both ships were roughly equal in tonnage and armaments.

Capt. James Lawrence, USN

Eager crowds onshore watched the Chesapeake leave Boston, the ship flying the U.S. colors and a large flag proclaiming the Free Trade slogan. As the battle commenced, the Chesapeake suffered serious damage from the first British broadside, which wounded Captain Lawrence.

USS Chesapeake

When the two ships came together, the British boarded the Chesapeake and in fierce combat overpowered the American crew, now almost leaderless with so many officers dead or wounded. As the mortally wounded Lawrence was being taken below deck, he was purported to give his famous order “Don’t give up the ship!” The whole engagement took no more than 15 minutes.

The Death of James Lawrence

The Chesapeake was claimed as a prize by the British and sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia. There the crew were imprisoned and Captain Lawence given a burial with full naval honors.

This was the first major naval victory for the British in the War of 1812.

Retrieval of the Heroes’ Remains

The War of 1812 was politically divisive in New England. The Federalists detested “Mr. Madison’s War,” while Democratic-Republicans (Republicans) were generally supportive. Salem was bitterly divided between the two parties.

The idea of returning Lawrence’s body to the United States, and to Salem in particular, was a Republican one. Several weeks after the battle, George Crowninshield, Jr., asked the Madison administration for permission to travel to the enemy port of Halifax to retrieve the body of Lawrence for reburial on American soil. Crowninshield offered the brig Henry under his command and at his own expense for the journey.

Crowninshield’s father founded Crowninshield and Sons, a shipping business of worldwide reach, trading with China, Russia, India, and the East Indies. They were ardent Jeffersonian Republicans and supported President James Madison.

Under a flag of truce, the Henry arrived at Halifax on August 10, 1813. The British were cooperative and polite, but insisted that only Crowninshield be allowed on shore. Three days later, the Henry departed Halifax with the bodies of Lawrence and Ludlow on board.

George Crowninshield, Jr.

The Henry arrived at Salem Harbor just before sundown on August 18, where it remained at anchor just below Crowninshield Wharf. A Committee of Arrangements scheduled the funeral for the following Monday, August 23. Perhaps anticipating the Federalist response, the Committee asked the public, regardless of class or party, to show proper respect for the heroes who gave their lives in defense of the country.

That was a tall order for the Federalists, who feared that honoring Lawrence’s sacrifice could be seen as support for the war.

Where To Hold the Funeral?

The Committee of Arrangements, perhaps naively, petitioned the North Meeting House at the corner of North and Lynde Streets for permission to hold Lawrence’s funeral there. It was the largest church in the town and had a fine organ, but it was a decidedly Federalist congregation. The request was turned down flat. In a letter of refusal, church elders replied that their meeting house was only open for public worship and no other purpose.

This was a blatant lie.

Charles S. Osgood and H. M. Batchelder in their Historical Sketch of Salem 1626-1879, state the North Meeting House was “frequently used for civic celebrations.”

Indeed, the Rev. William Bentley, the minister of the East Church and an outspoken Democratic-Republican, mentioned in his Diary that Samuel Putnam from the Committee of Proprietors of the North Church left town rather than witness the event. The Federalists, according to Bentley, particularly resented the Free Trade and Sailors’ Rights motto on the seamen’s caps. Even the Federalist governor of the commonwealth chose not to attend the ceremony.

The Rev. William Bentley

And typical of the political climate of the time, the Federalist Boston-Gazette wondered why any house of worship would encourage an unlawful and wicked war.

It was then decided to hold the service at the Congregational Branch Church on Branch (today’s Howard) Street.

Also, the Committee selected Associate Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, a Republican and long-time resident of Salem, to give the eulogy.

A Solemn Procession Through the Streets of Salem

The funeral procession formed at the wharf, led by an escort of six Navy captains, resplendent in their blue coats and gold braids. Commodores Isaac Hull and William Bainbridge walked beside Lawrence’s coffin, now draped in the national colors. Six naval lieutenants accompanied Ludlow’s.

Following were dignitaries, including Vice President Elbridge Gerry, military and naval officers, members of Congress, Justice Story, and representatives of local banks and insurance offices. Among the clergy in the procession was Reverend Bentley.

Some members of the East India Marine Society, the association of Salem sea captains and merchants, marched as well. But over a third of them voted to boycott the proceedings.

Despite the political controversies, citizens lined the streets along the way, and others looked from windows or stood on roof tops.

In the distance, minute guns sounded from Washington Square (Salem Common), while church bells rang out as the procession moved forward. A company of infantry also escorted the procession accompanied by a military band.

A view of Crowninshield (India) Wharf from the land.

The route to the Branch Church on Howard Street was a round-about one, allowing lots of people to see the procession. From Crowninshield Wharf at the foot of English Street, the mourners turned left along Derby Street, a crowded thoroughfare of wooden houses, taverns, and shops that ran parallel to the waterfront. Perhaps in deference to Reverend Bentley, the procession turned right onto narrow Hardy Street, allowing them to pass Bentley’s East Meeting House at the corner of Hardy and Essex Streets.

Church Bells Go Silent

Essex Street took the mourners westward towards the commercial heart of Salem. They went past the Brown Building, still standing, a large three-story, brick structure at the corner of Union Street, housing a bank, apothecary, and retail establishments. They then passed the brick Federal-style mansions of Joseph White, Gideon Tucker and the late Dr. Moses Little, all three still standing. Next came the banks, insurance offices and the customs building.

To their left, set back from the street, stood the enormous mansion of the late Elias Hasket Derby, with its towering cupula, huge Palladian window and extensive gardens. Beyond the Derby House, they passed the three-story First Church near the corner of Washington Street.

The First Church on Essex Street. The funeral passed by the front door.

Then at North Street, the procession turned sharply to the right heading northward. Feelings must have been running high as they approached the corner of North and Lynde Streets, where the North Meeting House stood. In a glaring example of the politics of the day, the church bells were silent – a snub to the passing mourners.

The procession continued eastward on Lynde Street, across Court Street (now Washington Street), then along Church Street towards St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, its tall tower housing Salem’s oldest church bell. Taking a slight jog to the right, the mourners entered Brown Street heading towards the Common, before turning left onto Branch Street and their destination.

An 1820 map showing the route for the funeral of James Lawrence and Augustus Ludlow

The Branch Church no longer stands, but was located on the west side of today’s Howard Street, just before the Howard Street Cemetery.

James Lawrence Funeral Service

At the church, the coffins were taken from the hearses and placed in the middle of the church by seamen from the funeral procession. The interior was draped in black and garlanded with cypress and evergreen. The names “Lawrence” and “Ludlow” were hung in banners of gold letters.

Joseph Story’s eulogy was long and in the overwrought style of the day. He recounted Lawrence’s and Ludlow’s lives and their heroic actions during that final battle.

Peace be to the spirits of the mighty dead – they

fell covered with honorable wounds in the cause of

their country.

After the service, Lawrence was temporarily interred in the Crowninshield family tomb in the Howard Street Cemetery. He was latertransported for burial at Trinity Church Cemetery in Manhattan.

Salem celebrates its 400th anniversary in 2026 and the 250th anniversary of Leslie’s Retreat in February 2025. Click here for more information.

James F. Lee, the author of this story, is a freelance writer and blogger whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, Boston Globe, Philadelphia Inquirer, and AAA Tidewater Traveler Magazine. He can be reached at www.jamesflee.com.

Sources for Funeral for Naval Hero James Lawrence

Salem and the Indies, James Duncan Phillips, 1947. Accessed online through Internet Archive.

An Historical Sketch of Salem 1626-1879, Charles S. Osgood and H.M. Batchelder, Essex Institute, 1879. Accessed online via Salem Historical Society Digital Books, HathiTrust.org.

An Account of the Funeral Honors Bestowed on the Remains of Capt. Lawrence and Lieut. Ludlow with Eulogy. Boston, 1813. Accessed online through Digital Archive, Toronto Public Library.

The Diary of William Bentley, D.D. Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts vol. 4. Gloucester, Mass, P. Smith, 1962.

Images

Shannon and Chesapeake, watercolor likely by Robert Dodd, 1813. From the New York Public Library www.digitalcollections.nypl.org. {{PD-US}}.

Wharf, George Ropes, Crowninshield’s Wharf. 1806, oil on canvas, Gift of Nathaniel Silsbee, 1862, M3459, Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum.

James Lawrence portrait, oil painting by J. Herring after Gilbert Stuart circa. 1812, Naval History and Heritage Command, U.S. Navy photograph http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/pers-us/uspers-l/j-lawrnc.htm {{PD-US}}.

USS Chesapeake, painting by F. Muller, circa 1900, Naval History and Heritage Command, U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-c/chesapke.htm {{PD-US}}.

Death painting, “Don’t Give up That Ship,” oil painting by Alfred Jacob Miller circa. 1840, source: Walters Art Museum {{PD-US}}.

Crowninshield, portrait, oil on canvas, attributed to Samuel F.B. Morse at Peabody Essex Museum. Author: Daderot, own work CCO1.0 {{PD-US}}.

Wharf from land, “India Wharf, Salem Ma” by Roy Cross, with permission from Marine Arts Gallery, 26795 S. Bay Dr., Unit 166, Bonita Springs, FL, (239)261-0000 Marine Arts Gallery.

First Church, Frank Cousins, Salem, “Washington and Essex Streets, views, town pump, and First Church,” circa. 1865-1914. Frank Cousins, Glass Plate Negative Collection, Photo Vault_Box 30_939, http://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/2b88rg90j.

1820 Map, map reproduction courtesy of Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center at the Boston Public Library, markings by author.