A year and a half after U.S. and British troops invaded Normandy on D-Day, another invasion took ![]() place. Tens of thousands of war brides from Britain and Europe rejoined their husbands in cities and towns throughout the United States. Herded onto ocean liners, they disembarked in New York City, hundreds at a time, and then, if they were lucky, their husbands met them and took them to their new home.

place. Tens of thousands of war brides from Britain and Europe rejoined their husbands in cities and towns throughout the United States. Herded onto ocean liners, they disembarked in New York City, hundreds at a time, and then, if they were lucky, their husbands met them and took them to their new home.

Within 11 months, 30 ships carried 100,000 European war brides to the United States. Many led happy and fulfilling lives. But sometimes husbands didn’t show up in New York and their war brides had to take the return voyage. Sometimes that handsome GI in uniform turned out to be a drunk who lived in an unpainted shack and the marriage didn’t last.

The military did its best to discourage wartime marriages. The brass thought fraternization would result in the spread of venereal disease, undermine discipline and cause bad PR if too many GIs abandoned their wives and babies.

But the military was fighting a losing battle. Millions of GIs, mostly young, single men, served for an average of 33 months in Europe, Africa and Asia. Love, marriage and war brides needing transportation were the inevitable outcome.

World War I Brides

The U.S. military had struggled with the problem of war brides during World War I. Though the American Expeditionary Force tried mightily to prevent soldiers from having sex and dating local women, it failed miserably. According to one estimate, 71 percent of doughboys had sex, and 10,000 got married. Three-fifths married French women.

Gen. John Pershing realized the military had to do something to bring war brides to their new homes. To leave them stranded in Europe, many with newborns, would reflect badly on the American fighting forces. And so, the brides and their children were sent to camps, examined, processed and lectured. Then they boarded ocean liners and sailed to U.S. ports.

World War II War Brides

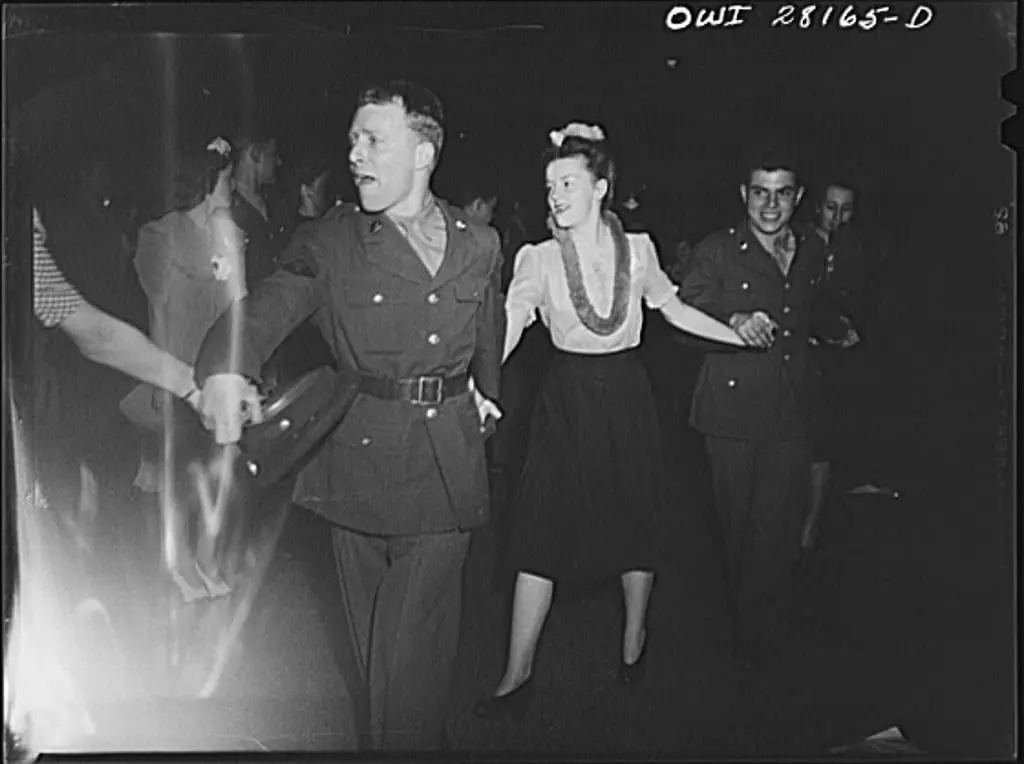

During World War II, the military first tried to prevent fraternizing just as it did in World War I. Newspapers and chaplains sermonized against getting involved with loose women. GIs stationed in Britain were given a 38-page handbook on getting along with the British people. The guide tried to dissuade the men from “special relationships” and especially marriage.

The U.S. War Department put obstacles in the way of wedding-bound GIs. A wartime regulation required overseas troops to get their commanding officer’s permission to wed. The groom-to-be had to fill out as many as 15 forms. It could take a couple a year to find out if they could or could not get married. At least one commanding officer refused to give permission to one GI, telling him to wait for an American girl.

Life Is Hard, America Is Rich

But American girls were an ocean away, and it was easy to meet local girls. Plus there were so many of them – an estimated four women for every man. War had decimated husband material.

Life was hard in Europe, and Americans were rich. The English endured bombings, blackouts and rationing, eight ounces of meat and four ounces of butter a week. The French lived through the German occupation and most of them went hungry. There was no coal for heating, no fabric for sewing clothes, no leather for shoes. Gas was rationed, and only pregnant women and babies got milk.

The average GI earned $50 a month, nearly five times the British soldier’s $12 monthly pay. The British girls used to say American soldiers were oversexed, overpaid and over here. {Americans replied the British were undersexed, underpaid and under Eisenhower.}

Jacqueline Olive, a Parisienne, met her husband Charles Xindaris while he was stationed with the U.S. Army in France. He stopped on a street in Paris and asked her for directions. They fell in love and married at Paris City Hall.

Ronald Clark saw the beautiful Nell Louisa while playing the piano at a serviceman’s club in England. Their whirlwind romance culminated in 65 years of marriage.

Red With Kisses

The French people viewed the GIs as liberators, and chic French girls showered them with hugs and kisses. They seemed friendlier than the German occupiers, giving out chewing gum and candy and playing with the children. After D-Day, Norman French welcomed them into their homes.

Because Marie Therese Mennechet spoke English, she was invited to a dance to honor the Allies who’d liberated her town, Quessy, from the Germans. There she met her future husband, Anthony J. Curcio. They soon married and she followed him to Hartford on a bride ship in 1946.

Some French women pursued American GIs. Amalio “Gio” Giovanniello, who belonged to Gen. George S. Patton’s 3rd Army, met Paulette Limousin during the liberation of France. His company knocked on the door of her family home and asked if they could use the roof as a lookout. Paulette wrote Gio hundreds of letters from then on. They reunited and married.

Other French girls were taught to say “Peut-être après la guerre.” (“Maybe after the War…”)

Many couples married after a courtship that lasted a few weeks or months. In the bloodiest conflict in human history, young men and women didn’t know if they’d be alive the next day – or the next hour. That, plus the extreme passions aroused by war thrust many young couples together quickly. Dating carried the risk that one of them wouldn’t make it. Sylvlia Bradley, who worked in a London department store, fell in love with a well-to-do Bostonian named Carl Russell. He was killed in the D-Day invasion.

What To Do With the War Brides

When the war ended on Sept. 2, 1945, the military’s priority was to bring the 8 million GIs and war workers home quickly from four continents. The Roosevelt Administration launched Operation Magic Carpet with the motto, “Home Alive By ’45.”

Where that left war brides was anyone’s guess. Could they even enter the United States without visas? They weren’t citizens, and Congress had set immigration quotas from foreign countries.

Many war brides hadn’t seen their new husbands in a year, and they were told it might be another year before they saw them again.

In London, 500 war brides visited the U.S. Embassy every day, wanting answers. When Eleanor Roosevelt visited London in November 1945, a mob of brides protested outside her hotel, carrying signs reading “We Demand Ships” and “We Want Our Dads.”

Frustration

Husbands were frustrated by the delays as well. In December 1945, an American sailor named Herbert Lamoureux jumped off the USS Argentina in Plymouth Sound. He tried to swim 5 miles in icy waters to shore to see his English wife, Veronica, and their new baby. He nearly died.

Lamoureux, an ex-sergeant, was being sent home, but his wife couldn’t find a way to join him. When he heard she was pregnant, he applied for a visa to return to England, but he was denied.

So Lamoureux signed on as a messman on Argentina, hoping it would dock in Liverpool, his wife’s home. When the vessel docked in Plymouth, he tried to get off by posing as a passenger. He failed, and so after the ocean liner left for Le Havre he dived overboard, fully dressed.

After nearly drowning he managed to climb onto rocks near a lighthouse. He shouted for help and another vessel rescued him. Ten house later, police deposited the “vehemently protesting” Lamoureux aboard another vessel returning to the United States.

By January, Eleanor Roosevelt reported in her newspaper column, “I think the end of the confusion is in sight.” The Army was making arrangements for the war brides to sail to the United States.

On Dec. 28, 1945, Congress passed the War Brides Act, which allowed foreign women, except Indians and southeast Asians, to enter the US as non-quota immigrants. The military paid for the newlyweds and their children to sail to their new homes aboard converted troop transports known as Bride Ships.

War Bride Camps

But first, British war brides were sent to the Tidworth Camp in Salisbury Plain for processing. One group was told, “You may not like the conditions here, but remember, no one asked you to come.” They slept in large, cold dormitories and ate meals prepared by surly German and Italian prisoners of war. They had to line up, take off their clothes and let a doctor shine a light between their legs. The war brides received lectures on life in the U.S. and instructions on travel.

Good Housekeeping magazine published a guide called “A Bride’s Guide to the U.S.A.” for British brides. It informed them that “apartment house” meant “block of flats,” “faucet” meant “tap,” “washcloth” meant “face flannel” and “drug store” meant “chemist.”

French war brides, along with some from other European countries, were sent to former army barracks called Bridal Camps. Staffed by the American Red Cross, YMCA, and YWCA, the camp secretaries were called Bridal Camp Commanders. The brides were processed, examined and instructed in American ways.

Most put up with it. In January, the SS Argentina set off with 452 war brides aboard, the first to take a group to the United States.

Hundreds at a time would disembark in New York to waiting husbands (they hoped) and news photographers.

In 1946, as many as 70,000 war brides arrived from the United Kingdom. Another 6,000 came from France.

Life in the USA

War brides weren’t always welcomed in their community. They carried stigmas, as adventuresses, carriers of venereal disease, threats to the American woman or gold diggers who got their claws into an American man to escape poverty-stricken Europe.

Americans frowned on French women after news photos showed French women kissing GIs when the 4th Armored Division drove into Paris. ”GI faces soon became red with lipstick,” the New York Herald Tribune had reported.

To cope with their strange new home, war brides formed War Bride Clubs. They helped each other find work and child care, consoled each other during bouts of homesickness and planned reunions in their home countries. The national War Brides Club estimates as many as 1 million war brides from 50 countries came to the United States between 1942 and 1952.

The Transatlantic Brides & Parents Association also formed to charter flights to take British war brides home to see their families. Still active throughout New England, it’s now open to anyone with British citizenship.

Happily Ever After

Jacqueline Olive, who met her husband when he asked directions in Paris, joined the local War Brides Club. She came to the States on the SS General George W. Goethals. The couple lived in Peabody, Mass., had two sons and worked together at Charles’ CPA firm in Salem.

Herbert Lamoureaux, the American sailor who jumped off the ocean liner to see his wife, ended up reuniting with her. They settled in Gardner, Mass., and had four more children.

Gio Giovanniello brought Paulette Limousin home to Brockton, Mass., where he became an architect who worked on the Jimmy Fund building. They had a long and happy marriage, a son, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Many of the GIs who brought home foreign wives were themselves immigrants or the sons of immigrants.

Luisa Mauriello met the love of her life, Carmen Solomito, in Naples. When the war ended, they married, and she followed Carmen to Waterbury, Conn. They had three children and brought the rest of her family to America.

Dina Filippi was born in Italy but grew up in Paris. During the war she got a job as a secretary for the French government. She met an airman of Italian descent, Albert Catanio, near Orly Airport. They dated for a year and got married in France. Shortly after Albert was shipped home, Dina took a bride ship with 300 other newlyweds to New York. She and Albert lived happily in East Greenwich, R.I., for 69 years with two daughters.

Not All Worked Out

Some of the war brides were penniless and married soldiers who couldn’t afford to support them once they landed in America.

Sometimes the marriages just didn’t work out. In those cases, the war brides often didn’t come to the United States. Their husbands didn’t think they needed to support them.

Victor Mahair’s wife complained from England that she hadn’t heard from him since he’d returned to the United States six months after their marriage. Consular officials tracked him down in New Hampshire. He said he’d sent her money to join him, but she said she couldn’t leave her mother and sister. Mahair was Catholic and didn’t want a divorce, but he wouldn’t support her if she wouldn’t live with him.

One Happy Ending

The war forced Trix Whalen to give up her competitive swimming career, but she found it again in America.

As a young teenager, Beatrice Wolstenholme swam for England’s national team and won four gold medals at the Irish Taliteann Games and a bronze in the European Games. At 12 years old she qualified for the 1932 Olympics, but she was considered too young to participate.

She married Sgt. William H. Whalen at St. Cuthbert’s Church in Withington, England, in 1945. They made their home in New Bedford, Mass., where they had five children. She still swam, though, winning medals in New Bedford’s annual long-distance free-style swim events, beating out much younger male competitors.

She also ran the aquatics program and taught swimming at the YWCA for 25 years, where she belonged to the War Brides Club. Her former students often recognized her in the grocery store.

“It’s all to do with life, that. Isn’t it? It’s about unknown possibilities. Goals. Perseverance,” she told the Standard Times in 2002.

Images: S.S. Argentina By Boston Public Library Fred J Hoertz & Harry H Baumann – The Good Neighbor liners Argentina and Brazil, operated by Moore-McCormack Lines, sailing from New York to the East Coast of South America, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26243707

Bibb: Babcock, Robert O, Gary W Swanson, George R Bibb, and Inc Americans Remembered. George R. Bibb Collection. 1942. Personal Narrative. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2001001.05683/.Tidworth

Lucknow Barracks By Andrew Smith, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13009048.