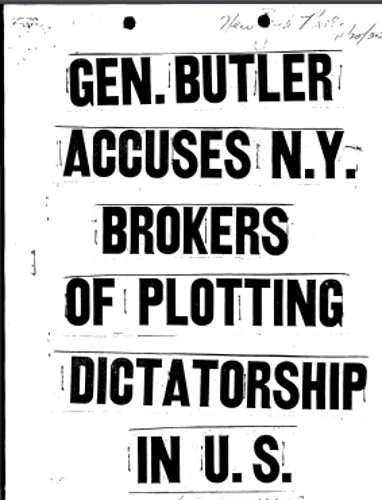

In 1934, Hitlerite paramilitary groups made headlines goose stepping their way around New York. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover got wind of Fascist conspiracies against the government. Then a Massachusetts congressman, 43-year-old John W. McCormack, had the unenviable task of investigating what came to be known as the Business Plot to overthrow the U.S. government.

German American Bund parade on East 86th St., New York City, 1939

McCormack honed his political chops with the Boston Irish political machine, and he knew a bad assignment when he saw one. “It was the last thing in the world I wanted to be chairman of, but I’m a soldier,” he told in interviewer in 1977.

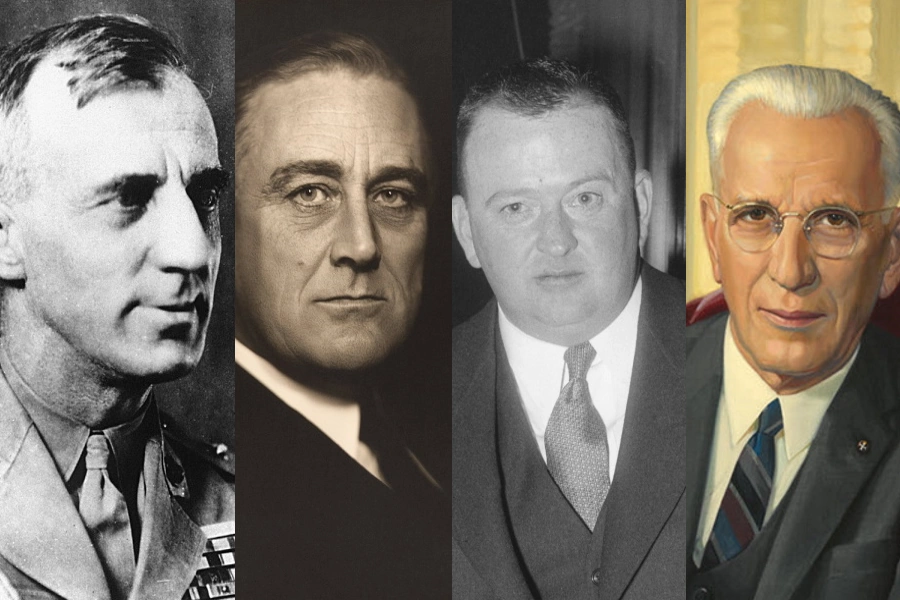

McCormack’s committee held hearings on a series of Fascist activities in the United States. The star witness in the hearing on Wall Street’s efforts to oust Franklin D. Roosevelt was an outspoken military hero: Smedley Butler. Butler knew a coup when he saw one – because he’d engineered them on behalf of the same capitalists who wanted to replace the president with a dictator.

Historical coverage of the Business Plot is thin, notes Grant Hamilton Stone in his 2021 thesis, Smedley D. Butler, Anti-Democratic Dissidence, and the Recession of the American Right 1932-1936. But he argues that it shouldn’t be overlooked.

“The Business Plot reminds us that threats to democracy have defined our past as much as they threaten democracy’s future,” concluded Stone.

The Man Who Exposed the Business Plot

Smedley Butler joined the Marines at 16 after the USS Maine blew up in Havana Harbor. In his 33 years with the Marines, he received five medals for bravery and the Medal of Honor twice. He became the youngest major general in the Marines at the age of 48. Charismatic and outspoken, his men nicknamed him Old Gimlet Eye. He was also known as the Maverick Marine for his clashes with civilian authorities and his controversial opinions.

Passed over for promotion to commandant of the Marines, Butler retired in 1931. Four years later he looked back on his career in the November 1935 issue of the magazine Common Sense.

I spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer; a gangster for capitalism. I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. I helped purify Nicaragua for the International Banking House of Brown Brothers in 1902–1912. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar interests in 1916. I helped make Honduras right for the American fruit companies in 1903. In China in 1927 I helped see to it that Standard Oil went on its way unmolested.

Smedley Butler

Smedley Butler in China

His experience in China may have soured him on U.S. adventurism that benefited big business. Warring forces had set the Standard Oil plant on fire, and the marines put it out. David Shoup, a decorated marine who served under him later recounted the China campaign.

“We didn’t know what the mission was,” Shoup said. “But we landed at the Standard Oil docks and lived in Standard Oil compounds and were ready to protect Standard Oil’s investment. I wondered at the time if our government would put all these Marines in a position of danger, where they might sacrifice their lives in defense of Standard Oil. Later I discovered that of course it would, and did. It was only some years later that I learned that General Butler had been thinking the same way.”

Smedley Butler inspecting Marine barracks in China.

After he resigned his commission. He began to speak to veterans groups around the country, ardently denouncing the government’s mistreatment of veterans. His popularity among military veterans and his outspokenness against the government put him on the radar screen of the men who hatched the Business Plot.

The Business Plotters

On July 1, 1933, Smedley Butler was at his home in Newtown Square, Pa., when he got a phone call from a man who said his name was Jack. Jack asked him if he’d meet with two veterans, William Doyle, head of the Massachusetts American Legion chapter, and Gerald MacGuire, former head of the Connecticut chapter. Butler agreed and shortly thereafter the two men arrived in a chauffeur-driven limousine.

Gerald MacGuire. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

They wanted Butler to deliver a speech challenging the leadership of the American Legion at its national convention in Chicago. They knew Butler – a critic of Legion leadership – hadn’t been invited. So they proposed a subterfuge: He could go as a delegate from Hawaii. The told him they had $100,000 to pay for veterans who couldn’t afford to go on their own. And they showed him the speech they wanted him to give. It defended the gold standard.

Franklin Roosevelt in the early 1930s

Roosevelt had taken the U.S. dollar off the gold standard in April 1933, a month after he took office. He hoped to reverse the deflation that had ravaged farmers and small businessmen who couldn’t repay their debts. Bankers, on the other hand, feared Roosevelt’s inflation would erode the value of their millions.

Butler later said he smelled a rat.

Jerry MacGuire

Butler learned more about MacGuire, a bond salesman from Connecticut, over the course of several meetings. Two months after their first meeting, MacGuire caught up with Butler at an American Legion convention in Newark and pressed him about rounding up veterans for the Chicago convention. He then tried to bribe Butler with a stack of thousand dollar bills.

Butler began asking him about his financial backers. MacGuire said he worked for Grayson M-P. Murphy, a wealthy investor with interests in the J.P. Morgan banking empire. He also gave up the name of Robert Sterling Clark, a Singer Sewing Machine heir who’d paid for MacGuire’s to visit Europe to study Fascist paramilitary groups.

Robert Sterling Clark

Butler agreed to meet with Clark near his home. Clark revealed to him the vague outlines of the Business Plot. He also told Butler who wrote the speech on the gold standard that MacGuire wanted him to deliver: John Davis, former candidate for U.S. president and currently chief counsel for J.P. Morgan.

The meeting ended badly. Carter offered to bribe Butler and baited him by saying “Morgan interests” preferred Douglas MacArthur for the role of dictator. Butler left in anger.

In the spring of 1934, Butler met with MacGuire again. MacGuire revealed the Business Plot. Butler would go to Washington leading 500,000 men, armed by Remington Arms and financed by DuPont, Carter and the Morgan interests. Roosevelt, intimidated by the show of force, would agree to name Butler “executive secretary of affairs” – in reality a dictator – and FDR would continue to serve as a presidential figurehead.

“If you get 500,000 soldiers advocating anything smelling of Fascism, I am going to get 500,000 more and lick the hell out of you, and we will have a real war right at home,” Butler said he told MacGuire.

Uncovering the Business Plot

In the fall of 1934, Butler contacted J. Edgar hoover about the plot.

What had most alarmed Butler was MacGuire’s reference to a new super-organization that would back the Business Plot. Weeks after their last meeting, Butler learned the American Liberty League had formed. It included a Who’s Who of right-wing capitalists: Grayson Murphy was its treasurer, Carter belonged, John W. Davis, Irence and Lammot Dupont, Alfred Sloan, Sewell Avery, a Morgan director. The American Liberty League created shell groups – what we would now call astroturf – organizations to oppose Roosevelt’s New Deal.

In addition to contacting the FBI, Butler did an interview with a Philadelphia Record reporter, Paul Comley French. French then interviewed MacGuire, who confirmed everything Butler told him.

A Closed Hearing

On Nov. 20, 1934, John W. McCormack, Sam Dickstein and the rest of the committee took testimony on the Business Plot in a closed meeting at the New York City Bar Association offices. McCormack had chosen Sam Dickstein, a Jewish congressman from New York, to co-chair the committee.

The McCormack-Dickstein Committee, forerunner of the House Un-American Affairs Committee, took testimony from Butler, MacGuire and French for five days. The congressmen also interviewed James Van Zandt, commander of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, who said he, too, had been invited to lead 500,000 veterans in a march on Washington.

John W. McCormack, official portrait as Speaker of the House

The committee found Butler credible, MacGuire not so much. Dickstein, speaking with reporters, said, MacGuire was “hanging himself with contradictions and admissions” every day.

Most of the news media, however, made light of Butler’s story. For example, The New York Times on Nov. 22, 1934:

A Washington correspondent asked: “What can we believe?” Apparently anything, to judge by the number of people who lend a credulous ear to the story of General Butler’s 500,000 Fascists in buckram marching on Washington to seize the government.

Report on the Business Plot

But In February 1935, the committee issued a report. In it, it said,

…evidence was obtained showing that certain persons had made an attempt to establish a fascist organization in this country. There is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient.

Dickstein later said they didn’t pursue the matter because they didn’t have the time or the money. The death of MacGuire on March 25, 1935, would have complicated efforts to learn more.

Roosevelt had some of the testimony redacted, perhaps because he didn’t want to stoke public outrage.

In 1935, Smedley Butler published his book, War Is A Racket. He died in 1940.

John W. McCormack became Speaker of the House in 1962 and served in that position until his retirement in 1971. He died in 1980.

With thanks to The Business Plot: Smedley D. Butler, Anti-Democratic Dissidence, and the Recession of

the American Right 1932-1936 By Grant Hamilton Stone, August 2021.

Images: Smedley Butler in China By USMC Archives from Quantico, USA – Smedley Butler Inspects Marine Barracks, Shanghai, China, 1927, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42678235.

This story last updated in 2023.