Capt. John Parker was dying of consumption when he led 70 militiamen against 700 British regulars during the Battle of Lexington.

Born July 13, 1729, in Lexington, Mass., he had lived 45 years and didn’t have one more left. But his military experience made him a natural choice to command the local militia. He had fought in the French and Indian War, then settled down as a farmer, mechanic and town officer. He and his wife, Lydia Moore Parker, had seven children.

His grandson, Theodore Parker, described him as “a great, tall man, with a large head, and a high, wide brow.”

On April 18, 1775, locals had seen redcoats in the area, including mounted officers. That night, Paul Revere and other express riders swarmed the countryside, spreading the alarm.

A messenger had roused Parker from his sickbed to tell him the British regulars had left Boston and were headed toward Concord.

John Parker left his house in the wee hours of April 19 and walked two miles to the Lexington Green. There, 30 militiamen — farmers mostly — waited in the dark for the arrival of British troops. Parker sent two men to scout the British. One returned saying he’d seen nothing. At the crack of dawn the other scout came galloping up the road shouting the regulars were just a mile behind him.

Parker ordered the drummer to beat a call to arms. He lined up his 77 militiamen in two lines on the Lexington green. Then he called the roll, and told them to load their firearms with powder and ball.

The British

Lt. Col. Francis Smith, commander of the expedition to Concord, had his own scouts. From them he learned the militia might try to oppose his troops on their march to Concord. He ordered a detachment of light infantry to march ahead under the command of Maj. John Pitcairn.

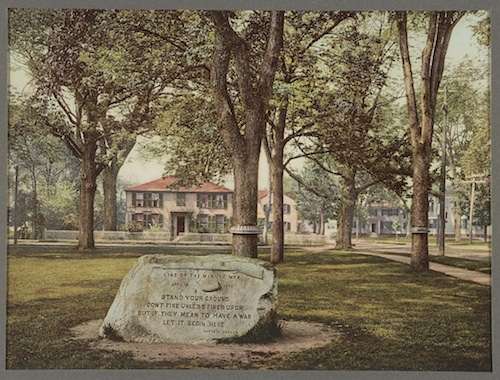

As the redcoats came into view, some heard Parker say, “Stand your ground. Don’t fire unless fired upon, but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.” Paul Revere, off to the side, heard him say, “Let the soldiers pass by. Do not molest them without they begin first.”

A British officer, probably Pitcairn, then yelled, “Throw down your arms! Ye villains, ye rebels!”

Parker ordered his men to disperse, but they didn’t all hear him, perhaps because his illness left him with a raspy voice. Some men had turned their backs when the famous shot went off. The redcoats fired at the militiamen and then charged with bayonets. Col. Francis Smith then arrived with the main body and saw British soldiers running amok. He ordered his drummer to play “Down Arms,” again and again. Finally the troops returned to their ranks.

John Parker saw his cousin, Jonas Parker, lying on the ground, bayoneted to death. Seven other Americans died, eight were wounded. Col. Smith ordered the men to march on to Concord to seize arms and ammunition. The British fired a victory volley and marched out of Lexington.

In Concord, 500 militiamen forced the British troops to retreat–back through Lexington.

Parker’s Revenge

Parker rallied his men, once they’d gotten over their shock and bandaged their wounds. They reformed along the road the British would take on their way back to Boston. When the redcoats appeared, Parker’s men fired on them from behind rocks and trees in an attack called “Parker’s Revenge.” One musket ball hit Lt. Col. Smith in the thigh and knocked him from his horse.

Archaeologists in 2017 located and mapped Parker’s Revenge. They concluded that the British were ordered to line up near the bottom of a granite outcrop. Parker’s men fired one volley, then turned and ran over the hill, planning to intercept the redcoats again. The British troops then fired a single time and ran after the militiamen, bayonets fixed. (Watch the video here.)

Colonial forces repeated those tactics as the British retreated, inflicting heavy casualties. They killed 79 British soldiers and wounded 174, losing 49 themselves over the course of the day.

Legacy

John Parker participated in the Siege of Boston, which began as soon as the British returned. But his tuberculosis progressed to the point that he couldn’t join in the Battle of Bunker Hill. He died on Sept. 17, 1775.

His grandson, abolitionist Theodore Parker, helped keep his memory alive. Parker inherited his eloquence, inspiring some of the most well-known speeches by Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, Jr. In the 19th century, Parker gave two of John Parker’s muskets to the commonwealth of Massachusetts. They hung in the Senate Chamber in the Statehouse until a renovation in 2018.

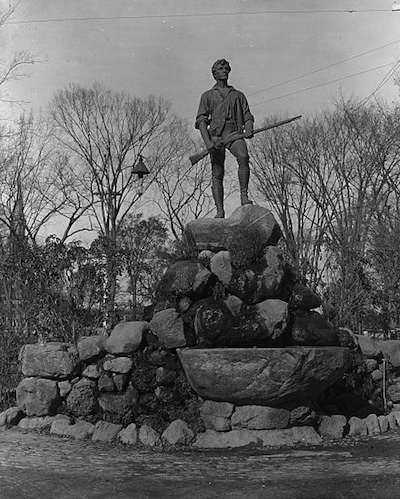

The statue The Lexington Minuteman, erected in 1900, is said to be modeled on Capt. John Parker, though there are no known likenesses of him.

This story was updated in 2021.