Abbie Burgess, at just 16, kept the light burning in Matinicus Rock Lighthouse for 21 days in 1856 during a violent storm. While the tempest stranded her father on the mainland, she protected her mother and sisters from the violence of the wind and waves.

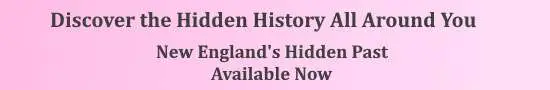

The government built the twin towers of Matinicus Rock Light in 1827 on the treeless and windswept Matinicus Rock, six miles south of Maine’s Matinicus Island. In 1846, granite towers and a granite keeper’s house replaced the wooden towers. President Franklin Pierce named Samuel Burgess lighthouse keeper in 1856. Burgess moved to the rocky outpost with his invalid wife, his son and three daughters, including, of course, Abbie Burgess.

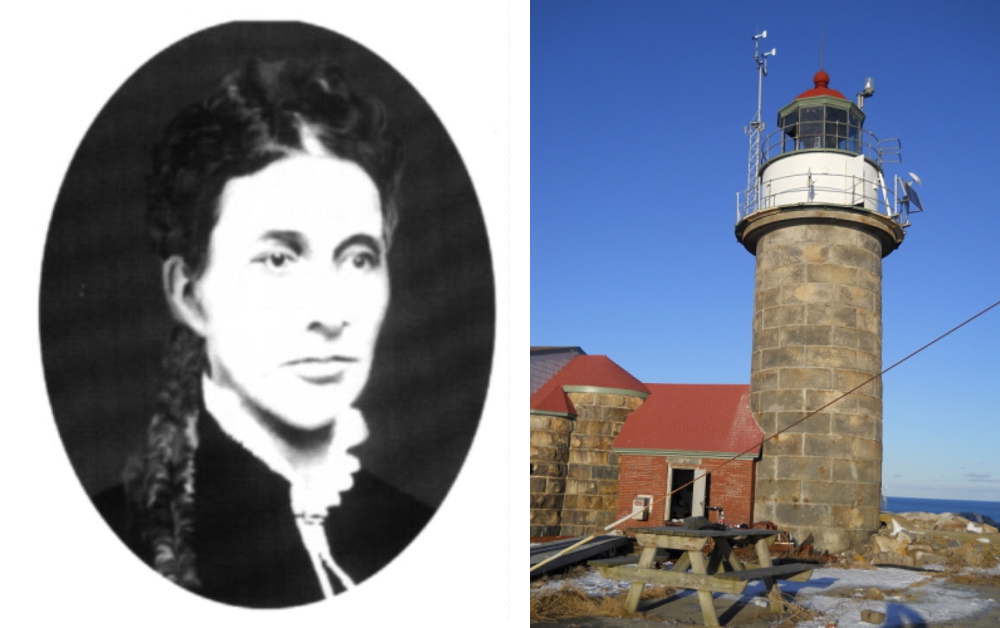

Abbie Burgess

Abbie Burgess, the oldest daughter, was born Aug. 1, 1839, in Rockland, Maine. She quickly learned to run the light, allowing her father to fish for lobsters and sell them in Rockland. Years later, she described the difficulty of tending the old lard lamps on Matinicus Rock.

…sometimes they would not burn so well when first lighted, especially in cold weather when the oil got cold. Then, some nights, I could not sleep a wink all night though I knew the keeper himself was watching. And many nights I have watched the light my part of the night, thinking nervously, what might happen should the light fail.

In all these years I always put the lamps in order and I lit them at sunset.

In January of 1856, while her brother had gone fishing, her father sailed to the mainland to buy food and oil for the lamps. Shortly after he sailed away the wind changed into a raging nor’easter. Abbie Burgess realized the danger and moved her family into the lighthouse.

The Terrible Storm

She wrote a letter to her friend Dorothy describing how they survived during the terrible storm:

…Early in the day, as the tide arose, the sea made a complete breach over the rock, washing every movable thing away, and of the old dwelling not one stone was left upon another.

The new dwelling was flooded, and the windows had to be secured to prevent the violence of the spray from breaking them in. As the tide came, the sea rose higher and higher, till the only endurable places were the lighttowers. If they stood we were saved, otherwise our fate was only too certain.

But for some reason, I know not why, I had no misgivings, and went on with my work as usual. For four weeks, owing to rough weather, no landing could be effected on the rock. During this time we were without the assistance of any male members of our family. Though at times greatly exhausted with my labors, not once did the lights fail. Under God I was able to perform all my accustomed duties as well as my father’s.

You know the hens were our only companions. Becoming convinced, as the gale increased, that unless they were brought into the house they would be lost, I said to mother: “I must try to save them.” She advised me not to attempt it. The thought, however, of parting with them without an effort was not to be endured, so seizing a basket, I ran out a few yards after the rollers had passed and the sea fell off a little, with the water knee deep, to the coop, and rescued all but one. It was the work of a moment, and I was back in the house with the door fastened, but I was none too quick, for at that instant my little sister, standing at the window, exclaimed: “Oh, look! look there! the worst sea is coming.”

That wave destroyed the old dwelling and swept the rock.

Matinicus Rock Light today

Cornmeal and an Egg

To fend off starvation, Abbie Burgess gave her mother and sisters a daily ration of a cup of cornmeal and an egg. Then after three weeks her father finally returned.

Samuel Burgess did not support Abraham Lincoln in 1860 and lost his job as lighthouse keeper. Abbie Burgess, though, stayed at the lighthouse as assistant keeper to John Grant. He had four sons and she married one of them, Isaac.

Together Abbie and Isaac worked as assistant lighthouse keepers. In 1875 they moved with their four sons to keep Whitehead Light for 15 years off St. George, Maine.

A Lighthouse Gravestone

Abbie Burgess died June 16, 1892 in Portland. In her last letter she wrote that she often dreamed of the old lamps at Matinicus Rock. She wondered if the care of the lighthouse would follow her soul after it left her worn-out body.

“If I ever have a gravestone I would like it to be in the form of a lighthouse or a beacon,” she concluded.

Fifty years later, maritime historian Edward Rowe Snow located Abbie Burgess’ grave in Forest Hills Cemetery in Thomaston, Maine. But it had no lighthouse or beacon as a gravestone. Snow placed a small lighthouse at her grave.

The Coast Guard named a buoy tender based in Rockland after Abbie Burgess. Authors Peter and Connie Roop wrote a much-loved children’s book about her, Keep the Lights Burning, Abbie. And today, Matinicus Island attracts visitors to view its puffins.

With thanks to Women of the Sea by Edward Rowe Snow. This story was updated in 2022. You may also want to read about Ida Lewis, the bravest woman in America, here.

Images: Puffin By Charles J. Sharp – Own work, from Sharp Photography, sharpphotography.co.uk, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=106949397. Matinicus Rock Light courtesy NOAA.