Portland Head Light has stood as a sentry to Portland Harbor since 1791, the oldest lighthouse in Maine. It can also claim to be one of the most photographed lighthouses in the world. The National Register of Historic Places

It’s one of only four authorized by George Washington and never rebuilt. Automated in 1989, today it includes light tower,

keepers’ quarters, whistle house, a paint locker and garage.

Want to know more? Here are seven fun facts about Maine’s iconic lighthouse.

1. It has had a lot of ups and downs — literally.

It was raised 20 feet. Then it was lowered. It was raised again. Then lowered. Then raised.

http://www.newenglandlighthouses.net/portland-head-light-history.html

Two stonemasons, Jonathan Bryant and John Nichols, got the job to build a 58-foot lighthouse for $700 in 1789 (the first lighthouse in Maine). They had to build it with local materials — granite and wood. to mark the entrance to Portland Harbor. When they finished, people realized it needed another 20 feet so ships could see the light. Bryant quit but Nichols finished the job in 1791. It went into service on Jan. 10, 1791, with whale oil throwing off a steady white light.

Then in 1812 a contractor named Winslow Lewis looked at the lighthouse and determined the top 20 feet were very poorly constructed. He suggested taking it off an putting in a new light. Lewis got the job in 1813 and designed a new lamp with reflectors and lamps. He sheared off 25 feet off the top.

In 1864, the wreck of the Liverpool cost the lives of 40 immigrants. An investigation found the lighthouse was too short. It was raised again by 20 feet and a new Fresnel lens installed. Then in 1883, the Lighthouse Board decided to remove the top 20 feet because it had deteriorated. Two years later, the board decided to raise it again.

Today it stands 80 feet above ground and 101 feet above sea level.

2. Keepers had to lock the doors to keep out nosy tourists.

In the 1950s, a woman barged in to the keeper’s house, sat down and demanded dinner because he was a government employee and she was entitled.

In the 1960s, the keeper’s wife forgot to lock the doors and took a bath. Tourists with cameras walked in on her in the bathroom.

Joshua Freeman, keeper from 1820-1840, kept a supply of liquor that he’d sell to tourists for three cents a glass. He kept a special bottle on a high shelf for visiting clergy — the “priest’s bottle.” (He also sat in his favorite chair with a coiled rope at his feet in case anyone needed a rescue.)

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who grew up in Portland, visited the lighthouse often. He would sit on his favorite rock and look out to sea, or chat with the lighthouse keeper. He wrote a poem, probably inspired by those visits:

The rocky ledge runs far out into the sea

And on its outer point, some miles away,

The lighthouse lifts its massive masonry,

A pillar of fire by night, of cloud by day.

About a million people a year now visit the lighthouse.

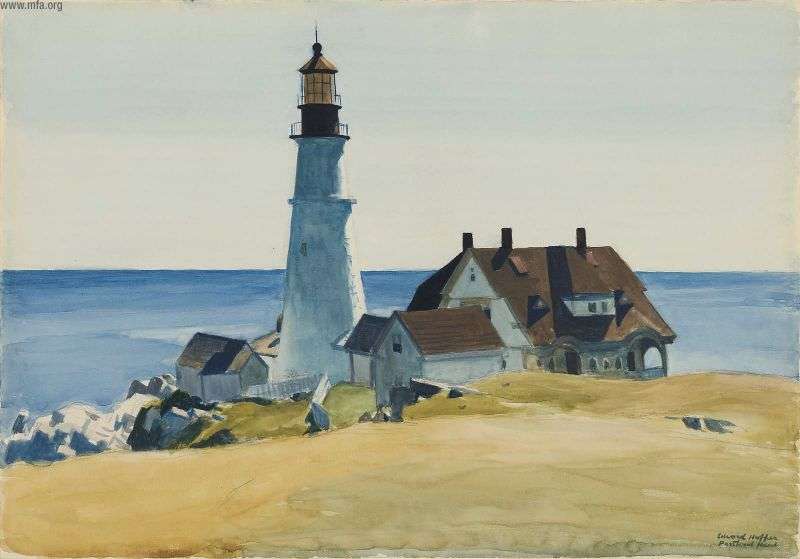

3. Portland Head Light inspired a great American painting.

Lighthouse and Buildings, Portland Head, Cape Elizabeth, Maine. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Critics consider his painting of Portland Head Light a masterpiece. It was even more than that — the inspiration for many, many more lighthouse paintings. “[I]t was Hopper who made of the lighthouse a representative and enduring American image,” wrote Carl Little.

Hopper painted the lighthouse in 1927 while on a visit to Maine. He painted a number of other lighthouses, including Two Lights nearby. He may have seen something of himself in the lighthouses. Hopper stood 6’5”, spoke little and didn’t and stood apart from the abstract painters of his day.

4.It didn’t prevent the wreck of the Annie Maguire, but it should have.

Of all the shipwrecks in Casco Bay, the tale of the three-masted bark Annie Maguire has the longest legs.

She wrecked just 150 yards from Portland Light on Christmas Eve, 1886, in air clear enough for the crew to see the light. Some speculate a brief snow squall caused them to misjudge the location of Portland Head Light. The crew, the captain and his wife — 18 in all — made it onto the ledge. The keeper, Joshua Strout, and his family brought them ashore by extending a ladder from the ledge. The Strouts brought them inside, made them take off their wet clothes, wrapped them in blankets and fed them.

The keeper’s son recalled that his mother had killed eight chickens for a huge Christmas dinner. She fed the crew with it. Recalled Strout’s son, “I only got one plate full. But we should worry. A feller doesn’t get wrecked often and when it happens where he can eat after starving for weeks, you can’t blame him for passing his plate until it is all gone.”

On board, the crew had been eating nothing but salt beef and macaroni with lime juice. Onshore, they stayed for three days and salvaged two cases of Scotch. Then they beat up the cook.

The vessel’s creditors only got $177 for the remains of the wreck. The sheriff searched for valuables in the ship’s sea chest but found nothing. Years later it turned out the captain’s wife had taken valuable papers and cash from the chest and sneaked them off the ship in a hatbox.

5. Four generations of one family worked at Portland Head Light.

For more than a century, at least one member of the Strout family had a job at the lighthouse.

Jane Dyer worked as a housekeeper for Joshua Freeman in the 1820s. She married Daniel Strout, and they had six children. They named their oldest Joshua Freeman Strout after the old keeper.

Joshua went to sea at age 11 and rose to captain. However, he fell from a masthead and suffered such severe industries he had to give up life at sea. He took the job as keeper of Portland Head Light in 1869. He then retired in 1904 after 35 years on the job.

His wife, Mary, worked as assistant keeper until their son, Joseph, took over in 1877. Joseph, known as Cap’n Joe, kept a parrot named Billy. When bad weather approached, Billy would squawk, “Joe, let’s start the horn. It’s foggy!”

Joseph succeeded his father as keeper in 1904, serving until 1928.

Joshua’s son John also served as assistant lighthouse keeper at several New England lighthouses. On one birthday, he painted an inscription to commemorate the wreck of the Annie C. Maguire. He chiseled away part of the rock to make a flat surface. He painted “In Memory of the Ship Annie C. Maguire, Wrecked on this Point Christmas Eve, 1886.” Then he put a cross on top of the rock. People have renewed the inscription over the years, shortening it to “Annie C Maguire, Shipwrecked Here, Christmas Eve 1886.”

https://www.southportland.org/online-services/learn-about/south-portland-historical-society/2013-articles/2015-articles/january-2015/

6. Keeping Portland Head Light was not a job for the faint-hearted

Old gun battery at Fort Williams

A hurricane almost killed Joshua Strout in 1869 when it knocked the fog bell from its base. In 1875, a storm knocked out the foghorn and extinguished the light. Storm-driven waves in 1975 and 1977 also snuffed out the light.

In 1872, the U.S. Army established a gun battery nearby, which grew into Fort Williams in 1899. The military usually notified the lighthouse keeper when it planned artillery practice, because shells would whiz by the keeper’s house and tower. The keeper’s wife would pack up the dishware, take pictures off the wall and remove anything on a table or bureau surface. The big guns blew out windows and tore off sections of roof and siding.

Thayer Sterling served as the last keeper from 1944-1946 until the U.S. Coast Guard took over. He lived there with his wife, Martha, and dog, Chang. One day during a storm, Martha sat knitting in her chair next to the window when Chang would not stop growling. She got up and moved away from the noise. Moments later a giant wave crashed through the window and threw shattered glass onto her chair.

7. 300 people can go into the light tower on just one day a year.

The public cannot go into the light tower except on one day, Maine Open Lighthouse Day in September. About 300 tickets are made available on a first-come-first serve basis the day of the event.

The museum and gift store, however, open from 10 am to 2 pm weekdays and 10 am to 4 pm weekends from Memorial Day to Indigenous Peoples Day. Admissions costs $2 for adults, $1 for children (6-18) and free for younger children.

Portland Head Light is actually in the town of Cape Elizabeth, by the way. It’s inside 90-acre Fort Williams Park, where visitors can hike along cliffs, explore the old fort or picnic on the grounds.

Images: Annie C. Maguire graffiti By Danazar – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75498874. Aerial view Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. Aerial view of Portland Head Light on Cape Elizabeth, one of the most-photographed places in Maine. United States Maine Cape Elizabeth, 2017. -10-18. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017883253/. Fort Williams By RobDuch – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=53326291. Portland Head Light black and white, Detroit Publishing Co., Copyright Claimant, and Publisher Detroit Publishing Co. Portland Head Light. United States Portland Maine, ca. 1902. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016799598/. Final Portland Head Light photo By Jubileejourney – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21849420.