In the early part of the 20th century, entire church congregations from Americus, Ga., moved to Hartford during the great black migration north. Their pastors re-established themselves in the city as their parishioners got jobs in the surrounding defense plants and tobacco fields.

The story of an entire southern community migrating to a northern city is told often throughout the United States. From 1916 to 1970, 6 million African Americans moved from small southern towns to cities in the Northeast, Midwest and West.

For many, the great black migration was a journey from Jim Crow laws, lynchings, debt slavery and rural poverty to a somewhat better life in urban factories.

That, at least, is the simple version. In New England, the story gets a little more complicated. Migrants of color came not just from the American South, but from the Caribbean, Africa and the rural towns of New England. And they only came in large numbers until about 1930.

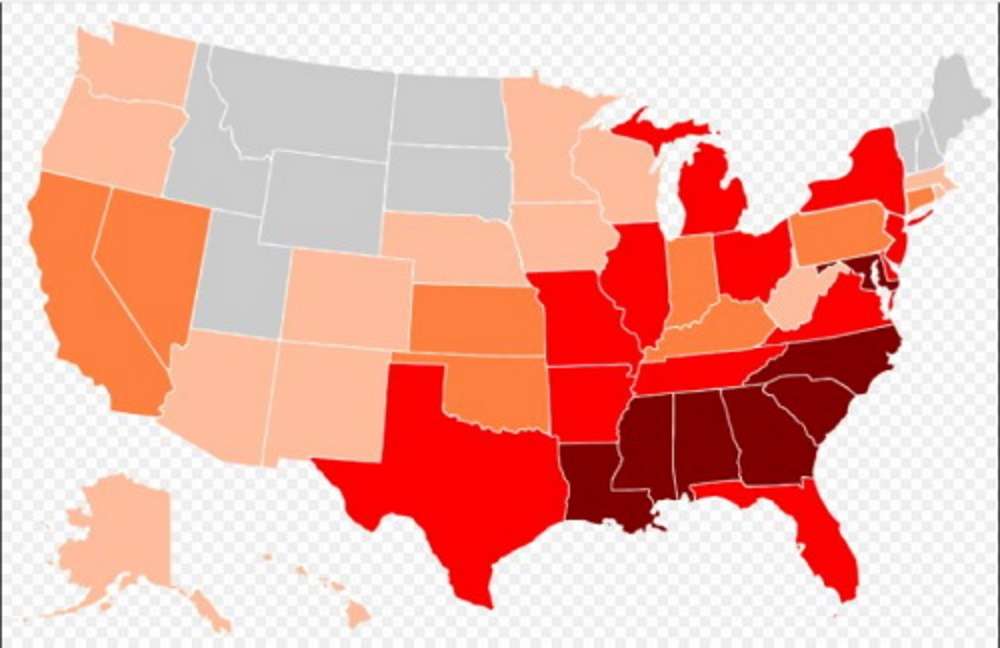

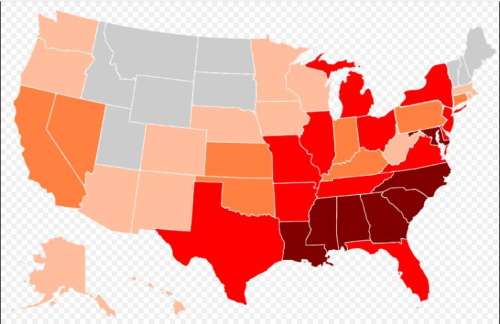

A map of the black percentage of the U.S. population by each state/territory in 1990. Black = 35.00+% Brown = 20.00–34.99% Red = 10.00–19.99% Orange = 5.00–9.99% Light orange = 1.00–4.99% Gray = 0.99% or less

Not Really Welcome

Before the great black migration north, people of color had already lived in New England. White New Englanders pushed them out with restrictive laws and few job opportunities. In 1755, for example, Africans made up 20 percent of the population of Newport, R.I., a major hub of slave trading. By 1900, only about 7 percent of Newport’s population was black.

The same held true in Hartford. Sociologist Charles S. Johnson wrote that Hartford had a larger black population proportionately in 1790 than in 1910. Whites took a “kindly and paternalistic” attitude to them, limiting their employment to servitude, he wrote. In 1800, blacks made up 4.5 percent of Hartford’s population; that number fell to 2.4 percent by 1900.

Boston was no different. In 1790, the year of the first census in that city, 4.2 percent of the population was black. In 1900, it fell to half that – 2.1 percent.

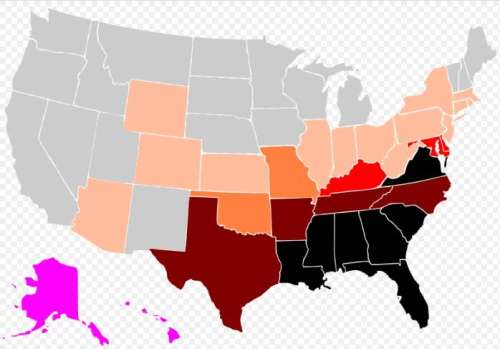

A map of the black percentage of the U.S. population by each state/territory in 1900. Black = 35.00+% Brown = 20.00-34.99% Red = 10.00-19.99% Orange = 5.00-9.99% Light orange = 1.00-4.99% Gray = 0.99% or less Magenta = No data available

But Boston’s African American population did grow slowly after the Civil War. Its strong abolitionist tradition attracted black people, and they were not legally denied the right to vote when the war ended. The Legislature In 1885 even passed a law forbidding discrimination in public places on the basis of race.

Such civil rights leaders as William Monroe Trotter, W.E.B. Du Bois and, later, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr., spent significant time in Boston. But they couldn’t prevent the decline of the Boston area’s manufacturing base, which drove its prosperity and provided at least some opportunity for people of color.

Big Cities

The North and the West experienced two great black migrations in the 19th century. The first started in 1910, swelled with the advent of World War I and then declined in the early 1930s. The second went from 1941, when wartime manufacturing again attracted black migrants, and lasted until 1970.

Only the first wave really came to New England. During the second wave, the only New England cities to experience slightly more than a one percent increase in their black populations were in Connecticut: Stamford, Hartford, Bridgeport and New Haven. And many New England cities saw a decline.

During that first wave, tens of thousands of African Americans from the South came to New England’s cities. But so did rural black New Englanders. Between 1915 and 1930, entire counties in New England became whiter even as the region as a whole got darker.

Train Arrive

During the first great black migration from the southern United States, most African Americans came by train. A statue of A. Philip Randolph in Boston’s Back Bay station testifies to the importance of the railroads as well as the African American Pullman porters who rode them. The porters shepherded the unsophisticated country folk to Philadelphia, New York, Bridgeport, Hartford, New Haven, Providence and Boston. Under Randolph, they also formed the first all-black union in 1925, a key development in the Civil Rights movement. (Malcolm X worked as a Pullman porter for about a year in 1943.)

The farther the black traveler went, the more it cost. That partly explains why Boston attracted a smaller percentage of African Americans than Philadelphia or New York—or even the southern New England cities.

Another reason Boston didn’t quite have the pull of industrial centers like Chicago or Detroit was that its manufacturing fell into decline. But Connecticut’s burgeoning defense industries were on the upswing.

From 1910 to 1940, the cities that experienced the largest growth in black population included Hartford, with a 23.6 percent increase. New Haven grew 22.4 percent and Bridgeport 13.8 percent. The others: Boston at 13.2 percent; Stamford 8.4 percent; New London, Conn., 8.2 percent; Waterbury 8.1 percent; and Providence 6.3 percent, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Today, Connecticut has the largest black population in New England. It rose from 1.7 percent in 1900 to 9.1 percent today, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Tobacco

One reason Connecticut, and Hartford in particular, attracted so many southern blacks: Connecticut shade tobacco.

Tobacco growers relied on European immigrants to harvest the tobacco around Hartford. But then World War I broke out, and immigrants who worked the tobacco farms returned to Europe to fight the war. Or they went to work in brand-new defense plants that paid 65 cents an hour and guaranteed two years of work.

The tobacco growers needed help, and they went for it to the National Urban League, formed in 1911 to help resettle black migrants.

The Urban League went to historically black college administrators like John Hope, president of Morehouse College, for seasonal tobacco workers in Connecticut. That began a long relationship with African-American students—like Martin Luther King, Jr.—who came to work summer jobs and get a taste of living free from Jim Crow. Eventually growers found they needed year-round workers, so southern black families began to move to Hartford.

But other than servitude and tobacco, the opportunity to get an industrial job in a tool or firearms factory ‘receded to an almost hopeless distance,’ wrote Charles Johnson, who in 1921 wrote The Negro Population of Hartford, Connecticut. But then in 1916, Connecticut’s factories faced a severe crisis as the labor shortage worsened.

Black tobacco workers drifted from the tobacco fields to the defense manufacturers, but mostly doing unskilled work in the coal yards and lumber yards, or as teamsters and porters. When the war ended, they got laid off first.

By 1921, 60 percent of companies surveyed hired no blacks, according to Johnson.

A Sociologist’s View of the Great Black Migration

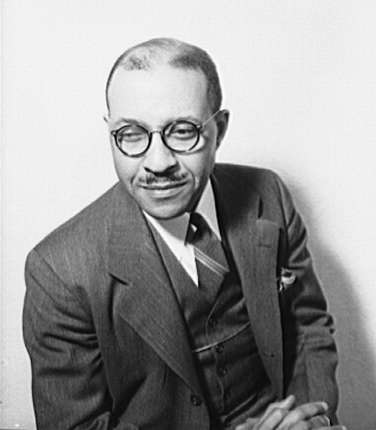

Johnson was the first black president of Fisk University. Before that, he studied the plight of those who came north in the first great black migration to Connecticut, focusing on Hartford.

Though the newcomers had many skilled tradesmen among them, they found jobs off limits to them at the Winchester Repeating Arms Co., New Haven Clock Co., and the New Haven Box Co. Some, like Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Co., Pratt & Whitney and the Royal Typewriter Co., preferred to hire African Americans only to perform unskilled duties such as custodial work, Johnson wrote.

Southern blacks had it harder than the Connecticut natives. The men wore overalls and women wore dust caps and aprons outside of the house—simply not done in the urban North.

The southerners, wrote Johnson, ‘were crude and ungainly, many of them boisterous, with strange habits of dress and manners altogether repellent to the older Negro residents inured to the refinements of the city.’

However, he wrote, the green soon rubbed off.

Most of the newcomers came from Georgia, but one-third as many came from Virginia. Americus, Ga., in particular sent blacks to Hartford.

Housing Problems

Southerners Johnson described as ‘crude laborers, loafers and ne’er do wells’ moved into neighborhoods vacated by the better-off natives.

The conspicuously successful, he wrote, didn’t live together, but forged close bonds with each other.

The newcomers lived along the Connecticut River in housing that Johnson described as among the oldest and most deteriorated sections of the city. Houses had few bathtubs or working toilets, and residents complained of leaking roofs, defective plumbing, fallen plaster and trash in the alley or yard.

Another neighborhood, the old red light district, he described as lower class but full of strivers. Hardworking families lived next to a ‘vicious and criminal element’— prostitutes, gamblers and bootleggers.

Southern blacks got blamed for anything bad that happened. “If a crime was committed it was assumed to have been committed by a Southern Negro,” wrote Johnson.

The Great Black Migration to Boston

During the Civil War, Boston had a black population of mariners, skilled craftsmen and servants who lived on Beacon Hill. Around 1900, they moved to the South End and Roxbury neighborhoods. Southern migrants, many from Norfolk, Va., joined them in Roxbury.

New England, and Boston in particular, had for centuries developed deep connections to Caribbean plantations. In the early 20th century, the United Fruit Company had a direct steamer service between Boston to Kingston and Port Antonio, Jamaica.

So Boston’s West Indian community began to emerge around 1910. Immigrants from Barbados and Jamaica moved into the Roxbury neighborhood and formed St. Cyprian’s Church, after white Episcopalians discriminated against them. In fact, black migration to Boston in the teens and 20s mostly came from the Caribbean, Cape Verde and South America.

Boston’s Second Wave

Some Southern blacks also arrived in the Boston area to work in the local shipyards during World War II. The Charlestown Navy Yard, for example, employed 2,000 black workers during the war, out of a total workforce of 47,000 people. The gigantic Fore River ship yard only hired black workers in the temporary auxiliary yards.

By the 1950s, Boston’s Afro-Caribbean population grew to 5,000 — 12 percent of the city’s black population.

But federal immigration laws passed in 1922, 1924 and 1952 restricted the influx of West Indians. Then in 1965, Congress eased the restrictive quotas. Family reunification laws allowed Jamaicans and Barbadians to come to Boston, settling in Crosstown in the South End and Cambridgeport in Cambridge. Then, as Jewish families moved out of Roxbury, Dorchester and part of Mattapan, West Indians moved in. They also moved to the Massachusetts cities of Randolph, Malden and Brockton.

In the 1970s, Haitians began migrating to Boston. By the 1980s, Boston had the third largest Haitian-American population in the country and the fourth largest Dominican-American population. Lawrence, Mass., and Providence also have a sizable Dominican presence.

Cape Verdean Communities

Cape Verdeans established communities in New England during the whaling days of the 19th century—New Bedford and Providence, especially, but also into Connecticut. The trickle of Cape Verdeans grew into a flood in the early 20th century due to poverty, drought and starvation. They worked in cranberry bogs, on the waterfronts and in the textile mills.

They moved to Hartford, where Charles S. Johnson found them in an undesirable neighborhood of African Americans from the South and Portuguese from the Cape Verdean and Canary Islands.

As in the case of Afro-Caribbean migrants, immigration restrictions slowed the arrival of Cape Verdeans in New England.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 initiated another great black migration: a new wave of Cape Verdean migrants. By 2010, New England cities account for every one of the 12 biggest Cape Verdean communities in the United States. In descending order, they are: New Bedford, Boston, Brockton, Pawtucket, Fall River, Taunton, Wareham, Providence, Randolph, East Providence, Central Falls and Bridgeport.

Former second baseman and manager for Major League Baseball Davy Lopes. He is of Cape Verdean descent and grew up in East Providence.

Universal Negro Improvement Association

Discrimination and inequality convinced many black people in New England they’d never receive fair treatment in the United States. A colorful, controversial Jamaican named Marcus Garvey had a message that appealed to them: they should be proud, they should achieve economic self-sufficiency, and they start another great black migration back to Africa.

Garvey in 1914 created the Universal Negro Improvement Association to spread his message. In Connecticut, it had active chapters in Hartford, New Haven, New Britain, Portland, East Granby, and Rockville.

Garvey also helped establish the African Orthodox Church in Boston. St James African Orthodox Church moved into the Highland Park neighborhood of Boston 15 years after Garvey died in 1940.

Civil rights lawyer Constance Baker Motley remembered her parents’ friends following Garvey. She grew up in the Dixwell neighborhood of New Haven. Her father, from Nevis, thought Garvey a fool.

A Great Black Migration to Africa

Going back to Africa wasn’t a new idea, and it wasn’t just an African idea. Thousands of African Americans resettled in the West African country of Liberia. Now many of their descendants have returned to Rhode Island

In the early 19th century, the American Colonization Society wanted to send ship former slaves to Arica. The ACS, in fact, helped found Liberia, where it sent shiploads of African Americans beginning in 1821.

Though most African Americans opposed colonization in Africa, some didn’t. A successful mixed-race entrepreneur, Paul Cuffe of Westport, Mass., supported the movement as well. He took 38 people from the U.S. black community to Sierra Leone in 1815.

In 1826, a group of Africans from Newport, R.I., left for Liberia. All perished of coastal fever within a year.

In the end, about 12,000 African Americans immigrated to the settlement that became Liberia. They declared independence in 1847 and in 1872 called themselves a free republic. The African Americans emerged as a political elite, but didn’t coexist peacefully with the indigenous people. From 1979 to 2003, Liberia went through bloody unrest, a coup, Ebola and two civil wars.

Great Black Migration from Liberia

Liberians started another great black migration to Rhode Island, the former slave-trading capital of the North American British colonies.

Rhode Island’s black population has more than doubled since 1900, from 2.1 percent to 4.5 percent. Pawtucket is 16.4 percent black, while in Providence people of color account for 13.3 percent of the population.

Now Rhode Island has the largest population of Liberians per capita in the U.S., which has an estimated 15,000 Liberians within its borders. The state, and particularly Providence, serves as the hub of the Liberian presence in the United States.

Late in 2019, Congress approved a Trump administration proposal to grant 4,000 Liberians a path to citizenship in the United States.

This story was updated in 2022.

Maps: 1990 By Blank_US_Map.svg: User:Theshibboleth – This file was derived from: Blank US Map.svg:, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20424896 By Blank_US_1900 Map.svg: User:Theshibboleth – This file was derived from: Blank US Map.svg:, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20424565; Davy Lopes By Keith Allison from Hanover, MD, USA – Dusty Baker, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58682216.