1.7K

This story about Anne Dudley Bradstreet was excerpted from the New England Historical Society’s book, Love Stories from History. Click here to order your copy today.

This story about Anne Dudley Bradstreet was excerpted from the New England Historical Society’s book, Love Stories from History. Click here to order your copy today.

From the tall windows of Sempringham Hall, eleven-year-old Anne Dudley could see out over the vast marshy fenlands of Lincolnshire. Sheep grazed on the low green hills, and horse-drawn wagons ambled along the road to town. Fifteen miles away, she could spy the tower of the most beautiful church in England, her church: St. Botolph’s Parish.

St. Botolph’s, Anne Dudley’s church

Every Saturday, her father took the family in an open wagon to hear John Cotton, St. Botolph’s esteemed minister. The Dudley family was among the most devoted of Cotton’s followers, known as Puritans.

Anne was a serious, devout girl, and she looked forward to Cotton’s sermons. He preached that they should steer their lives in the direction of the true God with pure and lively hearts. Anne knew she sometimes fell short of that ideal, and the thought tormented her.

John Cotton, Anne Dudley’s pastor

It was 1623, and Anne wanted nothing more than to please God, at least most of the time. Her duty to God and to the man she loved would take her to an awful wilderness across the sea. But Anne would reconcile with her fate—and win acclaim back in England. Today a wrought iron gate at Harvard University memorializes Anne, as do the thousands of people who read her poetry.

Anne Dudley

Anne’s father, the stern and ambitious Thomas Dudley, worked as steward for the twenty-four-year-old Earl of Lincoln, Theophilus Clinton. The young earl’s late father had run up so many debts that the estate was nearly worthless. But Thomas Dudley managed the young earl’s affairs skillfully and freed it from encumbrances. He was part lawyer, part secretary, part business agent and part property manager. The earl’s large family adopted him as a dear and trusted friend.

Dudley did his job well, but he needed help managing the earl’s tangled business affairs and sprawling properties. Which is why, one day, he summoned Anne and her siblings to meet his new assistant, Simon Bradstreet.

Simon Bradstreet

The new assistant was nine years older than Anne Dudley, and he seemed nice. Simon had a sturdy build, ruddy good looks and long flowing hair. Unlike her father, he liked to laugh, and he knew how to get along with people.

Simon was also well-born, with the manners of an aristocrat. He could carry on a learned conversation, and, like the Dudley family, he fit in well with the earl’s enormous Puritan household. Living at Sempringham Hall were the earl, the earl’s eight younger brothers and sisters, his mother, the Dudleys and fifty servants.

Anne’s Puritan beliefs put her on the constant lookout for signs of God’s approval or disapproval. Before Simon arrived, Anne had almost died. She came down with a fever and spent weeks in bed. During those long, lonely hours she not only suffered physically, but from thoughts that God was punishing her.

Bookworm

When Anne was sick, her father comforted her with books from the earl’s library. She had inherited his love of reading. He and Anne both devoured every book they could get their hands on—ancient philosophers, medical texts, poetry, a little Shakespeare and Greek and Latin classics.

Anne had studied alongside the earl’s younger sisters. Their mother, Countess Elizabeth, hired a tutor to teach them writing, classical history and literature. That they would read was a given. Puritans believed everyone should know how to read the Bible. But not everyone who could read knew how to write. It was a tricky business to apply ink to parchment with a bird’s feather.

Simon saw that Anne read books, and he started talking about them with her. He’d been to college and knew more than she did, but he began to think this serious, pious girl was special. They spent more and more time with each other, talking about the people in their lives, about books and about God.

He knew she was anxious about displeasing God, but that didn’t put him off. Rather, he thought her anxieties showed her saintly nature.

As she grew older, Anne’s feeling for Simon began to change. She started to want more than the comfort and companionship of an older brother. She started to think about her appearance, and she began to fuss over her pretty lace collars and her pearl hair ornaments. Anne knew Anne knew such feelings were sinful outside of marriage. But she couldn’t help straying from God’s path, and it terrified her.

Shocking News

One day when Anne was fourteen, Thomas Dudley made a shocking announcement. The family would move to the earl’s Boston townhouse. Simon would stay behind to manage Sempringham. He had proven himself exceptionally capable as Dudley’s assistant.

Anne didn’t want to leave the manor, the earl’s sisters, his library. Most of all she didn’t want to leave Simon.

God then sent Anne a message in Boston. She came down with a fever that turned into frightening delirium. Nausea and vomiting followed. Ulcers formed in her mouth, and a rash that spread over her skin turned into oozing blisters. Smallpox.

From Sempringham Hall, Simon followed Anne’s illness with concern. When he learned that Anne had begun to recover, he went to see Thomas Dudley and asked for her hand in marriage. Anne’s father happily said yes.

They married in a civil ceremony before Anne had fully recovered. At last, Anne could physically express her deep love for Simon within the sanctions of marriage.

Anne Dudley Bradstreet

It was an inauspicious time for a young Puritan couple. The old king, James, had sympathized with Church of England leaders who harassed Puritan ministers. His son, Charles, the new king, was worse. He silenced, fined and even imprisoned Puritan ministers. The Puritan faithful felt increasingly isolated in a corrupt and unforgiving country.

Nearly nine years earlier, a group of the most zealous Puritans had planted a colony at a place called Plymouth. They were struggling to establish a virtuous utopia for all the world to look up to.

Lincolnshire farmland

Amidst the religious turmoil, Anne was happy. She was married to the man she loved. And she loved the rolling green hills of Lincolnshire, the marshy fens, her church in town, the courtyards and gardens and great stone fireplaces. She had no desire to leave her paradise of plenty for a wilderness of want.

One day, Anne and Simon heard startling news. King Charles had imprisoned the earl in the Tower of London. The king had demanded money from him, and the earl had refused. For that he could be facing death. The king might also order the arrest of the earl’s stewards—Thomas Dudley and Simon Bradstreet.

Portrait of John Winthrop, American Antiquarian Society.

An urgent meeting of England’s leading Puritans was called at Sempringham Hall: John Cotton came. So did a wealthy lawyer named John Winthrop and three other ministers, Roger Williams, Thomas Hooker and Isaac Johnson, the earl’s wealthy brother-in-law. He had married Anne’s friend, the earl’s devout sister, Arabella.

They decided to emigrate to the New World. And once they left, there would be no turning back.

The New World

It took a year to get everything ready. John Winthrop would head a group of investors in the new colony. Thomas Dudley would serve as second in command. Simon would be secretary.

They sent an advance team of fifty planters and servants to clear land, plant crops and build houses. Those first colonists sent a few letters back to England full of cheer and optimism, but short on details.

Some of the Puritans who signed up to relocate looked forward to the clean air, delicate plums, abundant strawberries and healthful climate of the New World. Anne doubted.

Simon told her she had to sell her pearls, her silks and her treasured books. The proceeds paid for heavy woolen clothing for the North American winters and saltfish and beer for the voyage. Outwardly, Anne went along with Simon’s plans. Inwardly, she rebelled. She could not make her heart want to go.

Seven hundred people signed up to start the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Not everyone was a Puritan. They had learned from the Plymouth colonists that carpenters were essential for survival, as were armorers, bakers, blacksmiths, butchers, cordwainers and merchants.

The Winthrop Fleet

They would sail together in a fleet of eleven ships. The galleon Eagle would lead the way as the flagship, but Winthrop decided to rename it Arabella. He did it to honor Anne’s friend, the earl’s sister. Lady Arabella and Isaac Johnson had invested more than anyone in the Massachusetts Bay Company.

The Arbella, reproduction

Anne and Simon boarded at Cowes, but bad weather kept the vessel in port for a week. Finally on April 8 the weather turned, and the Arabella set sail. “Farewell, dear England,” the passengers cried as the vessel sailed into the Channel.

The eleven-week voyage was worse than Anne had imagined. Crowded together with lower-class strangers in a filthy, stinking hold, they couldn’t even clean up the inevitable vomit when a storm hit. With no privacy, Anne and Simon couldn’t satisfy their passion for each other, though some people did. Along with the stench and the filth came spoiled food, bad manners, profane language and frequent quarrels.

At least Anne was with Simon, and she had her Geneva Bible to comfort her.

Salem

Before dawn on June 12, 1630, the Arabella anchored a mile from shore in Salem Harbor. When the sun rose, all the passengers could see was a dark, featureless continent. No church spires, no houses, no boats moored along the waterfront. Anne didn’t know what to expect when she climbed into the tiny shallop that would row her to shore.

She was happy to leave the fetid boat, but she dreaded what she’d find on the land. The New World seemed devoid of any feature but huge trees, unlike any trees she’d ever seen before.

When the boat reached shore she was shocked at what she saw.

In a clearing stood a handful of hovels covered in old mats and sticks. There was just one normal house. The colonists tottered around lethargically. Some seemed drunk and disoriented, a symptom of scurvy—or maybe it was the tobacco they smoked. Some were invalids.

She soon learned that dozens of colonists had died the winter before. They had barely enough corn and bread to feed themselves for two weeks.

Some of the settlers lived in caves. They hadn’t built outhouses, just relieved themselves behind their hovels. The air stank.

Anne felt sick to her stomach. “My heart rose,” she later told her children. But she didn’t complain.

A Terrible Winter

Two hundred settlers died and another two hundred gave up and returned to England that first winter. Anne wished she could go with them. But she didn’t say anything to Simon.

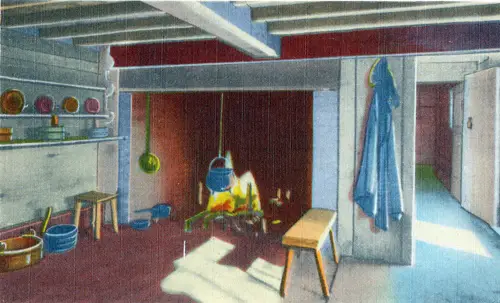

Postcard of a itchen in Salem’s Pioneer Village, a recreation of the Puritan settlement

The settlement called Salem was such a disaster that Anne, Simon and the other newcomers moved to an abandoned Indian village they called Charles Town.

Through the terrible winter, Anne and Simon shivered in a miserable hut, lived on shellfish and watched their friends die.

Many had gotten scurvy on the voyage, which worsened because of the damp and the lack of food. So many took sick that the healthy couldn’t care for them. One of the two hundred who died was Lady Arabella. A month later, her husband, Isaac Johnson, perished.

Worse than the mourning and privation was Anne’s knowledge that God was displeased with her. She wanted children, a bunch of them, to love and nurture to adulthood. Though she and Simon tried mightily, she couldn’t get pregnant. It was a great grief to her, and she cried and prayed over it.

The water in Charles Town turned out to be brackish. So when spring arrived, a man named William Blaxton, who’d gone to college with some of the Puritans, invited them to move near his spring. Winthrop took him up on his offer and named the settlement Boston.

Move to New Towne

Blaxton lived south of the river. Anne and Simon joined the Dudley family in moving north of the river to a place they named Newe Towne.

A carpenter built a two-room house for Anne and Simon, with thatched roof, a crude stone fireplace and a wooden chimney plastered with clay. It was part of a little cluster of houses just like theirs.

Working alongside the servants, Anne and Simon made their house a home. Simon cleared land, planted crops, chopped firewood, fed the livestock; Anne washed, spun, made clothing, cleaned, cooked, gardened, preserved fruits and vegetables. At night they nested like a couple of turtle doves. But as a merchant and administrator, Simon often had to leave home. Anne’s spirits fell when he was gone.

She almost didn’t make it through the second winter. She caught a fever and for months lay in bed, too weak to get up. Anne understood God was trying to humble her, and for that, she felt grateful. Her realization that she must accept her lot in the wilderness without resentment or anger brought her tremendous relief.

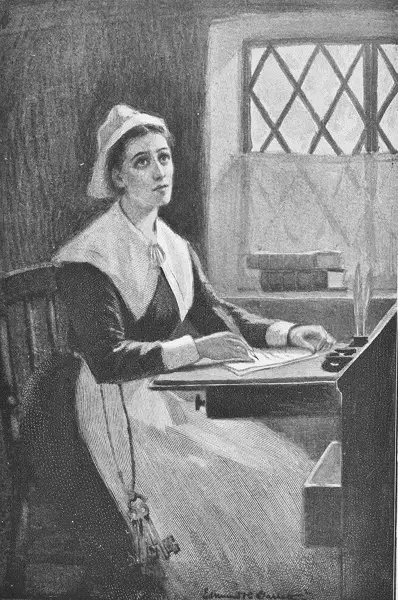

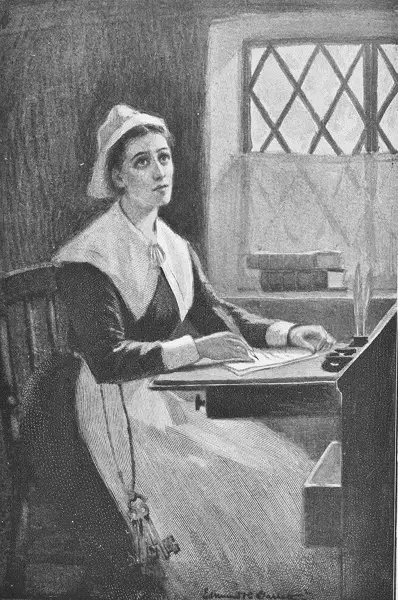

Nineteenth century depiction of Anne Bradstreet by Edmund H. Garrett.

Anne Dudley Bradstreet, Poet

Anne then did something unusual and difficult. She wrote a poem.

She had almost no spare time. No desk to write on. And she had to know exactly what words she’d write and how she’d draw the letters before she committed ink to a piece of parchment, rare and expensive in the wilderness of Massachusetts Bay Colony.

It was a freakish thing for a woman to do, but not unheard of. Simon praised her poem when he read it. She called it “Upon a Fit of Sickness.” Her minister and her friends read it, and they also approved.

The poem, “Upon a Fit of Sickness,” marked her acceptance of her life in the wilderness. Part of it reads:

O whilst I live this grace me give,I doing good may be,Then death’s arrest I shall count best,because it’s Thy decree;Bestow much cost there’s nothing lost,to make salvation sure,O great’s the gain, though got with pain,comes by profession pure.

And then Anne got pregnant. She gave birth to a healthy boy she named Samuel. And then a girl named Dorothy, after her mother.

For the next six years, Anne didn’t write a single poem.

The years passed. Anne and Simon had six more children. They improved their house and their land. Nearby, Simon and her father started a college called Harvard. They founded two more towns in Massachusetts, Ipswich and Andover. Her house burned down, and Simon was elected governor.

More Puritan families arrived in ships, built houses, started more farms and founded fifty towns. A decade after Anne and Simon arrived, twenty thousand settlers had erected churches, a castle, a college and a prison in Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Then thousands of Massachusetts Puritans started going back to England, including half the Harvard graduates and a third of the ministers.

The English Civil War

Civil war had broken out. On one side the king’s army fought for the king’s right to rule with absolute power. On the other side, Parliamentarians fought for a constitutional monarchy. Puritans were almost all Parliamentarians. And so Puritans left Massachusetts to fight.

Then the two sides wanted to end the fighting, and negotiations were set to take place on the Isle of Wight. The Parliamentarians needed a neutral chaplain for the talks. They decided to find someone from the Massachusetts colony, and they settled on the Reverend John Woodbridge, who had married Anne’s sister Mercy.

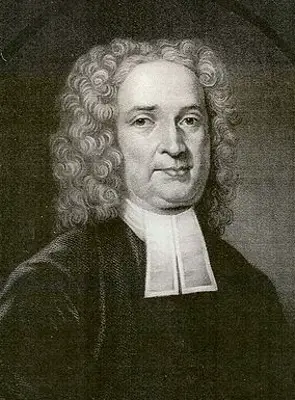

John Woodbridge, Anne Dudley Bradstreet’s brother-in-law

Woodbridge admired Anne’s poems, and he carried a collection of them with him across the Atlantic. He claimed she didn’t know he’d brought them. Woodbridge assumed no one would believe a woman could write such poetry. While in London, he asked about a dozen men of standing to endorse Anne as a pious and learned woman.

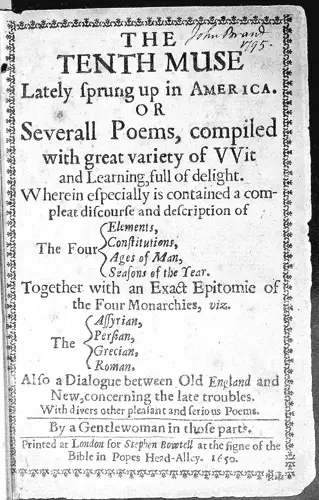

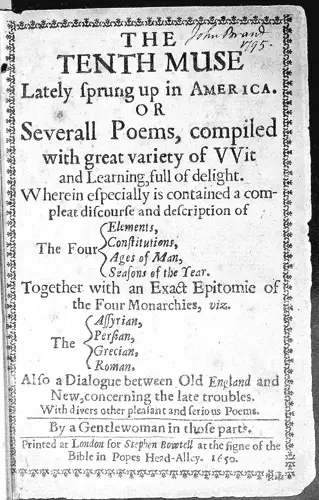

Woodbridge then submitted Anne’s manuscript to a publisher who, to his surprise, agreed to publish it. On July 1, 1650, a book the size of a woman’s hand went on sale in London under the title, The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America.

If there had been a best-seller list in 1650, Anne’s book would have topped it. Eight years after it appeared in print, The Tenth Muse was listed as one of the most saleable books in England. The book was popular in America, too, where for years it was said every Puritan household owned a copy.

Anne Bradstreet was now famous, but she kept up a modest front. She wrote a poem downplaying her poetry. It began, “Thou ill-formed offspring of my feeble brain.” But she didn’t apologize. And she kept writing. But all her manuscripts burned in a fire that consumed her house in Andover when she was fifty-four. She then wrote a poem about losing her house.

A Wilderness of Want

Anne Bradstreet led a beautiful life, people said. She and Simon carved wealth and honor out of a wilderness of want. She won the affection of her community as a serene and capable manager of her pioneer household. And she loved her children dearly, launching them successfully into the world.

But throughout her life, she struggled with her faith. Sometimes she felt herself turning away from God, distracted by earthly passions. After she first fell in love with Simon, she nearly died from smallpox. She decided she’d angered God, and he sent her illness to set her on the proper path.

When she secretly despised living in a colonial village in Massachusetts, God again reminded her to submit cheerfully—by nearly killing her again.

When her house burned to the ground, she blessed God, who gave and took from her. She didn’t need a house, she concluded in her poem,

Verses upon the Burning of Our House

The world no longer let me love,My hope and treasure lies above.

The Death of Anne Dudley Bradstreet

Anne died in Andover at the age of sixty. Simon lived for another twenty-five years. After several years of deep mourning, he remarried.

A few years after Anne died, another collection of her poems was published. Some of the newer poems had been too personal to publish while she was alive. One, a love poem, made no apology for her earthly passion for Simon.

People are still reading it.

To My Dear and Loving Husband, by Anne Dudley Bradstreet

If ever two were one, then surely we.If ever man were loved by wife, then thee.If ever wife was happy in a man,Compare with me, ye women, if you can.I prize thy love more than whole mines of gold,Or all the riches that the East doth hold.My love is such that rivers cannot quench,Nor ought but love from thee give recompense.Thy love is such I can no way repay;The heavens reward thee manifold, I pray.Then while we live, in love let’s so persever,That when we live no more, we may live ever.

***

This story about Anne Dudley Bradstreet was excerpted from the New England Historical Society’s book, Love Stories from History. Click here to order your copy today.

This story about Anne Dudley Bradstreet was excerpted from the New England Historical Society’s book, Love Stories from History. Click here to order your copy today.Images> St. Botolphs By The National Churches Trust – Lincolnshire, BOSTON, St Botolph, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=107127609. Lincolnshire farmland By Tim Heaton, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3934822.