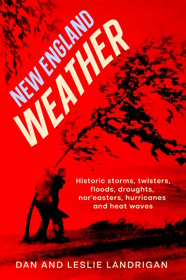

This story about the Blizzard of ’78 is an excerpt from the New England Historical Society’s new book, ‘New England Weather.”

Nothing like the Blizzard of ‘78 had ever occurred in New England before or after. It was a perfect storm, with hurricane force winds, a new moon, snow that fell for a day and a half—and mistimed weather forecasts that caused chaos on the roads.

By 1978, televised weather reporting had come a long way from the pretty bubbleheaded weather girls of the 1950s. TV stations were hiring real meteorologists from the National Weather Service, the military and graduate schools. But weather reports still had a way to go.

Meteorologists then didn’t have today’s dense weather monitoring network. Nor did they have sophisticated computer modeling—in fact, they didn’t have computers. They had fax and teletype machines.

So, in the late 1970s, weather forecasts often varied from TV station to TV station. One meteorologist might predict rain, and one might predict snow. Or they both might predict a snowstorm that didn’t materialize.

Forecasting the Blizzard of ’78

In the weeks before the Blizzard of ’78, some weathercasters had incorrectly forecast snowstorms. So, many people wouldn’t believe a storm warning until they saw snow.

On the weekend of Feb. 4-5, 1978, New England weathercasters predicted a storm on Sunday night, they just didn’t know how bad it would be.

Harvey Leonard, a rookie meteorologist with WHDH-TV in Boston, crawled out on a creaking limb and forecast a titanic snowstorm. “We are going to get hit hard,” he said.

The National Weather Service official forecast said there would be 6 inches of snow. A storm would develop on Sunday night and increase in intensity on Monday with a lot of blowing and drifting.

But no one saw snow early on the Monday morning of Feb. 6, 1978. People climbed into cars and buses and started their morning commutes. Tens of thousands of them wouldn’t make it back home for days. Nearly 100 wouldn’t make it at all. Another 4,500 would suffer broken bones, bruises, cuts and frostbite by the time it was all over.

The iconic image of the Blizzard of ’78 is a long string of stalled cars draped in a thick blanket of snow on a highway. The frozen traffic jams went on for miles: in Massachusetts on Route 128, Route 138 and Route 1; in Rhode Island on Interstate 95, Interstate 195, Route 146, the connector road to the airport and central Providence.

Route 128 during the Blizzard of ’78

Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis called the traffic mess on Route 128 “unbelievable.”

“It is as if there has been a massive rush-hour traffic jam and somebody had said, ‘Stop’ and covered the cars with 5 feet of snow,” Dukakis said.

Harvey Leonard was able to see it coming because he identified a low-pressure system traveling up the East Coast over warm Gulf Stream waters. Meanwhile, polar air was diving down from Canada. The two systems would collide off the New Jersey coast and spawn a behemoth nor’easter. To make things worse, a high-pressure system in eastern Canada would block the storm from moving on.

To qualify as a blizzard, snow must be falling or blowing about, visibility must be under a quarter of a mile and winds had to be above 35 mph.

It was a blizzard all right.

33 Hours

Once the snow started falling on Monday morning, it didn’t stop for 33 hours. New England got 2 feet of snow and in some cases 4 feet. Sometimes the snow fell as fast as 4 inches an hour. Parts of Boston’s South Shore and Woonsocket, R.I., got hit with 54 inches.

At 11 a.m. on Monday the National Weather Service put out a revised forecast for severe storms and flooding along the coast. The seas would rise 20 feet at high tide, it said.

People finally woke up to the seriousness of the storm. They left school and work early so they could get home, but the snow fell so fast that staying put was safer. The stupendous snowfall had made every major highway in Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island impassable. The cars and trucks trapped on the interstates along the Boston-Providence corridor would stay entombed for days.

Late in the afternoon, the National Guard opened several armories along Route 128 to use as emergency shelters. By nightfall, hundreds of guardsmen had fought through the storm to the nearest arsenal. Some took snowplows, some snowmobiles, some hiked, while some brought the Guard’s wreckers and four-wheel-drive vehicles. The guardsmen, who didn’t have winter parkas or boots, began to evacuate motorists to the armories, which didn’t have cots.

For the thousands stranded in cars, civil defense officials put the word out over CB radio that they should bunch up four to a car. They could run the engine for 10 minutes an hour to keep warm.

Some didn’t get the message. Fourteen died of carbon monoxide poisoning while running their engines in their snowbound vehicles. The snow piled up and blocked their exhaust pipes. Others died trying to walk to shelter.

Governors in Command

Days after the 1927 Vermont flood, three men from Massachusetts parked behind the Pavilion Hotel in Montpelier. An older man drove up, and they told him they planned to drive to Burlington. He said, “You will not be able to get over the railroad or highway out of the city for two weeks.”

“Do you live here?” one of the men asked.

“I guess I do. I am the governor,” he replied.

The governor, they said, looked very downcast.

In 1978, no elected official would be caught dead driving around looking disconsolate in a disaster. During the wall-to-wall news coverage of the Blizzard of ’78, politicians used the media to show they had command of the crisis response.

On Monday night the blizzard got worse, pelting New England relentlessly. Snow blew sideways. Winds roared and whined like sirens from Maine to Massachusetts. Windspeeds reached 79 mph at Logan Airport and 93 mph at Chatham Weather Station on Cape Cod. Unofficial reports said wind gusts exceeded 100 mph.

Meteorologist Bruce Schwoegler admonished WBZ-TV viewers to stay home during that harrowing Monday night. “If you go outside tonight, you gotta be out of your gourd!” he exclaimed. No one else would make it into the television station until the weekend. Schwoegler and the news crew slept at the station and wore the same clothes for five days.

Shelby Scott tried to make a run for it that night. She drove home on the back roads, cars slipping every which way. A half mile from her house she ran into an enormous snowbank. A snowplow came by, and the driver yelled, “Is that you, Shelby?” He got her out.

Tragedy

In Salem Harbor, the Greek tanker Global Hope foundered in 30- and 40-foot waves as the wind shrieked. A 44-foot Coast Guard patrol boat went to help Global Hope, but it lost its radar and power. Hearing on marine radio that the patrol boat was in trouble, the Can Do, a 49-foot pilot boat, plowed through the roiling waters to rescue the Coast Guardsmen. The Coast Guard also sent a 95-foot cutter, but it got lost in the whiteout. The cutter crew prepared to die. However, they made it to shore safely, and so did the patrol boat. Global Hope rode out the storm. But all five hands aboard the Can Do perished. “Mayday! Mayday!” they called before their radio went silent.

High winds drove the tidal surge over seawalls and breakwaters north of Boston in Revere and Winthrop. Roads and homes crumbled under the relentless pounding surf. The water rose fast. People climbed onto their roofs, screaming for help.

Ginny Deveau was sitting in her living room in Revere as the waves and wind rocked her house. “Then, this one wave hit,” she told a Boston Globe reporter. “It roared and whined like a siren. The house groaned and I knew it was time to get out.”

The Blizzard of ’78 Settles In

Dukakis happened to be on a radio call-in show with David Brudnoy on that awful Monday night.

Revere residents called in to the Brudnoy show from the second floor of their flooded houses, begging for help and wondering if they’d survive.

Michael Dukakis

As panic set in, Dukakis began to direct the emergency response on the radio. “I am pleading with Winthrop Shore Drive residents to evacuate their homes!” he said.

In the flooded cities, guardsmen, firefighters and police rushed from house to house, carrying children, women and the elderly through water that sometimes reached their necks. Amphibious vehicles took the victims to safety through flooded streets. Three thousand evacuees went to Revere High School that night as their houses bobbed up and down in the swirling, slushy seawater.

At 10:30 p.m., Dukakis declared a state of emergency. By then, 70,000 people in Greater Boston had lost heat and power. Every civil defense and emergency shelter in Massachusetts was activated and filled with 17,000 frightened people and their pets.

Overnight, the storm made a tight loop along the coast and settled south of Narragansett Bay. Snow and high winds continued to bombard the coast from eastern Maine to Long Island.

Before sunrise on Tuesday, Massachusetts guardsmen waded through waist-deep snow on Route 128, clearing off car windows and peering inside to see if their occupants needed medical attention—or were still alive. They began to help people from their cars into buses, which drove behind snowplows to emergency shelters. Two thousand ultimately went to St. Bartholomew’s Church in Needham, Mass., where they slept in the pews.

Guardsmen took 300 to the Showcase Cinema in Dedham, Mass., just off the highway. There they ate popcorn and watched movies as the blizzard rampaged outside.

First light on Tuesday revealed shocking damage along the North and South Shores of Massachusetts. Northeasterly winds and tremendous tidal surges had smashed through sea walls and swallowed whole neighborhoods in Gloucester, Revere, Lynn, Hull, Scituate and Plymouth. Waves had pounded through dunes and hurled boats hundreds of feet onto shore. They split houses in half, flung cars into the surf and shattered piers and boardwalks.

The stalled storm had blocked the high tide from going out much on Monday evening, and the tide was rising again. Things would only get worse along the coast.

Early on Tuesday morning, Dukakis put on a sweater and took the short ride from his Brookline duplex to the emergency operations center near the Statehouse. Television news crews waited for him. Dukakis went on the air at 8:50 a.m. announcing he was calling up the entire Army National Guard. An hour later he stood in front of the cameras again and banned travel in Massachusetts except for emergencies. He would make many more such television appearances, always in his sweater, over the next six days.

At Dukakis’ side was his public safety secretary, Charles Barry, a former Boston police captain. Barry was obsessed with emergency planning. That was fortunate for Dukakis, a 44-year-old first-term governor with little interest in disaster preparedness. Ten days before the Blizzard of ’78, Barry had insisted on presenting his just-completed, 5-inch-thick emergency response plan. He wanted a half hour to tell the cabinet about it. Dukakis reluctantly gave him 20 minutes.

After the Blizzard of ’78, Dukakis admitted Barry told him exactly what to say during his media appearances.

Inside the command center, phones rang incessantly with calls pleading for trucks, for snowplows, for cots, for blankets, for lifeboats, for help.

Help Arrives

Convoys from Fort Devens fought their way through the snow and the snarled traffic to the flooded coastal cities and towns. Once they arrived, they found that rocks, debris and icy waters made streets impassable, rescue difficult. In some places scuba divers swam through seawater to get to people in flooded buildings and take them to lifeboats.

Then came Tuesday’s high tide—a whopper. The moon wasn’t just new, it was a supermoon—as close to the earth as it gets. Tides rose 16 feet above normal, and the driving snow didn’t let up.

In Scituate, firefighters hauled the Lanzikas family and their neighbor, Edward Hart, into a skiff. A giant wave tore 5-year-old Amy Lanzikas from her mother’s arms. Amy and Edward Hart drowned. His body wasn’t found until April.

At least Cape Cod got a break on Tuesday morning. The raging nor’easter had turned into a hurricane. The eye passed the coast near Nantucket, bringing calm and sunshine to the Cape for a while. And then the furious winds returned.

Looting had started in Boston and elsewhere. Police could do nothing. The heavy snow, still falling, immobilized their cruisers. National Guard military police units came to their aid. Police officers and MPs together took four-wheel-drive vehicles through the snow-clogged streets looking for thieves. By early afternoon on Tuesday, police and guardsmen began arresting looters in Boston.

Around 4 p.m. on Tuesday, President Jimmy Carter declared Massachusetts a disaster area. That allowed federal troops to help with rescue and recovery. Guardsmen went to work clearing a runway at Logan Airport so military transport planes could land.

On Tuesday night, WBZ-TV reporter Dan Rea stood on the tarmac as flashing lights illuminated the still-falling snow. The U.S. Army was on its way, he reported.

Through the night and the next day, 36 Army aircraft landed, one by one, and delivered soldiers from Fort Bragg and the Army Corps of Engineers. They also brought desperately needed front end loaders, dump trucks, graders and wreckers. Each plane took off quickly so the next one could land.

Late on Tuesday night, the snow finally stopped falling. Blue Hill Observatory outside of Boston recorded the last flake just before midnight.

The Blizzard of ’78 Sets Records

The blizzard set snowfall records in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, while Connecticut fell short of the Great White Hurricane of 1888. As much as 2 feet of snow had also fallen in Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York and the rest of New England.

Though the snow had stopped on Wednesday morning, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut remained at a standstill. Roadways had disappeared under the snow, and the interstates were frozen parking lots. Many people were still trapped in their workplaces, living off vending machine food.

The military police unit on Cape Cod could only make it into Boston on Wednesday by following National Guard bulldozers and state public works plows.

But now that the sky had cleared, the air filled with helicopters. They crisscrossed eastern Massachusetts from morning to night. The helicopters took patients to hospitals, brought food to emergency shelters, assessed the flood damage and searched for bodies along the coast. Fenway Park was transformed into a heliport.

Dukakis climbed into a helicopter to survey the South Shore and Route 128. He was shocked. “You have to see it to feel it,” Dukakis said. “It was as if some giant had picked up all those little houses along the coastline and just flung them all over the place.”

Damaged houses along the seawall in Scituate

On the Scituate and Hull waterfronts, flooding had pulverized buildings, boats and piers, leaving a deep pile of wet rubble. Homes were ruined down to Long Island.

One flood tide had run into the next. With four successive flood tides, it seemed the tide never went out.

And still another high tide was coming. The Army Corps of Engineers and civilian volunteers filled sandbags in Hull, Quincy, Marshfield, Scituate, Revere and Winthrop. They piled them up to prevent more flooding where seawalls and breakwaters had been smashed to bits.

It was Ash Wednesday. Bishop Bernard J. Flanagan of the Worcester Catholic Diocese granted a dispensation. Catholics could wait until the weekend for fasting, abstinence and ashes.

Northeastern airports were still closed and would be for days. Boston Mayor Kevin White, on vacation in Florida, could only make his way home slowly from Palm Beach. White won little sympathy by complaining Florida was so cold he couldn’t swim in the pool.

The postal service couldn’t deliver mail for the first time since the Great New England Hurricane of 1938. One mail carrier got stranded in a post office, so he slept on sacks there for two nights. He fielded a phone call from a woman complaining she didn’t get her mail.

Soldiers, guardsmen, plow drivers and tow-truck drivers worked all day Wednesday and through the night. They cleared Massachusetts Routes 128, 138 and 1, cutting guardrails to get the abandoned vehicles out of the snowy gridlock. By Thursday morning, they’d freed a thousand stuck cars and trucks. It took a week working around the clock to clear all the roads in Massachusetts. Some plow drivers worked seven days in a row, stopping only to take catnaps. Some guardsmen worked 48 hours straight. Morale was high, though, and it was even higher when they received $100 cash advance payments on Friday.

The Town of Weymouth, Mass., asked private snowplow operators to donate their services. If they didn’t, town officials said, they’d confiscate their plows.

Massachusetts Digs Out

By Wednesday night, 6,000 Massachusetts guardsmen were on active duty. Many had come from homes damaged in the blizzard. Without adequate winter clothing, some suffered frostbite. The commonwealth bought 2,000 pairs of wool socks and lip salve from a Maine supplier and airlifted it all to military police and equipment operators.

Guardsmen enforced the travel ban, which lasted for a week in eastern Massachusetts. The word went out: If you were caught driving, you faced a one-year jail sentence or $500 fine.

A man in Burlington went stir crazy and took a drive down I-93. A guardsman stopped him, forced him out of his car and made him walk five miles home. Before he set out, the guardsman handed him a note to put in his pocket. The note said, “This man is mentally incompetent.”

By Thursday, state officials had a handle on the extent of the destruction. In Massachusetts, 2,000 homes between Marblehead and Plymouth were destroyed or severely damaged and another 10,000 needed repairs. The South Shore and Revere took the hardest hits.

Scituate was such a disaster area the National Guard closed it off to keep out sightseers and looters. The storm surges had dumped sand 6 feet deep on Oceanside Drive. People who went to check on their flood-damaged homes found thieves inside taking televisions and furniture. They were the lucky ones. When Mrs. Joseph Conley returned to her home in Scituate, the storm had demolished everything but the toilet.

In Eastham, the high tide leveled the dunes at Coast Guard Beach, eradicating the bathhouse and the parking lot. Floodwater tore apart beach shacks and buried them in Nauset Marsh. The tides split Monomoy Island in two off Chatham and divided Pamet Road in Truro. Hardly a trace remained of the Outermost House, the cottage where Henri Beston wrote his classic nature book.

The SS Peter Stuyvesant, a refurbished 269-foot Hudson River cruise ship, sank off the South Boston waterfront. Part of Anthony’s Pier 4 restaurant, the vessel’s wine cellar, artwork and mementoes were all a waterlogged ruin.

On Cape Ann, the storm surges had demolished sea walls, eradicated beaches and crushed houses, hotels and cars. Rockport’s famous red fishing shack, known as Motif No. 1, washed into the sea.

On the Monday after the Blizzard of ‘78, Dukakis’ driving ban was still in effect. But people needed to get to work. Four hundred civilians shoveled off Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority tracks for $3 an hour. The MBTA, though wrecked in places, carried 50 percent more riders than it did on an ordinary day. The load strained the equipment so that the transit system had to curtail commuter rail service by 25 percent for two months.

The Blizzard of ’78 Hits Little Rhody

In Rhode Island, the storm hit Newport first but saved its worst for the northern part of the state. Woonsocket got 54 inches of snow, too much for the single-bladed plows of the 1970s to handle. The mayor on Thursday pleaded for payloaders and dump trucks to move snow, and heating oil for Woonsocket’s public housing authority. But trucks couldn’t make it to Woonsocket through the Providence bottleneck. There was no way into, out of or through the city.

Frozen traffic jams surrounded and isolated Providence. People had left work too late. Snow buried thousands of cars and trucks on the interstates and in large sections of the city. Sometimes police officers found a body in a stranded car. They took the corpse back to police headquarters, which also served as an emergency shelter and a makeshift hospital.

At least the phones worked in Rhode Island, and most of the electricity stayed on. People could telephone for help, but ambulances couldn’t get to the dead or the dying. Vehicles couldn’t move until the streets were plowed, and the streets couldn’t be plowed until the vehicles moved. Providence Mayor Buddy Cianci asked for people with snowmobiles to volunteer. A small band of snowmobilers took the sick and injured to hospitals.

Buddy Cianci

Twenty-thousand people were stranded inside Providence. They found shelter in the Providence College dorms, City Hall and Butler Hospital. Cianci ordered all the city restaurants to stay open. He stationed a police officer at one to make sure it did. City workers then bought food for the sick and elderly.

Gov. J. Joseph Garrahy had put on a red plaid flannel shirt on Monday morning and wore it all week. He didn’t leave the Statehouse until Wednesday morning, when the storm finally stopped. The pavement outside was cleared for a helicopter so he could survey the situation from the air.

Providence was busier in the air than on the ground that day, where the only motorized vehicles that moved were snowmobiles. National Guardsmen crisscrossed the sky in helicopters picking up 4,000 sick, injured and stranded people.

A few hours into the storm, Garrahy had realized the state wouldn’t recover by itself. He called the White House on Monday asking for federal help and then spent Tuesday trying to get it. Finally, late Wednesday morning, Army transport planes began to land on a cleared strip of runway at T. F. Green Airport. They carried heavy snow fighting equipment as well as ambulances.

Two thousand vehicles had to be cleared off the interstates alone. Garrahy had a list of priority roads for the arriving Army: Interstates 95 and 195 north to Pawtucket, East Providence through the Washington Bridge and Route 146 into Woonsocket. The connector road to the airport needed clearing and so did the center of Providence where I-95 comes through.

Joseph Garrahy

Though the equipment arrived on Wednesday, the soldiers didn’t start landing until Thursday. Not until Friday did all 500 sets of boots hit the ground in Rhode Island.

On Thursday, a northbound lane of I-95 was cleared, and a few cars moved by afternoon. Looters had gotten to the cars, targeting CB radios. Some people tried to drive around Providence, hindering cleanup. Mayor Cianci then restricted most of the city to business owners and essential workers. Police threatened to confiscate cars if their drivers didn’t have a good reason to be on the road.

Many truck drivers stranded on the interstate lived in their cabs for five days. Two-hundred fifty tractor-trailers sat at the Connecticut border waiting to make delivery to Providence. Food ran short in the city, especially milk, eggs and bread.

Some store owners charged extortionate prices. Garrahy, in his plaid shirt, went on the emergency broadcast system and told people to ask for a signed receipt if they were overcharged. His comments were interpreted in Portuguese and in sign language.

By Friday, I-195 had opened. Some tractor-trailers hitched chains to stalled cars and moved them out of the way so they could get through. Soldiers helped people start cars that weren’t towed. One vehicle caught fire under the Washington Bridge and a payloader put it out by smothering it with snow.

By Saturday, half the major highways in Rhode Island were still closed. Fuel trucks still couldn’t deliver to Providence and many homes ran low on heating oil. But a federal disaster team had set up in Providence City Hall, and heavy equipment was arriving. The team arranged to have convoys of fuel trucks drive behind heavy equipment to make deliveries.

Military reservists went to work in Providence over the weekend, sometimes for 72 hours straight. They finally cleared the roads. Railroad tracks were shoveled as well, and trains started running.

By 11:30 a.m. on Monday, Providence opened to the public for the first time in a week.

During his many media appearances, Joe Garrahy appeared pleasant and unruffled. His performance helped earn him re-election in 1981.

Years later, he donated his red flannel shirt to the Rhode Island Historical Society. It was displayed with a stick of deodorant and a packet of saltines in the breast pocket, just as it had been during the Blizzard of ‘78.

Storm Larry?

In Connecticut, they called it Storm Larry. It left 2 feet of snow on the ground, and winds reached 86 mph. Hartford got 17 inches in two days—a lot, but one-third of Woonsocket’s unofficial total.

On Monday, Connecticut Gov. Ella Grasso had been riding around in a state police car making public appearances. As the storm worsened, she headed back to Hartford to direct emergency operations from the Armory. The car got stuck in the deep snow on Farmington Avenue, a mile from the Armory. Grasso’s driver, Trooper Bill Taylor, said, “That’s it.”

Ella Grasso

“That’s not it,” Grasso said. The 60-year-old governor then got out of the car and walked alone through the blizzard to the Armory, the emergency operations command center. She arrived covered in snow. There she took charge. She called up 100 National Guardsmen to help with the plowing and asked President Carter to declare Connecticut a disaster area. She drove a plow.

At 9:45 p.m. on Monday, Grasso requested volunteers over NOAA Weather Radio: “Governor Grasso has requested owners of four-wheel drive vehicles to contact their local civil defense office or their nearest state police troop in this weather emergency situation,” the message said.

It was the first time anyone had used NOAA Weather Radio for that purpose.

Grasso sent a second message a half-hour later, declaring a civil preparedness emergency and asking schools and businesses to close.

‘Ella, Help’

The next morning, she sent a third message over NOAA Weather Radio, asking for people with four-wheel drive vehicles filled with gasoline to call their local hospitals and nursing homes. They were needed to drive nurses and doctors.

Grasso spent three days at the Armory, catching a few hours of sleep one night on the sofa. After the storm had cleared on Wednesday, she took a helicopter to survey the damage in eastern Connecticut.

In Montville, two young men on skis wrote a message in the snow. It spelled out, “ELLA HELP.” Grasso saw it from the helicopter. Afterward, she sent a note to the young men, saying she hoped they’d “retain an interest in matters of public concern throughout your lives.”

Meanwhile, at Bradley Airport, 547 soldiers from Ft. Hood in Texas were arriving with snowfighting equipment. Connecticut was soon in motion again.

Grasso appeared on television and radio nearly every hour during the emergency, showing how much she cared about Connecticut citizens. Voters responded to her “Mother Ella” image and gave her a resounding re-election victory in November. But her detractors may have also had it right with their “Ella the Fella” nickname. Grasso’s lieutenant governor, Robert Killian, posed a political threat to her. She made sure he didn’t have anything important to do during the blizzard.

For Dukakis, the outcome was different. He lost his bid for re-election in the Democratic primary. Dukakis later joked that his loss was punishment for the travel ban that kept husbands and wives together for seven days. He may have been right. Though people born nine months after the Blizzard of ’78 wear the “blizzard baby” badge with pride, there were actually fewer than average babies born in November 1978.

Shelter From the Storm

Many remember the storm fondly because it inspired neighborly kindness. People with cross-country skis, sleds and snowmobiles went shopping for their neighbors. They took people stranded in cars to emergency shelters and the sick and injured to hospitals.

In Hull, Mass., Lillian Willis and Joanne Fallon prepared meals in a local middle school for 1,400 people. They took 36-hour shifts over 10 days. On the fourth day, Willis’ shoes fell apart.

Scituate emergency shelters stayed active for weeks for the families left homeless by the storm. Few had fresh clothing. Harvard’s equipment manager sent a tractor-trailer full of Harvard gear to the town. For the rest of the year, it seemed half of Scituate wore crimson.

School wouldn’t open until the middle of the month, so kids played in the snow. UConn students made Star Wars sculptures. Harvard students drank beer in the streets. Brown students made an 8-foot-high snowman.

Brown students also did what many young people did during that blizzard. They jumped out of second- and third-story windows into the deep snow. According to one report, 4 percent of Brown students and employees needed medical attention during the week of the blizzard. In Uxbridge, Mass., Peter Gosselin, 10, jumped off his porch roof into the deep snow. He hit his head and died in a snowbank. He wasn’t found until three weeks later, when a mail carrier saw his mitten sticking out of the snow.

Garden Party

Many had a blast at Boston Garden, the biggest, baddest, most fun emergency shelter of them all. The Garden in February hosts the Beanpot, a Boston college ice hockey tournament. On February 6, 11,666 fans decided to brave the storm and watch the games. During the first contest, Harvard beat Northeastern as word spread that it was getting nasty outside. Some left, but many stayed to watch Boston University play Boston College. An announcement then came over the loudspeaker that the storm was getting worse. Many fans still stayed to watch the game.

Then came a third announcement: Everyone should stay put, because they’d never get home. Hundreds of fans, Boston Garden employees and sports reporters–nearly all men–slept in skyboxes and locker rooms for the next several days.

Rich Fahey, a concession worker, later described the temptation to stay. “There was free coffee, leftover hot dogs and popcorn. We knew where there was beer to be had. Card games had broken out all around the club. Really, what else does a man need?”

As Boston Globe writer Dan Shaughnessy pointed out, they used “combs and deodorant left behind by Terry O’Reilly and Wayne Cashman.”

By the time the Beanpot refugees left three days later, Fahey noted they were “pretty ripe.”

‘I Survived the Blizzard of ’78’

After the Blizzard of ‘78 ended, entrepreneurs quickly capitalized on it. One company made a board game called the Great Blizzard Travel Game, which at one point you could buy for $59 on eBay. Others made T-shirts that said, “I Survived the Blizzard of 1978.” Bumper stickers that said “We Survived the Blizzard of ‘78” were as ubiquitous as Michael Dukakis’ sweater.

Dukakis in reality had four or five sweaters. After the Blizzard of ‘78, people gave him a sweater whenever he appeared at a speaking event. He eventually gave 40 sweaters to Goodwill.

The storm’s effects “are burned into long memories and likely will remain for many years to come,” wrote Eric Fisher, chief meteorologist for Boston’s WBZ-TV news, in his 2021 book, “Mighty Storms of New England.” The Blizzard of ‘78 is the reason snowplows go on alert before a nor’easter hits, he wrote. It’s also the reason any mention of the word “snow” sends New Englanders rushing to the store for bread, milk and eggs.

***

The Blizzard of ’78 wasn’t the only monster storm to hit New England. Read about them in “New England Weather” from the New England Historical Society. Click here to order your copy today!

The Blizzard of ’78 wasn’t the only monster storm to hit New England. Read about them in “New England Weather” from the New England Historical Society. Click here to order your copy today!

Images: Boston City Hall By City of Boston Archives from West Roxbury, United States – Snow near City Hall, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65429193; Boston during cleanup By City of Boston Archives from West Roxbury, United States – Workers and residents during blizzard cleanup, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65420068. Women on top of snowbank, By City of Boston Archives from West Roxbury, United States – Women on top of snow drift near City Hall, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65420027