On the morning of May 23, 1939, the submarine USS Squalus slipped beneath the storm-tossed surface of the Atlantic on a sea trial. Minutes into the maneuver, she began flooding uncontrollably. The Squalus sank to the ocean floor nine miles off the New Hampshire coast, trapping 59 men on board.

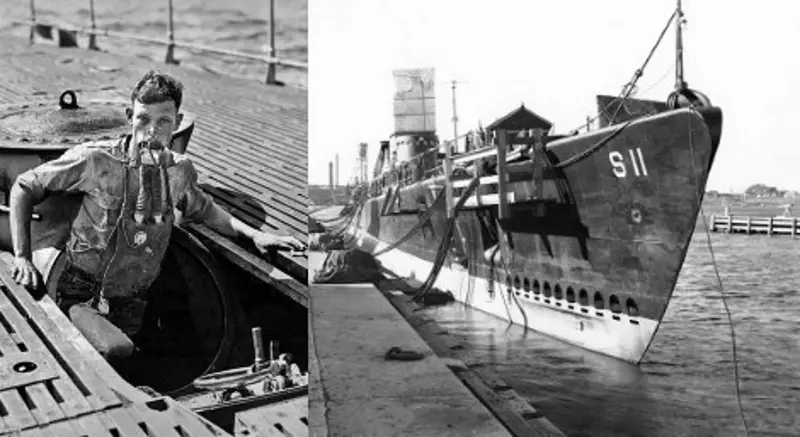

The salvage tug Falcon on the way to rescue the crew of the Squalus. Photo courtesy Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones collection.

For some of the Squalus crew, May 23, 1939 would be carved on their headstones. For others, it would mark a 39-hour ordeal they would live with for the rest of their lives. And for a hastily assembled Navy rescue team rushed to New Hampshire, it would be forever remembered as the date they launched an unprecedented rescue mission that stretched their abilities to new extremes.

Tears and Honors

No submarine rescue had ever succeeded beyond 20 feet of water. The Squalus was down 240 feet. The Navy team had to use new methods that had existed only in theory before that day. They encountered problems that forced them to make decisions on the fly—each with life-or-death consequences. And they did it all with the world watching intently, captivated by the fate of the trapped men whose plight had been broadcast around the world at telegraph speed.

Whether the men could be rescued before their oxygen ran out depended on an unproved diving bell, the seamanship of the crews, courageous divers, a quick-thinking admiral, a visionary submarine commander and the vagaries of New England weather.

In the end, the officers and men of the Squalus’ rescue and salvage team would receive four Medals of Honor, 46 Navy Crosses and one Distinguished Service Medal. There would be countless tears of mourning in the homes of those who did not survive the accident. And there would be a glorious new chapter written in the history of underwater rescue.

Newest Sub in the Fleet

Harold Preble left his rented cottage on Great Bay in Greenland, N.H., on the morning of May 23 and gave young Dorothy Emery a ride to school. She was his landlord’s teen-aged daughter, and she agreed to keep an eye on his sailboat for a few days. Preble would be joining the crew of the Squalus for routine sea trials.

Tall, spare and outdoorsy, he was the senior naval architect at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard a few miles away. He had ridden every new sub that left the yard for 22 years. Preble thought o the $5 million Squalus, the newest submarine in the fleet, as the best yet.

Named after a small shark with a big bite, Squalus launched before a cheering crowd at the shipyard in September 1937. Since then, she had performed successfully in 18 test dives, and no one expected trouble on the 19th. The sub was watertight, her systems worked.

The Squalus Commander

Her commander that morning was Lt. Oliver Naquin, a 35-year-old Louisiana native, once the hottest trumpet player at Annapolis. Now married with two children, he had charge of four officers, 51 enlisted men and three civilians – Preble and two electricians, one from the shipyard and the other from General Motors.

The Squalus got underway at 7:30 a.m. in choppy seas and a stiff wind. She then headed down the Piscataqua River and out to a point four miles past the barren Isles of Shoals. Naquin ordered the crew to rig the submarine for a dive and all hands assumed their posts.

At 8:40 a.m., Naquin gave the order to dive. The klaxon sounded, the hatch closed, vents opened and the Squalus went into a steep dive. Everything worked perfectly.

Preble turned to Naquin. “This is going to be a beauty,” he said.

‘Take her up! Take her up’

At 60 feet something went horribly wrong. The Squalus began to level off, and the crew in the forward compartments of the submarine felt a slight flutter. Suddenly Yeoman Charles Kuney heard over the battle phone frantic voices from the engine room. Someone screamed desperately, “Take her up! Take her up!”

The main air induction valve had opened, or failed to close, for reasons never discovered. Tons of seawater gushed into the engine room aft of the vessel.

The stunned crew paused for a moment, then frantically tried to raise the Squalus. They closed the flooded aft compartments and vainly tried to shut the induction valve. Preble and Machinist Mate Nate Pierce slammed levers to force compressed air into the ballast tanks to lift the stricken vessel. The Squalus stabilized and seemed to nose upward. Then, as the men tried to close leaks in the ventilation lines, pressure suddenly increased terrifically. Torrents of ocean water surged into the forward compartments, knocking down Preble.

The weight of the water in the aft compartments was too much. The Squalus began to sink to the ocean floor.

Squalus Blackout

Chief Electrician’s Mate Lawrence Gainor realized seawater was flowing into the aft battery room. Steam poured off the six-foot-high batteries and boiling acid rattled their caps. Gainor saw that the batteries were shorting out and would soon either ignite or explode.

He crawled through a narrow opening to the switches and turned the first battery off, setting off a miniature lightning storm. Half blinded and sure he’d be electrocuted, he shut the other switch off just in time. The entire sub immediately blacked out.

Lt. Naquin, clinging to a periscope, ordered Electrician’s Mate Lloyd Maness to close the watertight steel door between the operating compartment and the aft battery room. The North Carolinian held the door open shouting, “Hurry up.” His shipmates shouted back, “Keep it open! We’re coming!” They swam and clawed their way through the torrents of seawater to the safety of the operating compartment. Eight men made it through the door.

Maness then struggled to close it, his muscles quivering with the effort to hold back the floodwaters with a 300-pound steel door.

Finally the door shut with a click. Maness realized his friend, Torpedoman Sherman Shirley, was on the other side of the door. Shirley was to be married the following Sunday, and he had asked Maness to be his best man.

Maybe Shirley and some of the other men had barricaded themselves safely in the aft torpedo room, Maness thought. Maybe.

What Had They Done?

Later that morning at Portsmouth High School, the principal came into one of the history classes walking fast and looking tense. “We all glanced up from the maps we were drawing,” recalled Dorothy Emery. The principal called two students outside. The rest of the students wondered what these two had done wrong.

During the next period the principal grimly rushed into class again. He summoned three students from the classroom. “We couldn’t imagine what was going on,” wrote Emery in her book, Salt Water Farm: Memoir of a Place on Great Bay.

At recess, Dorothy found out from the children of Navy men and fishermen that the Squalus had gone down. The children called out of class all had fathers trapped at the bottom of the ocean. Classes were called off for the rest of the day.

The ‘Dreaded Hour’ Arrives

Lt. Cdr. Charles “Swede” Momsen was eating a ham sandwich for lunch at the Washington Navy Yard when the phone rang. He was a submarine rescue expert and head of the Experimental Diving Unit, and one of his divers was just emerging from a pressure tank. It was the final test of a 10-year-series of tests using a mixture of helium and oxygen to avoid decompression sickness, or the bends.

Commander Lockwood in Operations of the Navy Department was on the line. “Squalus is down off Isles of Shoals, depth between 200 and 400 feet,” he said. “Have your divers and equipment ready to leave immediately.”

Since 1921, 825 men had died in submarine accidents. No rescue attempt had ever succeeded. In 1925, Momsen commanded a submarine that made a futile attempt to rescue a sister sub rammed by a passenger ship. The officers aboard the doomed submarine were his friends.

Momsen had vowed to find a way to rescue trapped submarine crews. He invented an underwater breathing device, called the Momsen lung. And he conceived of the diving bell that he would use, for the first time, to try to rescue the Squalus crew.

Within two hours, Momsen boarded a seaplane at the Anacostia Naval Air Station in Washington. “The dreaded hour was here!“ he thought. “Would the dreams of the experimenter come true or would some quirk of fate cross up the plans and thus destroy all of this work?”

Terrors

Momsen’s plane landed in the teeth of a storm on the Piscataqua River that evening.

Fog forced another plane carrying a team of divers to land in Newport, R.I., 125 miles to the south. The divers jammed into three cars that screamed up the coast as state and local police blocked intersections. They drove so fast they lost the police escort in Boston. When they finally arrived at 4:15 a.m., one diver said, “After that trip, the terrors of deep-sea diving are nothing.”

Around midnight, Momsen reported to Rear Admiral Cyrus Cole, the shipyard commander.

Good Instincts

Cole’s instinct that the Squalus was in trouble, and his quick response, proved crucial to the rescue of the men.

He grew concerned when the submarine didn’t report surfacing on schedule at 9:40 a.m. He called the White Island lighthouse keeper, who couldn’t see a trace of the submarine.

At 11 a.m., Cole rushed to the dock where the Squalus’ sister sub, the Sculpin, prepared to depart for the Panama Canal a half hour later. Cole told the sub’s captain to pass through the vicinity of the Squalus and to try to make contact.

Cole called Washington to ask for the Navy’s best divers. Then he summoned the USS Falcon, a 187-foot minesweeper stationed in New London, Conn., 200 miles away. She would carry Momsen’s diving bell.

Squalus Sunk Here

Meanwhile, 240 feet beneath the surface of the ocean, ice formed on the bulkheads in the Squalus’ forward torpedo room. There, some of the survivors lay quietly under blankets in the dark. Others were in the control room, moving as little as possible. Most of them were wet, and all were cold. The toxic air caused some of them to vomit.

It was essential they preserve their strength. Lt. Naquin had figured they could last 48 hours if they didn’t use too much air. So he ordered the men to stay calm, to lie down, to try to nap, not to talk. They were to use buckets to relieve themselves rather than go to the head. Each man was given a Momsen lung and reminded how to use it.Men spread soda lime powder on the Squalus decks to absorb carbon dioxide.

Naquin stayed cheerful, smiling and asking after each of the men. He ordered them not to talk about the men trapped in the flooded engine rooms. Despite the frigid temperature, no one complained or expressed fear.

The survivors sent up signals for help. Naquin also ordered Lt. (jg) John Nichols to release a marker buoy from the deck of the boat. The three-foot yellow buoy was attached to a long cable and had a telephone in it. Big letters on the buoy spelled out, “Submarine sunk here. Telephone inside.”

As the buoy shot to the surface, a valve broke in the torpedo room and seawater gushed through, knocking down the cook. The crew hastily plugged the leak.

The Squalus crew sent up smoke rockets regularly, and blew slugs of oil out of the toilet bowl to supplement the smoke bombs.

Not one detail was overlooked, recalled one survivor. There was absolutely no excitement.

Two Options for Squalus Rescue

That first night, the vessels anchored on the search perimeter created a spooky tableau. Searchlights played along the inky surface of the ocean, illuminating the mist and the rain. Men looked for signs of the Squalus from the Sculpin and from the Coast Guard tugs Wandank and Chandler. Two Coast Guard patrol boats cruised outside the perimeter. As the fog rolled in, they wondered when the Falcon would arrive.

Aboard the Sculpin, Momsen considered the situation carefully. He knew he had to work fast. The ocean waters could breach the wreck and drown the men, or chlorine gas could poison them. And they were running out of air.

Momsen had rejected a proposal to raise the Squalus because it was too difficult and too risky. That left two options: The trapped men could don Momsen lungs and slowly ascend to the surface, or the rescuers could use the diving bell from above. If they went with the first option, the men would have to escape quickly through the hatch. They’d be weak and susceptible to the cold and pressure of the ocean waters. Some wouldn’t make it.

“On the other hand,” recalled Momsen, “rescue by the rescue chamber is safer, and there is less chance of losing men.”

That meant they’d have to wait on the slow-moving Falcon – and hope for better weather.

‘What’s your trouble?’

It was only by luck that the rescuers knew where the Squalus went down.

Somehow, the exact coordinates of the dive had been garbled in transmission to the shipyard. So Sculpin went in the wrong direction to search for signs of Squalus.

One lookout, Lt. (jg) Ned Denby, happened to glance in the opposite direction and thought he saw a smudge of red smoke. He whipped out his binoculars and confirmed it was a distress signal just as the smoke disappeared. The Sculpin changed course and raced toward the spot.

At 12:55 p.m., Sculpin recovered the yellow telephone buoy and then dropped anchor. The trapped submariners’ spirits rose because they knew the propellers they heard came from their sister ship.

Sculpin’s commander, Lt. Warren Wilkin, got on the phone. “Hello, Squalus. This is Sculpin. What’s your trouble?”

Nichols, the lieutenant (jg.) who had sent up the marker buoy, responded: “High induction open, crew’s compartment, forward and after engine rooms flooded. Not sure about after torpedo room, but could not establish communication with that compartment. Hold the phone and I will put the captain on.”

Thirty seconds later, Naquin got on the line. “Hello, Wilkin,” said Naquin. Then the cable snapped.

To continue reading, click on the link The Greatest Submarine Rescue Ever: Saving the Squalus (Part 2).

This story was updated in 2024.

14 comments

Hi,

I have a small brass model with a round base saying:

“May 23, 1939-Sept. 5. 1939 Squalus Salvage Unit”

It is about 10 inches long and 1 1/2 high.and 3/4′ wide.

I can’t find it described any where on the the web.

Can you tell me anything about its history?

Dominic

My Dad had a small model of the Squalus, also, and now my brother has it. Dad was a crewmember of the Sculpin on that day. I was told that small models of the Squalus were given to crewmembers who participated in that rescue. Very, very interesting story!

My Moms Uncle was in the rescue ship I think the Fakcon. He received tgeNsvy Cross for working the air hose for the diver! What an amazing story! My Moms Unckd was Ted Fickes

It says the link URL is wrong ?

^Thanks, we’ll check!

Incredible!!

Amazing story. Thank you for writing and putting this online.

shared

[…] The Greatest Submarine Rescue Ever: Saving the Squalus […]

[…] The Greatest Submarine Rescue Ever: Saving the Squalus […]

[…] The Greatest Submarine Rescue Ever: Saving the Squalus […]

[…] are red-rimmed from constant weeping,” reported the Hearst news service. “You can’t blame Lloyd Maness,” she said, referring to the sailor who had closed the compartment that trapped his friend […]

[…] Another tremendous rescue at sea took place 13 years earlier and about 100 miles to the north. Read about it here. […]

[…] members of the USS Squalus, this fear became a reality on May 23, 1939, after a routine sea trial off the coast of Portsmouth, […]

Comments are closed.